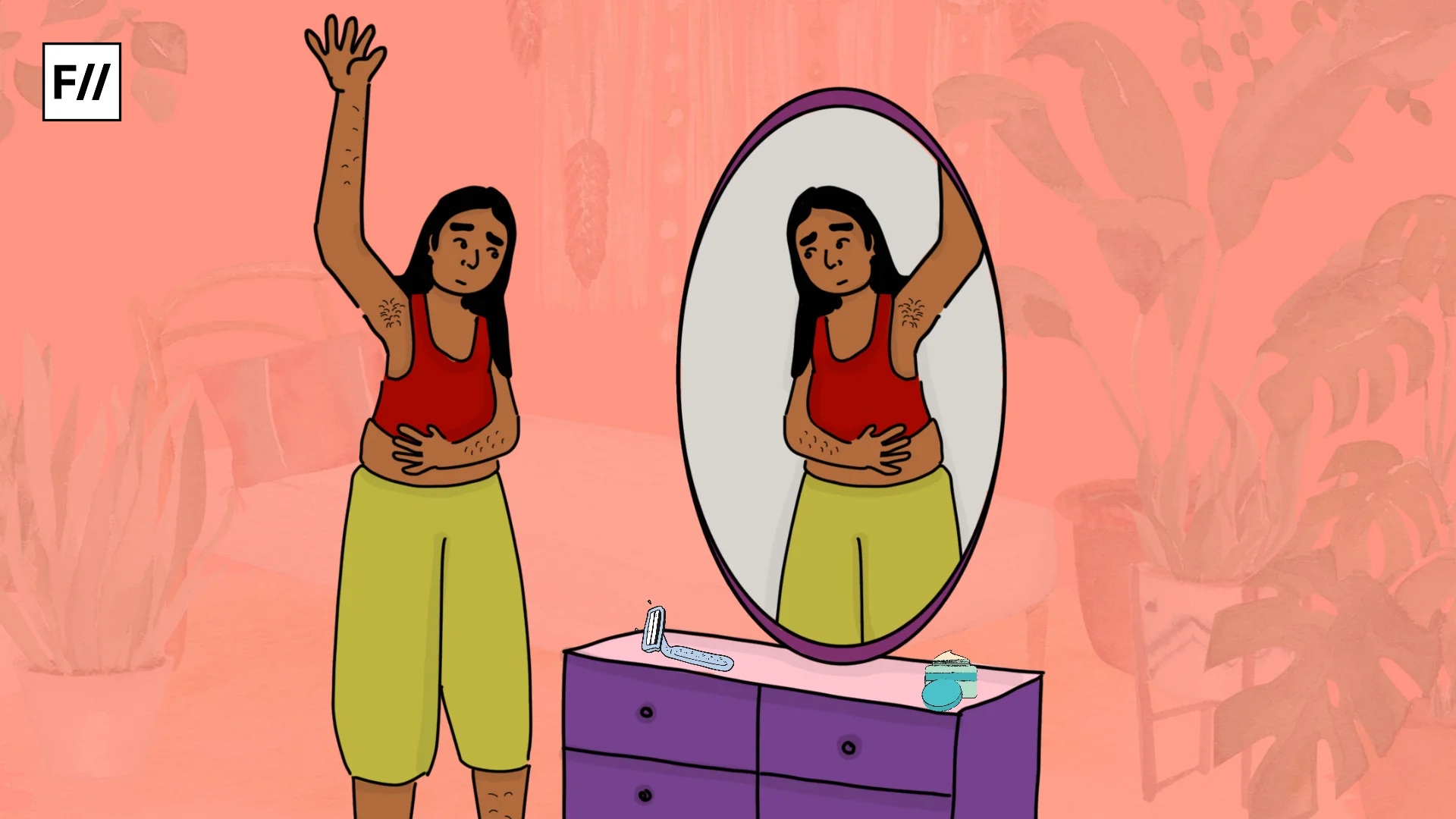

The standards of beauty in relation to South Asians have perpetually been problematic, especially for women. An unhealthy obsession for lighter skin tones and a distaste for darker skin tones is ingrained in South Asian culture. One may ask, what is it like for someone like me, who cannot easily be categorised into one particular colour column? If we equate being fair as being a plus and dark a minus, then surely someone who is both light and dark must be somewhere in the middle? The answer is no! Unfortunately, such a situation is not formulaic. Instead, a South Asian woman with vitiligo faces experiences of stigmatisation and as a result she needs to psycho-socially adjust accordingly.

At the age of 7, the symptoms of vitiligo initially started from the corner of my eye, then very quickly spread throughout my whole body. In the past 16 years the extent of the marks has fluctuated, however since the age of 7 I have never been of just one colour, but rather in between colour columns. Growing up in the UK as a Bengali Muslim Woman with vitiligo is as intersectional as I could ever imagine the lives of the other children I went to school with. Now, 16 years later I can reflect on how South Asian prescriptions of beauty not only shaped but also fragmented my sense of self, constantly succumbing to and subverting the discrete categories placed on my identity.

My parents were bombarded with unsolicited advice on various treatment options and told how it would be difficult for me to find a ‘suitable’ husband if my vitiligo was left untreated. According to South Asian standards it came down to two things: first that I was no longer the “pretty face” I once had pre-vitiligo and second “Who will marry a girl with vitiligo?”.

The desire to lighten one’s skin has long existed among South Asians, from traditional Ayurvedic beauty treatments to the vast market of fairness creams. Most womens beauty salons in South Asian countries have a huge proportion of treatments targeted at skin lightening. The need to conform to these standards have become such an issue that many are unbothered by the way in which the majority of these treatments have risks and can prove to be harmful in the future.

Also read: The Old-New Brand Of ‘Natural Beauty’ – Just As Hypocritical As The Makeup Industry!

External beauty has become a priority, all because of the emphasis placed on the same. I often get asked by makeup artists if I have special makeup to cover my marks, and my refusal is extremely shocking to them. Although this desire for fairness exists between both genders, it affects women by a disproportionately large scale. So, in a community so fixated on fairness, where does a woman with vitiligo stand? Well the answer is, she doesn’t. She is always seen as the ‘other’ and is marginalised to the extent where she needs to look for ways to conceal the ‘flaw’.

In popular culture, most if not all of the ‘quintessential’ tv and film heroines are fair or become fair. This notion of fairness is associated with beauty to the extent where our conception of the real is distorted. In reality most people in South Asia do not have access to dermatologists or beauticians. The regular person may suffer from skin problems like acne, eczema or vitiligo, which is neither represented or reflected on-screen.

In the Bollywood movie Satyam Shivam Sundaram, Roopa is essentially disregarded by her husband for a part of her face being burnt, however the hypocrisy of society is seen through her husbands obsession with the ‘beautiful side’ of her face. Her veil is her mode of adjustment against the stigma but it also leads to the fragmentation of her self; she is simultaneously seen as beautiful and damned. In South Asia a woman’s body and how it is presented is the site of immense scrutiny and often their personality or character is determined by it.

I often get asked by makeup artists if I have special makeup to cover my marks, and my refusal is extremely shocking to them.

In my experience, vitiligo affected my hair alongside my skin, as the loss of pigmentation spread to my scalp, causing my hair to turn white. Throughout my teens I hid behind conservative clothing and the hijab, using my Muslim identity as justification when in reality I wanted to hide the extent of my vitiligo. Almost everyone thought that I was a super-religious Muslim girl, but the choice to wear clothing that covered my marks was not at all religious but a tool to prevent humiliation. This humiliation is inbuilt and a result of the obsession with beauty that was imposed upon me by those around me.

Through all this, although one’s parents may be supportive, the overall stigmatisation imposed by society did not adhere to building my self-esteem. Experiences of stigmatisation made me realise that my own self-acceptance of having vitiligo and being somewhat at ease in my own skin will never be fulfilling unless society as a whole does not embody this acceptance. Through the lens of this society obsessed with external beauty who see me as the ‘other’, I will always feel like the ‘other’.

Apart from this fixation with fairness, there is also an obsession regarding marriage, which is almost always restrictive for women. As I was reminded many times by random relatives, I needed to take care of my skin so that I can find a nice husband. However, the same would not be said to a man with vitiligo.

At the age of 21, I was tricked into meeting a man who was more than a decade older than me by some relatives, without my parents knowledge. I felt violated as I had simply gone to visit a relative and did not expect this imposition. This incident was an eye opener to how people saw me: my vitiligo could be and was being bargained for age. My position as a woman living in the UK allows me the privilege of saying no, however it frightens me to think of all the women who do not have the autonomy to do so.

I wish my 7-year-old self was told that she will be beautiful no matter what, instead of being marginalised for something she has no control over.

This reminds me of a girl I met in Bangladesh when I was a child who, despite being very beautiful was married off to a man significantly older than her father as both her eyes were not the same colour. Due to the poor economic situation of her family and the stigmatisation of not looking the same as everyone else, saying no was not an option for her. This incident only reinforces the pressure on women to conform to established beauty standards.

In an alternate universe where I did not have vitiligo the same relatives would have brought forward very different kinds of marriage proposals. I would not be put in such a situation, where I would have to bargain my flaws while a man’s flaws are overlooked and they are never required to lower their standards.

I wish my 7-year-old self was told that she will be beautiful no matter what, instead of being marginalised for something she has no control over. The first time anyone referred to my vitiligo as ‘beautiful’ was my year 10 art teacher Ms Maker, “a piece of art” she called it. This comment did not seem like a compliment, at the time it felt like a sarcastic comment. I could not comprehend how someone had called the feature most people found unattractive about me beautiful.

It took me many years to digest what my art teacher had said and many more years to recognise and deal with all the insecurities I had developed as a result of the constant indirect shaming for having vitiligo as if it is a choice.

Also read: Vitiligo In A Woman’s Body: How I Learnt To Survive A Patchy Situation

Now, for the past 3 years having recognised the perpetual imposition of beauty standards on women, I have very consciously stopped myself of any psychosocial adjustment. My clothing no longer strives to cover my vitiligo, I no longer adorn a hijab for the wrong reasons and most importantly I no longer feel less for not fitting into the typical conventions of a beautiful South Asian woman.

Featured Image: Filthy Disgusting

About the author(s)

Nikhat is a Civil Servant and Communications Manager for BBPC Poetry Collective. Her academic research interests include wartime gender-based violence and intersectional feminist historiography.

It actually is good to feel that someone raised this issue..We need to change the mind set of society