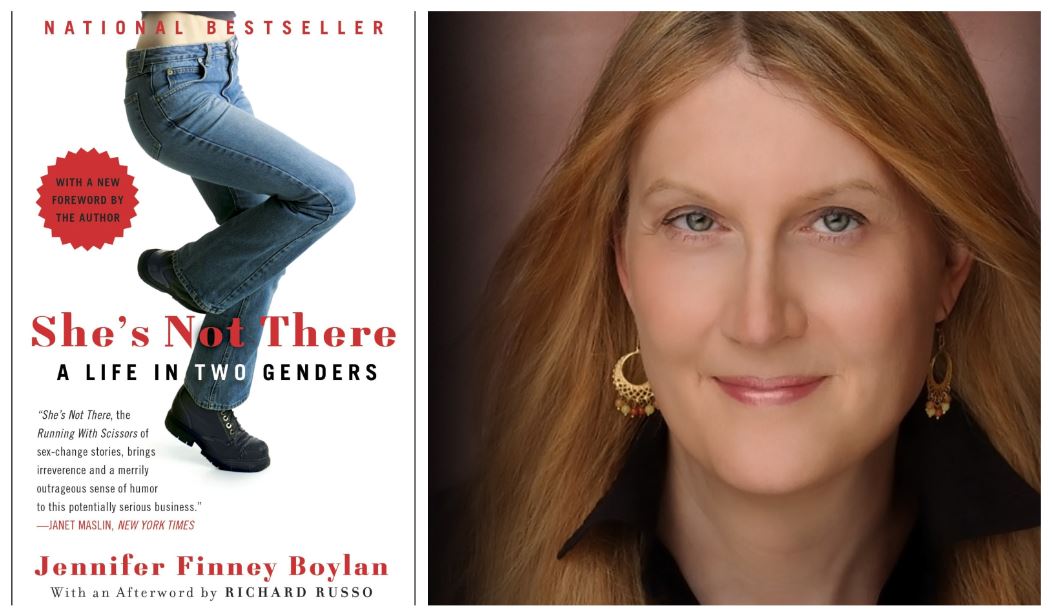

She’s Not There is the bestselling memoir by Jennifer Finney Boylan on a “life in two genders.” It’s a funny and evocative account of the severe experience of being caught in the wrong body, and the journey to the right one. Jenny – née James – is a successful writer, head of the English Department at Colby College. James is very privileged. It is important to keep sight of this through the book, for there are hundreds and thousands of trans folks without support, safe spaces, and privileges struggle in their persecution. James is bestfriends with Richard Russo(Rick) and he has a saint-like partner, Grace, with whom he has two children, and a Rock and Roll band. He has everything – except something’s not right.

One of Boylan’s strongest achievements is how she describes the experience of holding a massive, existential secret – its weight, its constant presence. Jenny is trying to live her life as a man, hoping love will ‘save’ her – that is, hoping that her marriage to Grace will overwhelm her desire to wear skirts and her grandmother’s gaudy earrings. But her gender dilemma is so much more than those earrings, and so nothing diminishes its weight. Not even the children who run to greet her at the door crying “daddy’s home!” Because, as Boylan puts it, “in the end, what [being transgender] is, more than anything else, is a fact.” This is her credo, and well before the end, it’s yours too.

Jenny is trying to live her life as a man, hoping love will ‘save’ her.

Boylan makes the reader ponder the factual nature of ‘femininity’ and ‘womanhood’ – what it’s like to wake up in the morning knowing that you are a woman. For example, she writes evocatively about when she was a boy of three, watching her mother ironing her father’s shirts. Her mother holds one up and says to James, “Someday you’ll wear shirts like this.” James is nonplussed; he cannot understand why he would wear shirts like his father’s when they are nothing like the ones his mother wore. Anecdotes like this – and the book as a whole is peppered with them – perfectly encapsulate this knowledge that most of us take for granted. While I have (like many others) wondered what it would be like to be a boy, I never felt like my body was wrong. That, as a matter of fact, it needed to be a boy’s body.

Jennifer begins the journey physically transitioning into a female after confiding in her wife and taking time to live en femme. Once her transition is in its advanced stages, and Boylan can finally start living as Jennifer, she experiences womanhood with a body that finally mirrors who she really is. Here’s where some of her anecdotes lose their power. For example, she writes about choosing a pair of jeans. As a man, she made the decision easily. As a woman, she considers buying a size or two smaller, thinking that she may one day fit into it. This foreign thought catches her by surprise. It surprises the reader. We struggle to understand the origins of this body inadequacy, especially since we see no indication of her being weight-conscious as a man.

Women growing up in female bodies are all too familiar with the decades of near-constant brainwashing – by families, advertisements, and social media. In Hunger, Roxane Gay writes about the weight loss industry, “What does it say about our culture that the desire for weight loss is considered a default feature of womanhood.” Asking how Jennifer perceived and internalised these social standards, and how they fit into the experience of womanhood would have made an insightful discussion, but she leaves this unexplored.

Once her transition is in its advanced stages, and Boylan can finally start living as Jennifer, she experiences womanhood with a body that mirrors who she really is.

Jennifer’s transition comes at a tremendous cost to Grace – her husband. This is the most complex relationship in the book, but it leaves many questions unanswered. Throughout the transition, Grace has sporadic breakdowns that apparently have no bearing on the course of events.

She cries many times, worried about how ‘near’ they will remain after the transition, telling Jennifer honestly that this wasn’t what she signed up for, feeling like she is lost and betrayed – all the while giving Jenny her blessing to go ahead with her decision – because she fundamentally gets that no one has the right to make Jennifer’s choices about her body and personhood. But we are left with the unsettling possibility that nothing Grace said really mattered. The writer only offers clues about Grace’s feelings of bereavement – losing her husband – from the discussion she has with James about losing her father. That the pain dulls, but it never really goes away.

Also read: Is Gender Transition A Need Or A Wish?

Perhaps we are meant to recognise that happiness isn’t always unadulterated, that success comes with pain and sacrifice, that loss can accompany gain, that making peace with something requires struggle. Perhaps Jennifer is right in withholding so much of Grace from us – that’s Grace’s story, and when and how she chooses to tell it is her prerogative. The afterword includes a small piece penned by Grace ten years later (her real name is Deirdre) titled Imagining Grace, which offers some closure. But the fascinating fraught territory in which her feelings existed and her journey to acceptance are largely left untouched.

Another aspect of femininity that seems sanitised is Boylan’s treatment of female sexuality. Jennifer undergoes full gender reassignment surgery and is assured by the doctor that she will be ‘orgasmic’. At no point is the book heavy on sex, and so we don’t expect graphic details. We are lightly assured that she is, in fact, ‘orgasmic’ post-surgery, but that’s it. In the afterword Deirdre writes that she and Jennifer no longer have a sexual relationship, but we never fully know where Jenny is on the spectrum. I would argue that this wanting to know more isn’t gratuitous or voyeuristic as we need a way to comprehend different experiences of female sexuality.

Also read: A Queer Sikh Trans Man’s Story Of Transition And Community Formation

Ultimately, maybe love does change James. Grace’s love for Jennifer – regardless of who she was on the ‘outside’ – is so strong, that fifteen years after She’s Not There, they are still married. The love from her children, Rick, and her bandmates helped save her from living a falsehood. This book is required reading and a great starting point for a window into some of the realities of a trans woman’s life.

About the author(s)

Madhuri Sastry is the founder of the gender blog Chicks and Balances. She hols two LLMs, from the London School of Economics and New York University. Find Madhuri on Instagram @supportedfish and on Twitter @Chicks_Balances