As your swooping shadow deepens night’s ink

I flare in love, afflicted, sleepless. Your softest

Southern breeze fans my passion. Help me.

I could blaze to death

Andal, Song Eight: Dark Clouds be my Messenger.

The Indian philosopher and writer T.M.P Mahadevan said ‘as philosophy and religion is not divorced from each other in India, the great Indian philosophers have all been saints.‘ Bhakti as a movement emerged in Tamil Nadu between 6 C.E. and 7 C.E. The etymology of the word “Bhakti” is derived from Sanskrit where the word Bhaj means “to worship.” After the end of the Sangam period in Tamil literature, Bhakti movement marks a significant shift in literatures that have been produced. It focuses on the extreme passionate devotion towards the God without limiting oneself to a categorised social institution. Out of 12 Alvars (Vishnu worshippers), Andal is the only female poetess/ saint who is worshipped for her unabashed desires and devotion towards the lord Vishnu.

Andal as a child was abandoned in the garden of Periazhwar who used to string garlands for lord Vishnu in the temple. He was said to be childless until he found Andal and named her Kothai. It is believed in Tamil Nadu that Andal is an incarnation of the goddess Lakshmi. The irony of this narrative however is that, in a patriarchal society even the female goddess does not have space in the family until an upper caste family adopts her. Andal grew up in a brahmin household with deep devotion towards Vishnu.

Her rich contribution to Tamil literature is glossed over by the attribution of motherhood and through this process her works are desexualised.

Like Mira and Radha, she desired the god without shying away from the notions of abstinence that is expected from women. Her famous works are Thirupavai and Nachiyar Thirumozhi in which she portrays her intense desires and needs towards her lover. In the month of Margazhi in the Tamil calendar, Thirupavai is sung in most of the Tamil households, remembering and recollecting memories of Andal.

Andal is an important archetype to understand the repressiveness of patriarchy in the Tamil society. Her works could be categorised into two parts. One, which talks about her sensuous body and the struggle to contain her desires for her lover; and the other, that does not involve eroticism and is filled with eclectic preaching. Despite her vast array of works in the former domain, she is known and prayed for her latter works which is devoid of eroticism.

Andal’s works that only involves devotion and her desire to get married to Vishnu is popularized in the society and amongst families. The sanitized image that is painted of her reflects that particular nature of society which constantly pushes aside anything that does not fit within its moral code. This however, is only restricted to women because the deep sensuous desires of the other 11 male Alvars do not go through severe scrutiny and censorship in the eyes of the society.

“I dissolve in anguish awaiting his glance.

But the duplicitous Lord of Govardhana

Cares not if I live or die though he rains attention

On everyone else. If that looter, that

Plunderer but look in my direction I shall pluck

out my useless breasts by the roots and fling

them at his chest”

~Nachiyar Thirumozhi

It is said that Andal put on the garland that was made for Vishnu and seeing this act as sacrilegious, her father was infuriated and refused to adorn Vishnu with the same garland that Andal wore around her neck. However, later that day Vishnu appeared in Periazhwar’s dream and said he is pleased with the gesture of Andal. Periazhwar, taking this as a divine command began to nourish Andal’s love for Vishnu.

The story of Andal’s marriage to Vishnu is distorted and has several versions amongst the Tamil society. It is believed that she was taken to Srirangam in her bridal robe and as she reached close to the statue of Vishnu, she was absorbed into it. This narrative is considered as the fulfilment of marriage of Andal. Since, she is understood to be married to Vishnu, Andal is referred to as ‘Amma’ which translates to ‘Mother’ for all Vaishnavaits.

Also read: Panels, Politics, and Penn (Women) In The Land Of Tamil Nadu

The problem with the construction of Andal as a ‘mother figure’ is relevant even today. Her rich contribution to Tamil literature is glossed over by the attribution of motherhood and through this process her works are desexualised. The notion of a woman writer exhibiting her desires becomes unbearable in a society that constantly finds a way to erase the autonomy over her body. Attributing motherhood is a way through which protective masculinity is invoked among men and the more woman gets desexualised, the more she is protected by men around her. Patriarchy rejects the idea of mothers possessing any kind of sexuality of their own reducing them to the only position of care givers to the family.

This notion could be reflected in the incident that took place in Tamil Nadu when Vairamuthu, a famous lyricist spoke about Andal and her contribution to Tamil literature. In one of his statements he said that Andal is ‘a devadasi who lived and died in the Srirangam temple.‘ This statement created massive disruption among the Hindu community and Vairamuthu was criticized and threatened. Devadasi literally means the servant of god and post colonisation, the tradition of Devadasi has gained an image of being ‘immoral’ and it is associated often with the profession of ‘sex work.’

In a highly patriarchal society, it has always been a struggle for women to freely exhibit their potentialities without facing hindrances from the society.

However, it is interesting to look into the arguments placed by Hindu followers where they constantly called out Vairamuthu for having defamed their ‘mother.’ The idea of ‘motherhood’ is so strong that it provokes patriarchal men to stand in solidarity to defend their pride and ideals which they see in their mother. This construction becomes toxic, when one attempts to understand or study women’s work. Religion here intricately entwines into the language of our everydayness and it clouds our secular outlook towards art hence only catering to what patriarchy demands.

Also read: How Nesamani Became The Voice Of Dissent Of Tamil Nadu

This ‘sanitization’ has segmented works of Andal and blinded us from the knowledge of the entirety of her work. In a highly patriarchal society, it has always been a struggle for women to freely exhibit their potentialities without facing hindrances from the society. They are either demonised and if they have religious affiliations, they are mystified and desexualised. Hence it becomes pertinent for us as a community to stand by one another and make “a room of one’s own.”

References

- Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess by Priya Sarukkai Chabria and Ravi Shankar.

- Women Saints in Tamil Nadu by K.C. Kamaliah.

- Embodying Motherhood: Perspectives from Contemporary India by Anu Aneja, Shubhangi Vaidya.

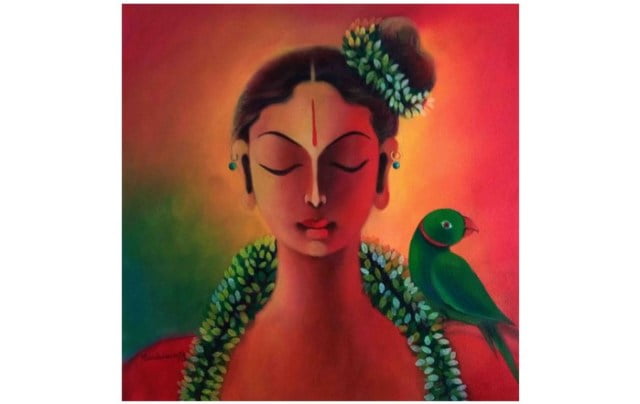

Featured Image Source: WordPress

About the author(s)

Divya Krishnamoorthy loves listening to stories and believes that we are all stories who stay alive only through narration. She is a Masters student in English at Ambedkar University, Delhi. When she is not writing her papers, you will definitely find her having one of her weird reveries.