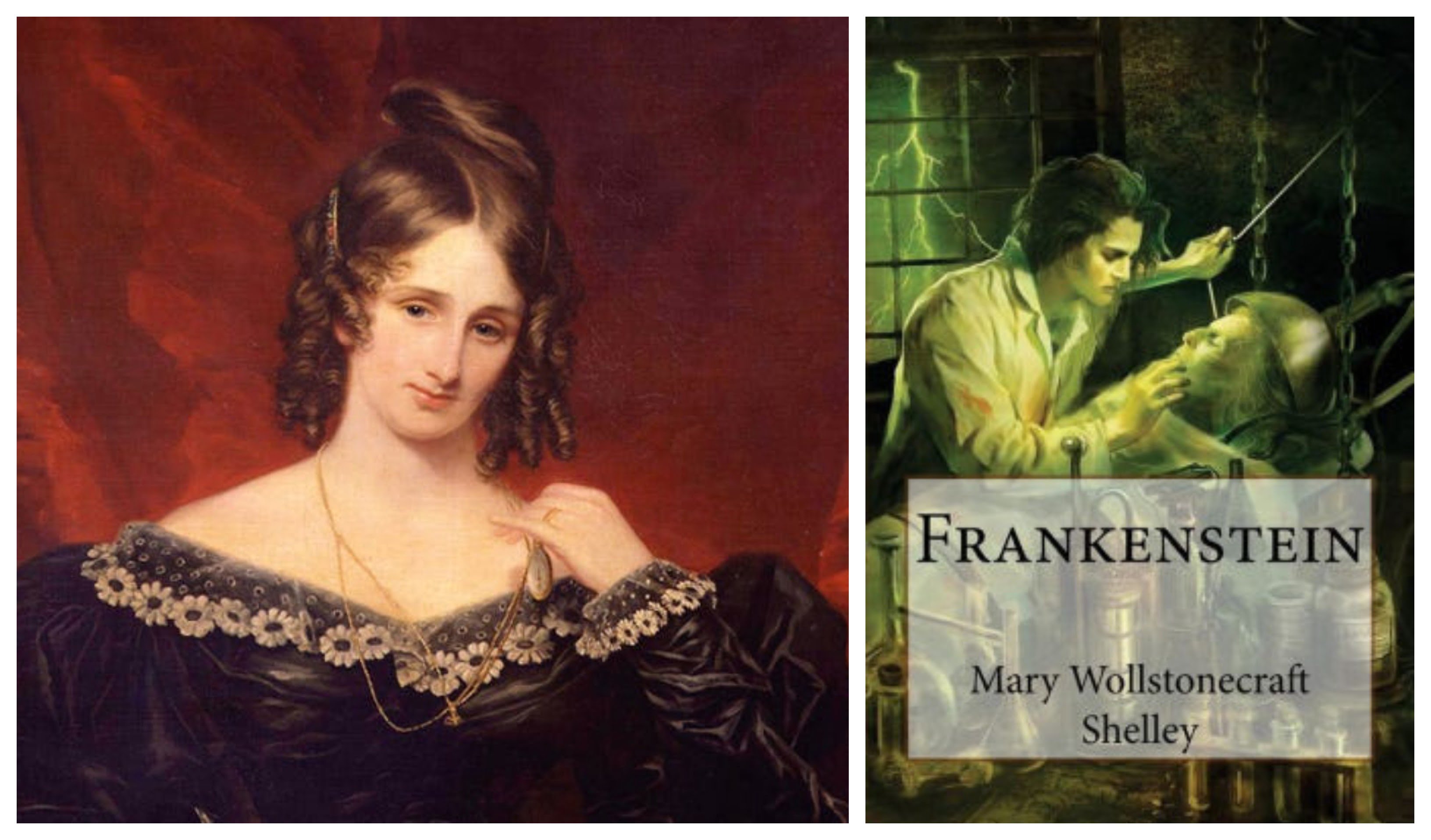

It is tough to live up to your parents’ expectations. Who could have known this better than Mary Shelley, the daughter of two of the most radical and prominent philosophers of the eighteenth century? Mary Shelley was the child of William Godwin, a major political philosopher of Britain and Mary Wollstonecraft, a.k.a, the mother of feminism, who in her trailblazing work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman laid forth the argument of women’s emancipation in a patriarchal society, which essentially required women to just “procreate and rot”. Today, Mary Shelley remains as widely read as her parents (perhaps even more, because who doesn’t prefer a good gothic story over a political treatise), largely owing to her debut fictional work Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus (1818) which not only became a seminal gothic work, but also kicked off the larger genre of science-fiction. Yes, you read that right! The genre of science-fiction was inaugurated by a young woman, who was only twenty-one when one of the most influential work of literature was published in 1818.

While continuing in her mother’s footsteps, Shelley did work for the outcast women in the society, but the trait of feminist awareness in her work was largely ignored. It wasn’t until the feminist criticism in the late twentieth-century that critics uncovered an implicit attack on science and patriarchy in her gothic novel Frankenstein, showing Shelley’s awareness of the subjugation of women in a world-driven by reason, science and patriarchy. This might come as a surprise because Frankenstein barely features any strong, independent female character and ironically most of the female characters die by the novel’s culmination. However, it was precisely in the negation of female characters, that Shelley sought to explore her most relevant question.

The death of female characters in the novel is alone to raise enough feminist eyebrows to question how science and development is essentially a masculine enterprise and subjugates women

Frankenstein revolves around its eponymous character, Victor Frankenstein, an ambitious scientist who tries to undo nature’s cycle by bringing back the dead to life. In his isolated laboratory, Victor manages to reanimate a corpse – but disgusted at his own monstrous creation, he abandons it. The creature, wanting to be loved and accepted by the world, is filled with wrath against his master and wreaks havoc on his life, asking for a female companion to compensate for his isolated existence. Victor initially agrees, but realizing that his creatures might procreate and lead to the annihilation of the human race, Victor tears his female creation to pieces. The monster swears revenge, leading to an ultimate tragedy.

The death of female characters in the novel is alone to raise enough feminist eyebrows to question how science and development is essentially a masculine enterprise and subjugates women (a theory later championed by ecofeminism). However, the most thought-provoking feminist reading of the novel has been done by scholar Anne Mellor in her book Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters where Mellor states that Frankenstein is a feminist critique of science itself. The creation of a new being is done by Victor solely without any female assistance, which is both unnatural and patriarchal. Mellor notes, “In trying to have a baby without a woman, Victor Frankenstein has failed to give his child the mothering and nurtarance it requires, the very nourishment that Darwin explicitly equated with female sex.”

Also read: Gender-based Violence: 5 Books & Literature As Witnesses

Victor, thus by, bestowing life upon a creature, not only usurps the power of god but also of women. Burton Hatlen in his essay “Milton, Mary Shelley and Patriarchy” extends Mellor’s argument by pointing out how under patriarchal mythos, the act of creation is seen as exclusively male and the female at best is just a ‘vessel’ that just contains the life generated by men. The creature, thus created, by Victor, is not given any love, care and affection generally associated with femininity. Hatlen mentions that this removal of the mother from a patriarchal family, reduces the child to the mere status of an object. Movies like Splice and Morgan which carry on the mythos of Frankenstein also point out the same.

There seems to Be A feminist fear in Shelley, as she saw female roles being completely negated in her society.

It is important to understand the context in which Shelley wrote Frankenstein. The late eighteenth century was a period of industrial revolution, which saw the speedy establishments of factories and machines. The machines, in turn, left many women (and men) unemployed, whose cottage-based industries collapsed under the pressures put on by the capitalist market posed by the industrial revolution. This was also a time when the domain of science was entirely a male-driven enterprise. There seems to be a feminist fear in Shelley, as she saw female roles being completely negated in her society. In an age of genetic engineering, which seeks to create hybrids of animals without the natural act of procreation, a cautionary tale like Frankenstein could not be more relevant.

The biographical movie Mary Shelley (2017), while not entirely a faithful rendition of Shelley’s life, features a really memorable scene towards the end when a young Mary (played by Elle Fanning) goes to a publisher to get her novel published. The publisher is incredulous of such a profound story of pain, guilt and loss being written by a woman, dismissing it to be the work of her husband Percy Shelley. Mary aptly replies, “Do you dare question a woman’s ability to experience loss, death, betrayal – all of which is present in this story – my story!”

Also read: The Madwoman In The Attic: How “Mad” Was Bertha Mason In Jane Eyre?

Frankenstein pioneered the genre of science-fiction and its influence pervades the popular culture, with many adaptations and retellings. Mary Shelley has already been hailed as a revolutionary figure in the genre, but people little know of her feminist stance, which formed the core message of her debut and most acclaimed novel. Shelley, as a young writer, was not intimidated by her familial legacy nor with her association with other male contemporaries like Lord Byron and her own husband Percy Shelley. In the Romantic canon, if there is one woman whose influence cannot be denied, it is in fact: Mary Shelley. Or Mary ‘Wollstonecraft’ Shelley, as she liked to call herself.

Reference

The Introduction and Essays from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, edited by Maya Joshi