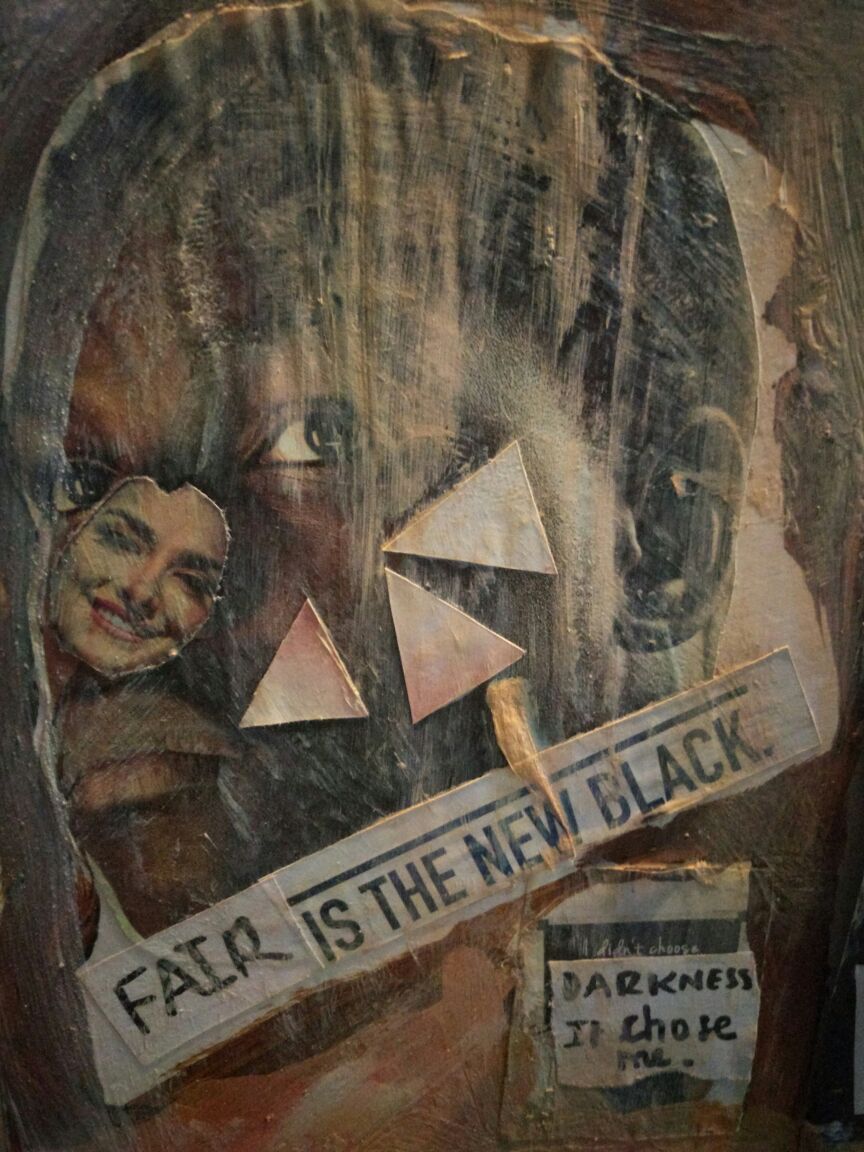

Mounted on the wall as soon as you enter the exhibition is a canvas with fragmented images from glossy magazines and newspapers. Painted all over them is the colour I recognise only too well. It is that distinctively creamy, light brown colour that was part of every crayon and paint set I used as a child – ‘skin’ colour – the homogenous shade that defines a spectrum.

Something seemingly superficial that runs very deep, psychologically and socially. It is the intersections of skin colour, race, caste and ideology that forms the central theme of ‘Battling to Normalise Freedom’, an art exhibition being showcased by the Clark House Initiative in Mumbai.

It brings together the works of three artists from three countries – Amol Patil (India), Aissatou Diop (Senegal) and Saleh Lo (Mauritania). Curated by Senegalese curator Marie Helene Pereira, the exhibition borrows its name from the South African writer Pumla Dineo Gqola’s book Reflecting Rogue: inside the mind of a feminist.

An image from Amol Patil’s exhibit

In her video that explores what goes behind Senegalese women choosing to depigment their skin, Aissatou starts off by talking about a boy. “He had blue eyes, blonde hair and a pale complexion…and I loved him“. She clarifies that she doesn’t know why she loves him.

But if she changes the syntax to say what the sentence really means she would say “I loved him BECAUSE he had blue eyes, blonde hair and a pale complexion“. Her video goes on to depict candid interviews with 21 young children, 15 of whom say that they prefer the white doll to the black one.

When asked which doll is pretty, which one is nice, they point to the white doll. When asked which one is bad, which one is ugly, which one looks like you, they point to the black one. How do you reconcile yourself to being the ugly, bad doll?

Through the course of her video, Aissatou examines that question. She isn’t subtle and she doesn’t tread lightly. She says exactly what she wants to say, loudly and explicitly, both through her narration and images.

An image from Amol Patil’s exhibit.

Towards the beginning of her video, there is a harrowing image of a boy sitting with his white doll and watching something on television. I can’t quite recall what the image was but it could have been anything, from the Senegalese equivalent of a Bollywood song where young women boast about having ‘chittiyan kalaiyan‘(white wrists) to the fairness cream ad that equates a woman’s professional success with her complexion.

In another segment of the video when a middle-aged woman watching television comments on someone saying ‘she has a very beautiful skin colour’, I immediately recall at least ten instances of similar comments by women I know. In the cutouts of magazines from which Amol has purposely ripped out the faces, I see myself, applying honey and neem powder every morning for ‘clear’ and ‘glowing’ skin.

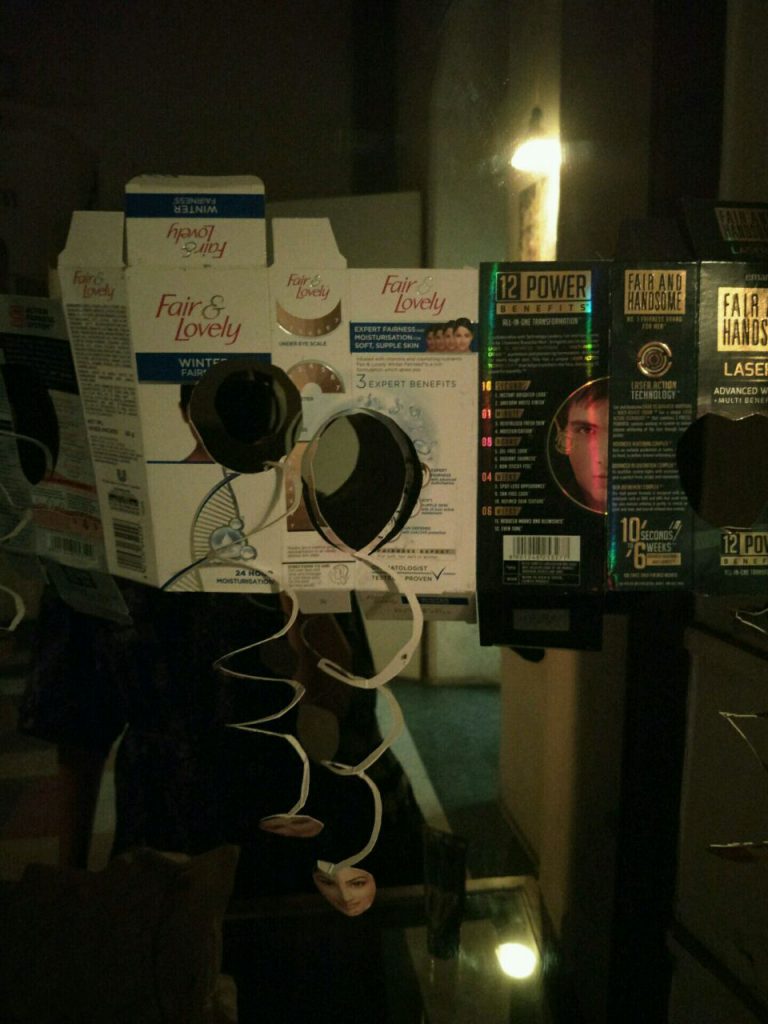

Amol’s images depict Indian society’s obsession with ‘fair’ skin, best represented through the pages of ‘glamourous’ magazines.

There is a moment in Aissatou’s video when the camera zooms in on the smooth, white bleach mixture, and for a good thirty seconds, all you can see is the whiteness of it. It is a compelling image that resounds with the words Amol has chosen to put up as part of his installation on the idealisation of fairness in Indian society- ‘Beautiful is Powerful’, ‘Packed to Perfection’, ‘Big Day Beauty’, among others.

Aissatou goes on to explore the dangerous physical consequences that the need for fairness has on women’s skin due to over-bleaching. The use of these products becomes like a drug addiction, she says.

Similarly, Amol’s images depict Indian society’s addiction to/ obsession with ‘fair’ skin, best represented through the pages of ‘glamorous’ magazines that drive readers to be the ‘best’ physical versions of themselves, setting and reinforcing problematic beauty standards.

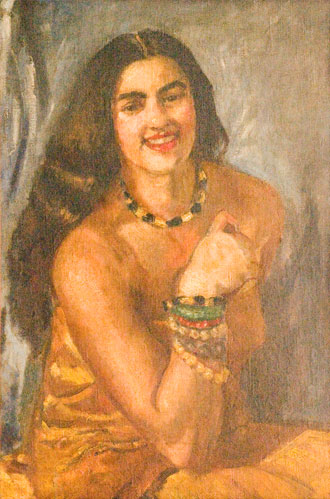

Oil on canvas of an activist protesting in Mauritania by Saleh Lo

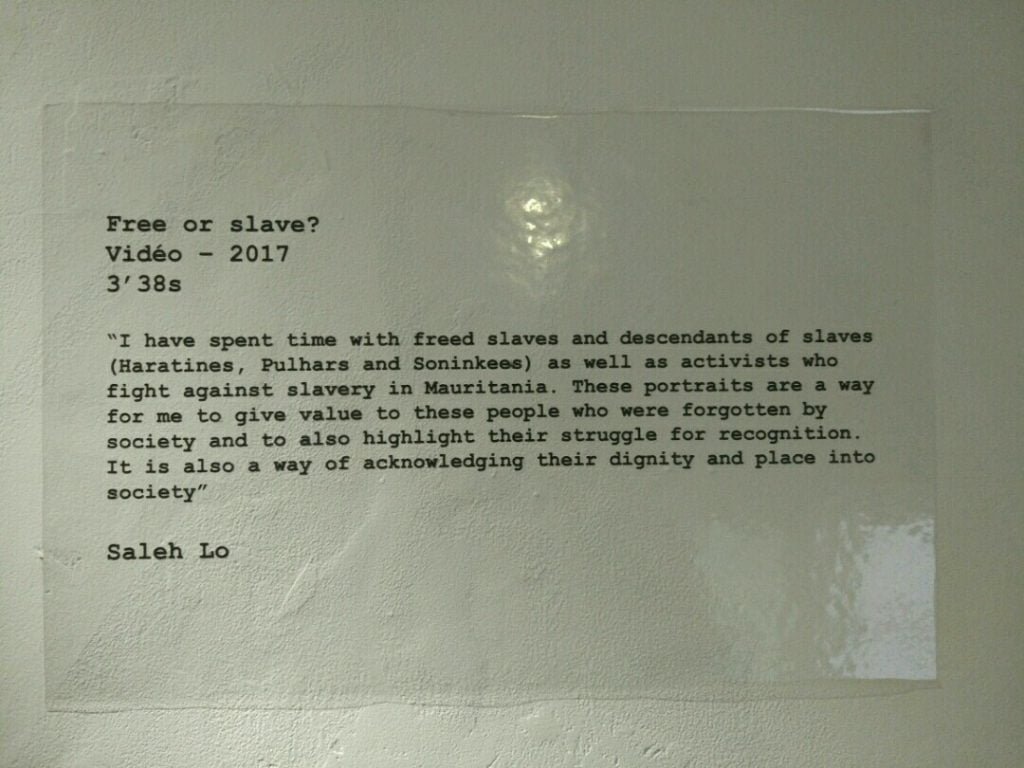

And then there is the work of Saleh Lo that deals with the harsh reality of the enslaved community of Mauritania, where the continued existence of slavery contributes to reinforcing racial discrimination. Saleh has painted oil on canvas portraits of many recently freed slaves, some of whom have been freed as recently as 2009.

Saleh has been working closely with freed slaves and activists. He sees his portraits as a means of giving value to people who have been forgotten by society, highlighting their struggle for recognition.

While the first few images are staid portraits, the others depict activists in action, speaking out and fighting for their rights. A few of these portraits are incomplete. Saleh clarifies that he was unable to finish the paintings because of the severity of the conflict.

Effectively tying together stories from three countries, this exhibition made me acutely aware of the violence I inflict on my skin (and myself) and the role I play in projecting that violence outwards as a ‘fair-skinned’ savarna woman. Saleh’s unfinished portraits become emblematic of a larger battle that continues, here and elsewhere, within and without.

This art exhibition is on until 28th January 2018. It is a collaboration between RAW Material Company, Dakar and Clark House Initiative. It is being exhibited by the Clark House Initiative in Mumbai. The initiative was set up in October 2015 as a curatorial collaborative concerned with ideas of freedom. For the venue, timings and other details, check out their Facebook page.

Also Read: Reviewing The Riot Grrrl Collection: Feminist Movement From The 90s

About the author(s)

Shrishti is a student of Media and Cultural Studies. Long rants with female friends help her channelize rage on the world around. Good food, pretentious poetry and cute canines provide her endless pleasure.