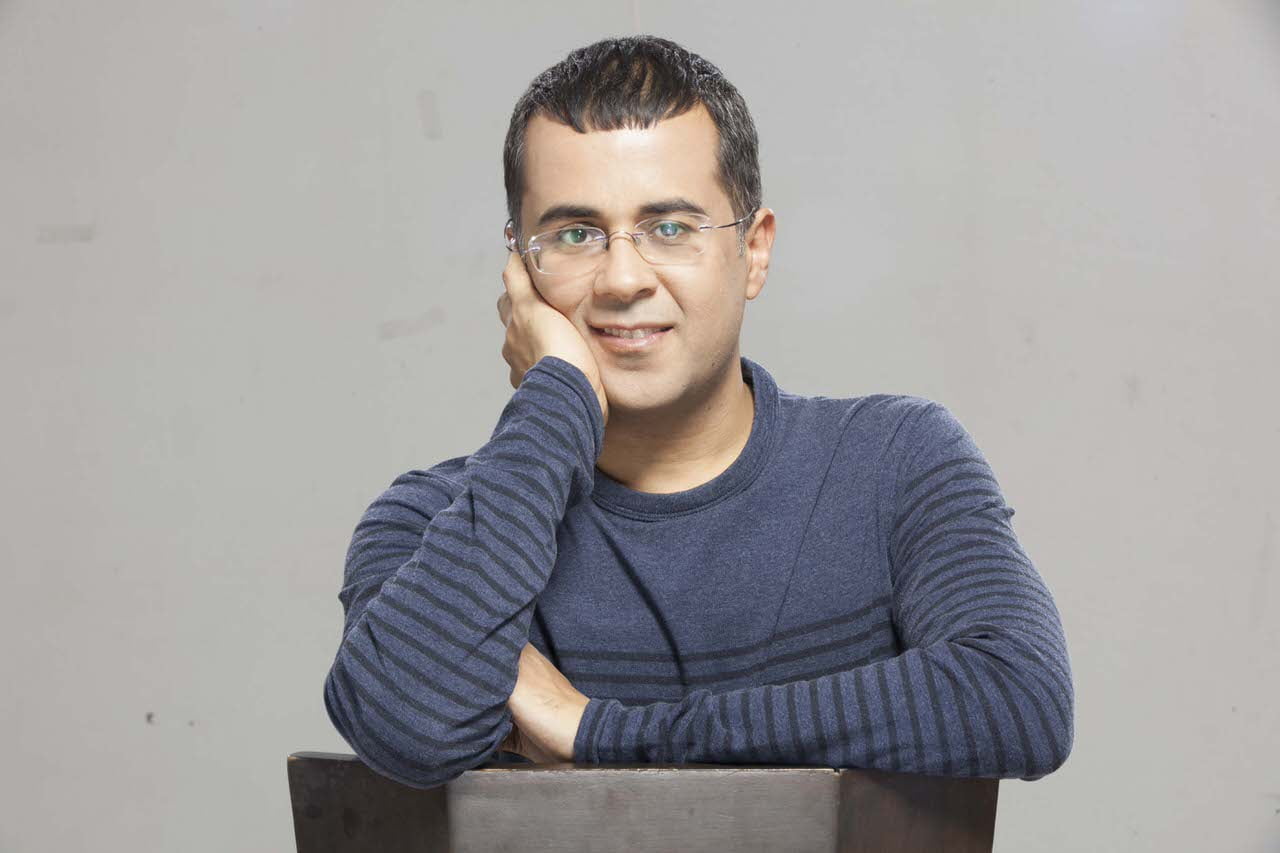

The inclusion of Chetan Bhagat’s Five Point Someone in Delhi University’s English (Hons) syllabus has invited a lot of discussion. Bhagat’s text is being included in the Popular Literature section along with the authors like Agatha Christie, Louisa May Alcott and J.K Rowling. While critics have called Bhagat’s writing “crass”, the author himself has repeatedly hit back at the bunch he calls “Elitistaan” or the literary/social elites.

DU including Chetan Bhagat's novel in its curriculum is like Grammy giving away a lifetime achievement award to Altaf Raja.

— Sudipto (@SudiptoDoc) April 25, 2017

Elitistaan theories trying to diss me and literary value of my books have failed miserably with DU adding my books to their course. Sorry.

— Chetan Bhagat (@chetan_bhagat) April 23, 2017

I think that the inclusion of Chetan Bhagat in DU’s syllabus is a positive move. While travelling in trains and buses, one strikes conversations with people who proudly say that they have read authors like Chetan Bhagat, Ravinder Singh, Durjoy Dutta etc. before moving on the other names.

His is the language, however “simplistic” and “crass”, which is understood by the majority of potential-readers in India that “literary” texts failed to attract.

Chetan Bhagat’s novels are a treat for the first time readers who may or may not be very comfortable with English. Bhagat is responsible for creating these first generation readers who have not grown up in an environment that encourages reading or literary pursuits.

His is the language, however “simplistic” and “crass”, which is understood by the majority of potential-readers in India that “literary” texts failed to attract. Bhagat and his “low-end” books are responsible for creating a space for everyone in the Indian literary scene. These were low-priced books that were relatable and made immediate contextual sense to people. Most of his preliminary readers to whom I have talked to say that they have graduated to other authors as their ‘first read’ encouraged them to read even more. As a Literature student, I know in some ways that reading is akin to thinking and this is not a bad start.

These authors have inculcated a reading habit in a public which doesn’t read anything except newspapers, stickers on the groceries, bills etc. Their writing provides a base for strong sense of identification that comes from the intimate act of reading. That is why the contexts Bhagat writes about are important. Novels like Five Point Someone, Two States, Three Mistakes Of My Life, One Night At A Call Centre etc. are either set in aspirational blocks like IIT and IIMs where the population wishes to go or in places where most of the “young India” belongs.

At his best, Bhagat has given us identifiable, recognizable, vulnerable male characters. At his worst, he appropriates and gives voice to his heroines using the same prejudiced lens.

The voices in Bhagat’s novels are predominantly North Indian male with all his associated prejudices, but also with his vulnerability, even if it speaks through female characters. At his best, Bhagat has given us identifiable, recognizable, vulnerable male characters. At his worst, he appropriates and gives voice to his heroines using the same prejudiced lens.

Mr. Bhagat may abuse the “Elitistaan”, but some of the accusations of the critics do stand. He tries to fit in the spirit of the age by making his women characters independent and outspoken, but in the end they collapse into being trophy women to be won by competing males.

Other sets of problems with Bhagat can be seen if one goes through his interviews and Twitter posts. His immensely naïve politics over building a Ram Mandir (forgetting the history of hate that continues even now), getting waxed (because this is, of course, the defining feminine experience) as a part of the research for writing a novel from a woman’s perspective (now with plagiarism accusations), and using “rape” lightly are few of the gems that Bhagat-enthusiasts ignore.

While discussing his novel Half Girlfriend he defends the non-English type men who have to be satisfied with ‘just being friends’ or ‘half-boyfriends’ of their respective crushes, due to the lack of their fluency in English. However, he never questions his fascination with the English-speaking fair-skinned woman. This is something that is taken for granted. Next, “deti hai to de, varna kat le”, the offending line in Half Girlfriend that was criticized for being in Hindi, is hardly a model for consent. This is also something that Bhagat-enthusiasts will ignore while discussing “plebeian voices”. Women serve as trophies that represent class-aspiration for these men either by being “beautiful”, rich or speaking English. And Biharis don’t English at all, no?

If Bhagat wanted to criticize nepotism and the tyranny of the English-speaking elite here, he does it badly. Or rather, he does it like any other “woke plebeian/middle-class” male who complains about being friend-zoned all the time, i.e., with no real self-reflexivity at all. He has the “good intentions” of discussing status quo, nepotism and unrequited love but does it in a classic fashion by aiming to antagonize everyone against the woman who rejects a man who “loves her so much”.

Women serve as trophies that represent class-aspiration for these men either by being “beautiful”, rich or speaking English.

All in all, we have seen why Bhagat appeals to these masses. It is because he talks to us in our own language. For the newly reading public, this is a much needed novelty.

Inclusion of his novel in Delhi University’s syllabus would prove fruitful to this reading consciousness. It would enable students to analyze the characters that one can see, touch, feel in our lives without putting much thought. The protagonists and the characters of Bhagat’s fiction don’t exist inside his text, rather they exist outside in our every day. The students, across disciplines, should analyze the readership more than his texts because it is an accurate, if not acceptable, description of how things are seen, talked about and accepted.

He has “good intentions” of discussing status quo, nepotism and unrequited love but does it in the classic fashion of antagonizing everyone against the woman who rejects a man who “loves her so much”.

Taking cue from Mr. Bhagat’s aesthetics – Beware against the “Elistaan/I hate Bhagat” types and the “All hail Bhagat who sold a million copies” types. One can hope that teaching and studying Bhagat in classrooms allows students and teachers to ask and engage with difficult questions and representations that form a part of our daily code of conduct. If done properly, there couldn’t be a better mode of introspection.

About the author(s)

Richa Thakur is a literature student who reads people and books wherever she goes. Researcher and experimenter by technique, she is currently concocting formulas to fight all kinds of patriarchy.