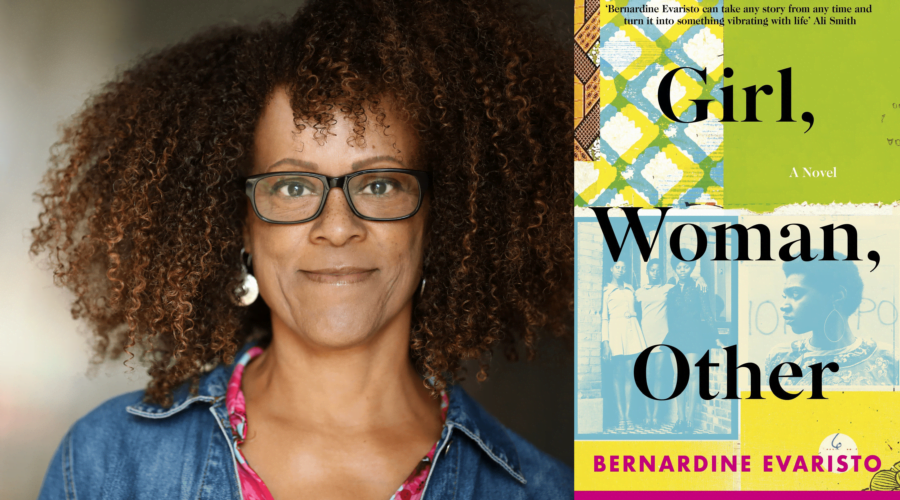

Womxn of unheard voices and unsung praises are at the heart of Bernardine Evaristo’s 2019 Booker Prize-winning novel ‘Girl, Woman, Other’. It is a book that puts presence back into absence. Within these pages are, not one but twelve black British womxn, all scripting their own individual stories within Evaristo’s master narrative. It is a joyful counterpoint to the near invisibility of womxn of colour in literary productions—both as authors and as their fictional creations.

“We the women

Whose praises go unsung

Whose voices go unheard…”

—Grace Nichols, I Is a Long Memoried Woman (1983)

Evaristo’s protagonists are a diverse bunch, full of contradictions. Questions of Identity, otherness and togetherness define their stories. But identity and otherness are not fixed but layered and contested categories. And in this fluidity, lies the possibility of togetherness. The womxn who inhabit its pages seem to say, ‘Here we are, as inspiring and flawed and heterogenous as everyone else, and our bonds are stronger and our stories more fascinating because of it’.

The Hyphenated Identities

In the twelve chapters of Girl, Woman, Other’, each of which revolves around one protagonist, female identity is a truly intersectional experience. Coming from a feminist and a trans-aware perspective, Evaristo complicates the experience of womxnhood as she throws class, ethnicity, age, sexuality, trans identities and disability into the mix. As if to underscore this slipperiness, she introduces her characters in hyphens. Amma is a socialist-polyamorous lesbian-playwright; Megan/Morgan is a trans-non-binary-high school dropout-socia media influencer; Dominique is a lesbian feminist-domestic abuse survivor-transexclusionary-music festival producer. Their hyphenated identities present them to us as complex, flawed and messy beings, each with their own distinct voice. Some are homophobic, some are feminists, some decry feminism, some don’t know what feminism is.

Their hyphenated identities present them to us as complex, flawed and messy beings, each with their own distinct voice. Some are homophobic, some are feminists, some decry feminism, some don’t know what feminism is.

Hyphenated identities also complicate our understanding of who is the ‘other’. While as black womxn, they all occupy that category to some extent, the ascription of otherness is also constantly shifting. As a non-binary trans person, Megan/Morgan spends their early life feeling othered till they discover their own individual identity and community. For them, acceptance comes from the least expected places. Born to Nigerian immigrant parents from a working class background, Carole spends her entire life trying to fit in. She feels “crushed, worthless and a nobody” at Oxford, and later, in the white male planet of investment banking.

At the same time, she feels misunderstood by her immigrant mother, Bummi, who fears that Carole’s success is a rejection of her “true culture”. Bummi gives Carole an English name, knowing that a Nigerian name will hold her back. But when Carole does get on, a gulf opens up between them. Otherness is also projected from one body to another. As an adopted child and the only womxn in an all-male teachers’ room, Penelope displaces her own sense of otherness on to the new young black teacher Shirley.

The Other

Often, the feeling of being the ‘other’ leads to big and small betrayals and fallouts between friends and lovers, mothers and daughters, and mentors and students. But they also bring with them the possibility of togetherness. There is something unconditional about these relationships. The womxn get past tensions and conflicts to forgive and support each other. When differences seem insurmountable and reconciliation impossible, the storyline gently nudges the protagonists—and by extension the reader—towards a position of empathy. In a symbolic final act, the protagonists converge and interact at Amma’s after-party on the opening night of her play. Not all of them know each other. They variously love, hate, or are indifferent to each other. They are there to support and cheer Amma, or to simply watch the play, write a review, and socialise. At any rate, in those moments, these motley characters find a reason to come together.

Togetherness comes despite contentious conversations. What we do make of the homphobic woman who remains deeply loyal to her lesbian friend? What do we make of the politics behind the assertion that “only a black woman can ever truly love a black woman”? Especially when it becomes a ruse for emotional manipulation and abuse in a lesbian relationship? What should our ethical stance be when we discover that the survivor of that same abusive relationship is also trans-exclusionary? Do we show anger towards those who “get it wrong”, even if it comes from a place of ignorance instead of hate? Who is the “most privileged” and is there a sliding scale anyway?

Togetherness comes despite contentious conversations. What we do make of the homphobic woman who remains deeply loyal to her lesbian friend? What do we make of the politics behind the assertion that “only a black woman can ever truly love a black woman”? Especially when it becomes a ruse for emotional manipulation and abuse in a lesbian relationship?

It is to Evaristo’s credit that she does not shy away from these uncomfortable questions, even though the scope for meaningful engagement is limited. These are questions where political discourse often fails us and there is no reassurance of ready answers. These are questions that we, as feminists, activists and womxn who come from a broad spectrum of intersectional heterogenous identities, grapple with everyday, in our own contexts and situations.

This is why Girl, Woman, Other’ that is predominantly about black British womxn, also speaks to me, as a South Asian womxn and feminist. It amplifies the voices of womxn of colour without turning them into a monolithic category. It speaks to womxn from diverse contexts without collapsing their differences. This is Evaristo’s great achievement. For her and her fictional mavericks, togetherness does not erase difference, neither is it contingent on sameness. Instead, it comes from a place of empathy that reaches out out despite differences.

The Girl, The Woman And The Other

This is what makes ‘Girl, Woman, Other’ a significant literary contribution in our contemporary times when the mere allusion to difference and privilege elicits accusations of identity politics. While it speaks specifically of a black British feminist politics, it is as relevant for South Asian feminist activists struggling for a more inclusonary feminist politics that is conscious of difference, looks for shared interests without erasing difference, and refuses feminism(s) which won’t address exclusions based on difference. As one of Evaristo’s characters put it, we need to be especially alive and responsive to difference at a time when “…many more women are reconfiguring feminism…grassroots activism is spreading like wildfire and millions of women are waking up to the possibility of taking ownership of our world as fully-entitled human beings”.

Also read: Book Review: With Ash On Their Faces By Cathy Otten

Ironically, the marginalisation of the voices of womxn of colour and the lack of attention to difference was most obvious in the reception to Evaristo’s book, especially in light of the Booker Prize controversy. The Booker Committee’s decision to reverse its own long-standing rule to only pick one winner, came the very same year when a black woman won win a Booker for the first time. A historic win for Evaristo thus became a shared honour with Margaret Atwood’s Testaments. This was Atwood’s second booker, and Evaristo’s first. As several commentators have pointed out, as the first black woman to win the Booker, Bernadine Evaristo deserved to win alone. It was an opportunity for the committee to reverse a pattern in which books by womxn writers of colour have had to jostle for space, leave alone recognised. By refusing to do so, the committee’s decision reinforced the same ‘otherness’ that Evaristo seeks to rewrite.

And it wasn’t just the Booker Committee. The Guardian described her as an obscure writer despite the fact that she has spent two decades in publishing and is the author of seven acclaimed books before this. More recently, a BBC news presenter referred to Evaristo as “another author” while discussing her joint Booker victory. These are far from isolated reminders that certain voices are always at risk of being ‘quickly and casually removed from history’.

Evaristo’s trailblazing work challenges and subverts this dominant tendency. But it is contingent on us, as readers, to amplify the voices of authors like her. Whether it is by supporting bookstores that house works by womxn and queer authors of colour, retreiving lost voices from the archives, archiving similar works in our contemporary times, or reading and writing about them as part an intersectional feminist politics.

Also read: Book Review: Forsaken: An AIDS Memoir By Alexandre Bergamini

While inextricable from my politics, Girl, Woman, Other’ also speaks to me on a more personal note. For me, part of the power of literary fiction lies in the relationship it builds between the reader and the message, and this relationship leads to empathy and a wish for change. No other book I have read recently proves this point as well as Evaristo’s wonderfully creative account of womxn in the world.

Note: I have used the word ‘womxn’, instead of women/woman, as an all-inclusive term since a few characters in this book identify as trans/non-binary. I have, however, left women/woman unchanged in the book title and quoted excerpts.

Featured Image Source: Wasafiri

About the author(s)

Sohel is a feminist researcher-writer, a journalist, and currently a postgraduate student of gender studies at SOAS, University of London.