In the 2002 movie Devdas directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali, there is a particular scene in which Paro’s mother visits Devdas’ mother to initiate talks of their marriage. Devdas’ mother has an inclination of this proposal but doesn’t seem to think Paro is a ‘proper’ match for her son. She asks Paro’s mother to perform for a gathering for, after all, her family used to be Jatra performers. Paro’s mother who has already been established as a ‘loud’ woman (through the kind of clothes that she wears, her tone while she talks and the language that she uses) performs for the gathering but when she approaches Devdas’ mother with the proposal, she is ridiculed. “Tumhari adaa mein riyaaz nahi lekin khoon toh vahi hai, nautanki wala,” (Your charm might be out of practice but your blood is still the same, that of a lowly performer) says Devdas’ mother before dismissing the proposal with “Apne khote sikke ko yahan chalane ki koshish mat karna,” (don’t try to work your tainted money here).

This is a significant scene that explores the class, caste and gender angles of being a Jatra artist.

In her essay Marginalization of Women’s Popular Culture in Nineteenth Century Bengal, Sumanta Banerjee delineates how the rise of the Bengali bhadralok along with the ‘white man’s burden’ of the British men led to a careful eradication of women’s role in popular culture. These women were specifically from lower socio-economic groups and hence, there was much disparity between their social lives and those of the British rulers or the recently English-educated bhadralok or bhadramahila.

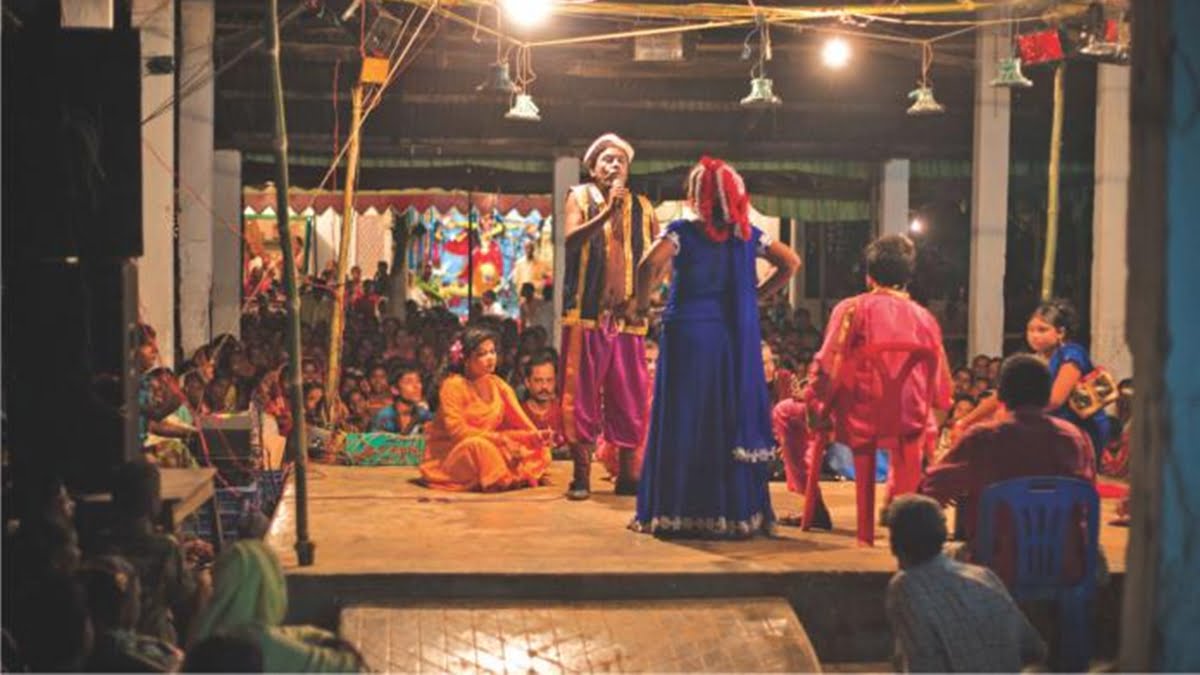

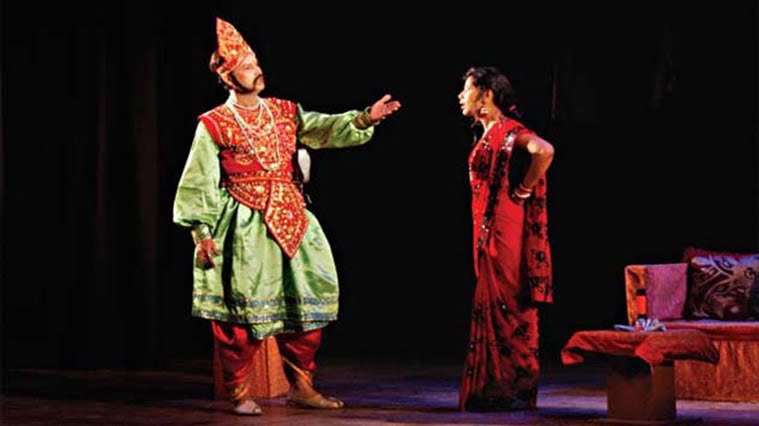

Jatra’s origins are a bit ill-defined. However, popular narrative traces its origins to folk-drama which then developed into Jatra, as we know it now, under the patronage of the Chaitanya movement in 16th century Bengal. This, however, does not mean that other religious sects did not use Jatra to spread their message and faith.

Also read: Why the Growing Number Of Women Taking Up Kathakali Is Heartening

Jatra’s origins are a bit ill-defined. However, popular narrative traces its origins to folk-drama which then developed into Jatra, as we know it now, under the patronage of the Chaitanya movement in 16th century Bengal. This, however, does not mean that other religious sects did not use Jatra to spread their message and faith. In his study, Jatra: The Popular Traditional Theatre of Bengal, Pabitra Sarkar says that although Krishna-jatra or Kaliya-daman jatra were the most popular Jatra palas (plays) for a long time, there was also considerable interest in Chandi-jatra, Manasar-bhasan jatra and Ram-jatra. Later, there was a certain secularisation of Jatra, a shining example of which was the famous story of Vidyasundar by Bharatchandra Roy adapted into a Jatra pala. However, soon Jatra along with many other popular art forms started to be seen as vulgar and gross.

Jatra was seen as a degenerate art form on two accounts – one, it used licentious language. This language could not be accommodated by either the Victorian British logic or the ancient revivalism project of the bhadralok. Second, it was attacked for allowing women to participate in roles which were deemed improper for womenfolk. Here, however, the British and the bhadralok had differing arguments to make. The British saw these women as simply unenlightened and hence in need of saviours – that is, the British men. The bhadralok, however, saw these women as impure and promiscuous. For them the correct way to be a woman was to be an educated bhadramahila who spoke her mind but within the confines of the andarmahal or zenana. The working women who came from the rural areas and widely participated in Jatra were seen as threats especially when they interacted with the upper class women. Banerjee notes that working women often composed songs about their occupations and their dances provided for comic relief in Jatra.

A lot of articles were written rebuking these popular art forms and those who practiced or performed them. Banerjee in her study notes how a bhadralok described Jatra – “The gesticulations with which many of the characters in these yatras recite their several parts, are vulgar and laughable.” Another bhadralok asked, “…and who that has any moral tendency will not censure the immorality of the pieces that are performed?”

A statement that explores the class and caste narrative of the attack on Jatra is by Sanjeev Chandra, brother of Bankim Chandra Chaterjee. He says, “Anyone from among the illiterate fishermen, boatmen, potters, blacksmiths, who can rhyme, thinks that he has composed a song… But there is nothing in this song except rhyming… Thanks to the present type of jatras, Krishna and Radha look like goalas (milkmen); in the past, the qualities of a good poet made them appear as divinities.” Through this statement we can perhaps deduce that there was a definitive attempt at chalking certain occupations and people who occupied them, as lowly, incapable of writing good poetry. The attribution of human passions to the deities is seen as another act of contempt, one that was directly fed by the British Victorian narrative of morality. But while the male Jatra performers could be accepted in the social milieu granted they made some changes to their form and structure, the female Jatra performers were the one to bear the brunt.

While the male jatra performers could be accepted in the social milieu granted they made some changes to their form and structure, the female jatra performers were the one to bear the brunt.

At one point women played all the different roles in the Jatra palas and added music through cymbals, clapping and kettle drums. This, however, soon changed. Women performers were branded as sex workers and this identity was then looked down upon. With the growth of the theatre plays in the European style, women performers were extensively cut off. Although post 1870s, with the campaign by Madhusudan Dutt, women were accepted in roles in theatre plays and some of them such as Binodini, Golapi, Elokeshi and Shyama became famous on the stage, there was generally very limited acceptance of female artists. This is probably best expressed through a statement by Manomohan Basu where he said it is better to watch male Jatra performers than to allow women to act and destroy religious principles on stage. The few female theatre artists that did carve a space for themselves had to work much harder to be an asset to the art form and they stayed in a constant act of negotiation.

Recent times have seen a revival of Jatra. The plays have incorporated social issues that impact women and we know of Chapal Bhaduri whose female impersonations defy gender norms in a significant way. However, the chasm created between the rural women who belonged to lower socioeconomic class and the current form of Jatra being embraced by the urban community still persists.

Also read: What Kathak Means To Me And My Struggle Against Misogyny

What happened to the female Jatra performers, then, is in some ways similar to what happened to the devadasis and their performance of Sadir. Sadir was sanskritised into Bharatanatyam which was accepted into the upper-class narrative at the same time that devadasis were cut off from it.

What happened to the female Jatra performers, then, is in some ways similar to what happened to the devadasis and their performance of Sadir. Sadir was sanskritised into Bharatanatyam which was accepted into the upper-class narrative at the same time that devadasis were cut off from it. We probably don’t have to look too deep into the history of regional art to realise that many women artists who subverted the dominant narrative saw a similar fate. In the vein of what T.M. Krishna beautifully expounds on in Reshaping Art, I would like to say that female Jatra performers did not accommodate middle-class or upper-class moralities. Their very existence was a threat that demanded recognition of subaltern art forms. So they were shamed, ridiculed and marginalised until their experiences were effectively erased from the majority narrative.

Featured Image Source: The Daily Star

About the author(s)

Isheeta is a features writer, a student of History and a prospective student of Gender Studies. She enjoys reading historical fiction, philosophy, gender theory and sipping coffee in quiet corners.