Editor’s Note: #ChalkfullBullying is a campaign that resolves to tell stories about gender-based bullying that happens in school, where students, especially non-binary and girl students, are subject to harassment, moral policing, severe disciplining and punishment, and routine bullying. Their fault being: not conforming to outdated gender stereotypes, the repercussions for which can scar us for a lifetime.

When I hear about school students speaking up forcefully against sexism in dress codes, I feel a twinge of guilt along with pride. You see, I was complicit in the bullying – especially when it involved bullying the attractive, popular girls, who I so desperately wanted to relate to.

Ever since moving to North India in the fifth grade, I was almost always the odd kid out growing up. Schoolwork was a breeze for me, but I had trouble understanding the nuances of what defined the term ‘cool’, which seemed to govern most social interactions.

I did weird things with my body. I had strange tics – I suspect looking back that it was some form of stimming and I may not be neurotypical. I did not speak Hindi as well as English and I was far more interested in editing Wikipedia than hanging out on Facebook.

I remember being singled out and made fun of for all these things. I did have friends, but apart from a few, most were willing to ditch me in order to up their social image. I, in turn, was mean to those who were nice to me but weren’t ‘cool’ enough. After all, I also didn’t want to be made fun of for sitting next to the kid with “Maggi hair”.

I had trouble understanding what defined the term ‘cool’, which seemed to govern most social interactions.

I retaliated by seeking out approval from authority figures. This was easy enough – my grades were good enough for most teachers to like me. All that I needed, in addition, was to be compliant with their bullshit – which I was, because I shared many of their views.

My first school in North India was a Christian school. Apart from making us sing Christian prayer songs for an hour a day, our teachers drilled ‘good values’ into us by making sure our skirts ended below our knees and our socks were pulled up mid-calf.

The popular girls got their skirts tailored so they ended just above the knees and pulled down their socks until they were ankle-length. I didn’t really appreciate them violating discipline, but I thought they looked cute – even though they were made to stay back after the assembly and run two rounds of the field as punishment.

After many days of enviously looking at them, I decided to imitate them, hoping I could fit in better. I tried multiple times to convince my grandmother to hem my skirt to make it shorter, but she refused (“It’s better this way, people won’t see the ugly spots on your legs”). I decided to try rolling down my socks like the other girls to make them look like cute little ankle socks. But I didn’t know how it was done and it just looked shabby on me. Besides, people would stare at my spots.

All through eighth grade, when our hormones were beginning to show and our first crushes were becoming our first relationships, I remained frumpy and unattractive in my glasses-braces-oversized clothes. I’ve lost count of the number of “fake proposals” that boys made to me because apparently people being attracted to me was nothing less than a joke.

In the ninth grade, to my relief, I was selected to join the school council. I was given the utterly useless post of ‘Science Minister’ (“taking care of the science lab and spreading scientific temperament among students”).

But that didn’t matter – my real duty was to pull out ‘defaulters’ with long nails, hair done the ‘wrong’ way and – you guessed it – short skirts. Of course, I couldn’t do much to my batch mates – I was frightened of retaliation – but I took out my frustration on junior girls, whom I would pull out gleefully and watch them mope all the way to the back of the line.

Two years later, I moved to a new, secular, well-known school for better prospects. I still remember how well that interview went: me, smiling, declaring in front of my parents: “I am a feminist”. My new principal, smiling broadly, responded, “Me too”.

Of course, both of us were lying, but I didn’t know that yet. I was impressed at how ‘liberal’ the new school was. Girls in eleventh and twelfth grade were allowed a little kajal and long nails because the principal thought they had the right to self-expression. We rarely had morning assemblies and the school council had actual jobs. The misogyny and gender-based policing, however, still persisted.

Also Read: Where’s The Prestige Now? St Anthony’s Students Speak Out | #ChalkfullBullying

Girls who came in casuals weren’t allowed to wear sleeveless clothing – even modest ones – without a shrug. I have vivid memories of boys being pulled out of class and forcibly being given horrible haircuts just because their hair was too long. I initially thought it was funny, of course – in any case, I thought they looked like idiots because of their hair.

But these instances happened rarely – perhaps once in three or four months if we were unlucky. Model UNs, however, were a different ballgame. Surprisingly, our new school had much more regressive attitudes towards them than my old Christian school.

Regardless of how strict my old school was with their uniform, it was understood that once the uniform was off, you could wear anything you wanted. The faculty who accompanied us to Model UNs cared more about whether we won our little-known school awards. In my new school, however, our social capital ensured that at least a few awards were always rigged in our favour, so the administration – our loving principal, in particular – could bother about other things.

As I was in a new school, I had upped the stakes by buying new, attractive formal clothes for my first internal MUN, which is what would establish my place in the school. They included stylish new pencil skirts and a lovely grey dress – all of which made me feel like the powerful Delegate of China that I was supposed to represent. Imagine my shock when, on the second day of the Model UN, all the female delegates were called from their committees and asked to assemble in the auditorium.

I retaliated by seeking out approval from authority figures.

The faculty member walked around all sixty of us, inspecting the length of our skirts individually. Only those whose skirts fell below the knees – such as ‘good girls’ like me – were allowed to sit. We were all lectured on discipline before being allowed to return to the competition, by which time the male delegates had already moved forward in the discussion.

On the third and final day, I wore my grey dress, which made me feel so powerful. (“Delegate of China, Tigress in the making”, I called myself.) I remember I was in the middle of shooting down the Delegate of USA’s point when the faculty advisor walked in. “Who has dared to wear skirts even after my warning yesterday?”

Silence.

I stood up, confused. I must have been in the okay, right? My skirt fell to my knees. I timidly said as much. She walked up to me, and, in front of an entire committee of mostly-male delegates, she measured the length of my skirt. When she left, the relevance of my point had been lost. The delegate of the most powerful economy in the world was trembling with shame.

Looking back, I find it surprising that even personally experiencing sexist humiliation didn’t do much to change my views on the suitability of certain clothing. Following these incidents, we weren’t allowed to wear dresses or skirts to external MUNs and I didn’t sympathize with the other female delegates ‘whining’ about such a ‘trivial’ problem. In fact, the next year, when I applied to run the Model UN, I was asked how I would respond to a female delegate who came in wearing a skirt. My response? “I’d send her back and ask her to change. Rules are rules.”

One of my new friends, who vehemently disagreed with me, worked very hard to change my mind. Although I was initially reactive, I did begin to see more and more how hurtful my behaviour was. When our loving, ‘feminist’, role-model principal publicly shamed another student for being sexually harassed, I finally caved and spoke out against her to my teachers.

She walked up to me, and, in front of an entire committee of mostly-male delegates, she measured the length of my skirt.

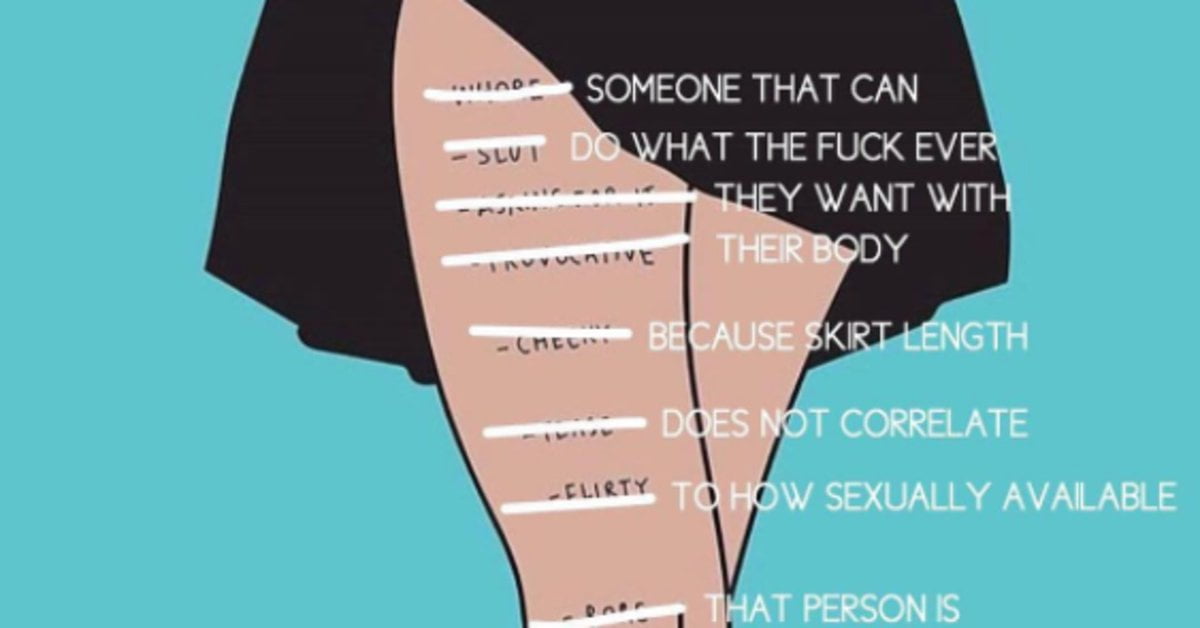

My principal and I began our mutual dislike shortly thereafter, for this and a host of other reasons, which only ended (from her side, that is) when I topped my boards and entrance exams. Although I disliked her, I still carried several of her misogynistic ideas about clothes with me. It took me a year of college and lots of conscious effort to finally stop judging girls and women for wearing revealing clothing – a right which I had outwardly advocated much before while inwardly struggling to not call them ‘sluts’.

If I were to be completely fair to myself, going up against authority figures is a lot harder when you are younger. This is especially true if, like with me, their approval is the only thing that is holding your fragile self-esteem in place. But I didn’t even try, because I saw their attacks as something which only targeted the ‘pretty, popular’ girls – the same girls who I believed were always laughing at me.

While I can’t undo the damage that I have done to other girls due to my internalised misogyny, I do plan to have my future children – and all other children who will be a part of my life – grow up to be better human beings than I was. I want them to be non-judgmental of people’s clothing choices and I want them to be able to stand up for what’s wrong – even if it’s happening to someone they don’t necessarily like.

Above all, I want them to know that just because an adult is saying something, that doesn’t make it true or right – even if the adult is me.

Also Read: My School Was A Breeding Ground For Humiliation | #ChalkfullBullying

Featured Image Source: Scoopnest

Thank you so much for writing this article and bringing this to light. In my school too, when going for MUNs we were told to try and wear only trousers and no sleeveless, and that if we did have to wear a skirt or dress to wear stockings and they would have to be below the knee.

Despite following all these rules, my friend was shamed because they felt her dress was “inappropriate” (it was a lovely button up black dress that did adhere to their rules – it was below the knee and she did wear stockings) but they forced her to borrow clothes and change right before leaving and humiliated and hurt her by mentioning her parents too.

The next year, they banned skirts and dresses completely. My friend and I, unaware of this, turned up in dresses and we were scolded too. I’m ashamed to say that we didn’t fight back much – we were scared of the teachers and when we did organise an MUN the next year, we managed to ensure the teachers wouldn’t punish those from other schools but we ourselves just quietly wore trousers and sleeved blouses because we knew what would happen if we didn’t.

I’m sad that I stayed silent then but next time when this happens to someone else, I’m going to speak up, and this is thanks to all of you who write these articles and give us courage. Thank you for speaking out and inspiring others to.