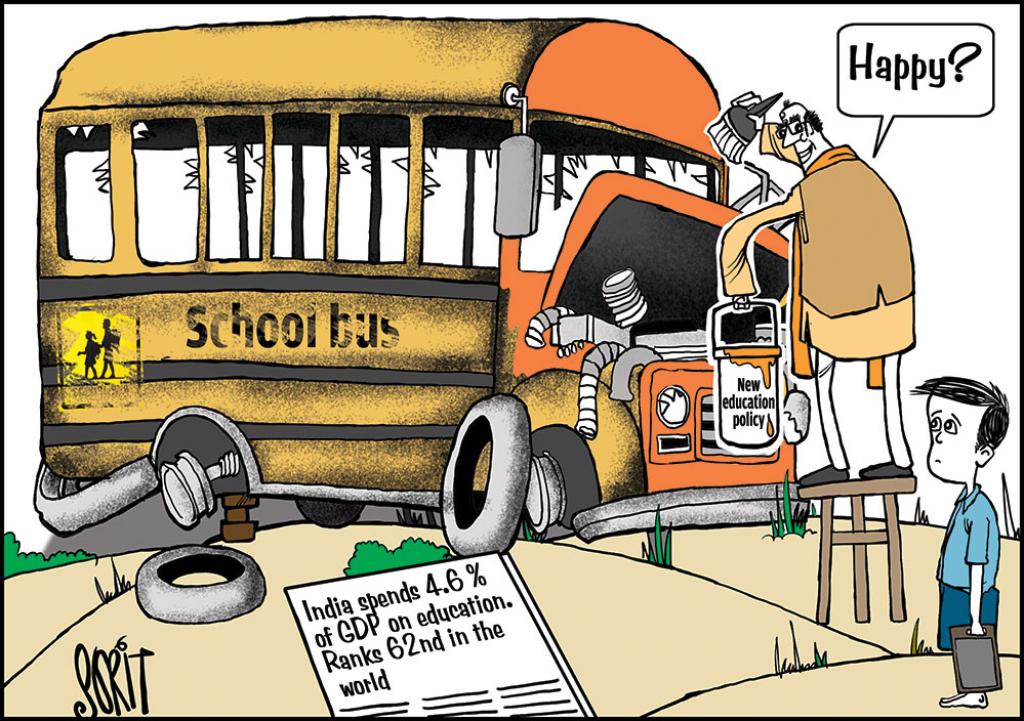

Almost two months ago, the Union Cabinet had approved the New Education Policy (2020), making several drastic changes to the previous policy that had been formulated more than three decades ago. As per the current government, the policy strives to work for achieving access to quality education for every child while also revising the framework of school and higher education in India.

Its key proposals include, inter alia, replacing the schooling model of 10+2 to 5+3+3+4 by paying adequate focus on the foundational years of children in both government and private schools; making possible the attempting of Board Examinations twice; offering multiple entry and exit options for an Undergraduate Degree of 3 or 4 years with a provision of storing ‘transferable credits’ earned from an incomplete degree that can be redeemed at a later point in time; providing options for year-long Masters Programmes; discontinuing M.Phil. as a course and most importantly making education multidisciplinary by removing any hard separations between the Sciences and Arts, Curricular and Extra-Curricular, Vocational and Academics.

Notwithstanding such bold and much-needed changes in the education system that might seem progressive on paper, but enormously tough to achieve in a country like India that survives on a highly fractured education system in the status quo; the New Education Policy does not make it hard for one to observe and visualise some of its key fault lines that are currently being addressed and debated by a limited number of critics and educationists. (Please note that the following list is non-exhaustive.)

the new policy aims to set up a single Board of Governors (BOG) that would be entitled to make decisions with regard to significant issues like students’ fees, academic curriculum and schedule, the number of students to be enrolled and the number of teachers to be appointed, salary structures, promotions etc.

1) Centralisation of the Education System

Initially, the Indian Constitution had mandated for Education to be kept as a ‘State Subject’ which was then later shifted to the Concurrent List in 1976. Thus, the country followed an increasingly federal approach while executing education and learning strategies. However, the new policy aims to set up a single Board of Governors (BOG) that would be entitled to make decisions with regard to significant issues like students’ fees, academic curriculum and schedule, the number of students to be enrolled and the number of teachers to be appointed, salary structures, promotions etc.

The board would act as a single regulator by replacing the existing bodies like the UGC, AICTE, NCTE. There are high possibilities that such a single board of governors could clampdown the grievances of certain educational institutions and also mandate the spreading of the ideological agenda of the ruling party by furthering its capital interests.

2) The Dilemma of the Medium of Instruction

The NEP 2020 continues the use of the three language formula in schools; however, it stresses on two languages out of these three to be vernacular. What is also to be carefully examined is the fact that the policy places a special emphasis on Sanskrit in today’s current context of Saffronisation. It also advises the states to choose the native mother tongue as the medium of instruction till class five. This perhaps has become the most heated point of contention since the policy does not elaborate about the tenets and viability of such a position.

With most regions having a diverse range of local languages, such an imposition of one regional language for all creates significant confusion with respect to its implementation. The policy also does not specify as to how such an enforcement would turn out for students with cross-cultural parents or for those who might have migrated to other cities. Moreover, the cosmopolitan nature of Indian cities does not cater to only a single regional language, thus contradicting such a proposal.

One sole result that appears to reflect from such dimensions of the policy is that it is highly likely that English will be stripped from its stature of being the commonly used medium of instruction. And the implications of this seem to be most detrimental to the learning experiences of the marginalised who do not have the resources to invest in learning English through external sources (private tuitions), if not from schools. Thus, in the longer term, such language barriers would essentially restrict their connection to the largely globalised world and would end up prohibiting their social and occupational mobility.

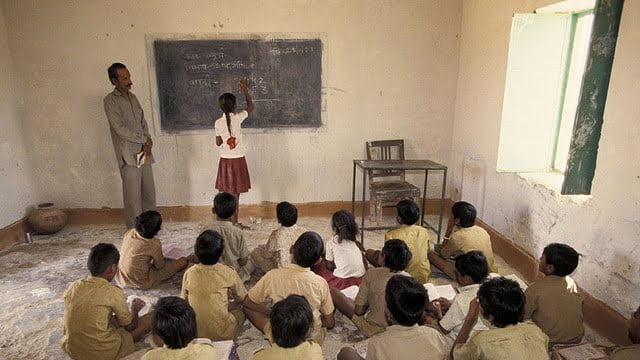

3) Lack of Infrastructure and More of Rhetoric

The policy promises the universalisation of foundational classes as a part of the new 5+3+3+4 model without addressing problems like the lack of infrastructures for the same. Even though there is a mention about providing the ‘Early Childhood Care and Education’ training to teachers/Anganwadi workers (without any mention for their adequate compensation) and ensuring the same for all children, it does not lay out any financial or policy roadmap to achieve this.

The Policy also mentions about extending the ambit of the Right to Education Act by making education free and compulsory for children from 3-18 years of age; however, there seems to be no clarity with respect to how this would pan out in private schools that often complain about not being reimbursed timely for their RTE dues.

Moreover, such an extension can only fully come into effect if a legal amendment is proposed to edit the RTE Act of 2009 that provides free and compulsory education to children from 6-14 years of age, as is currently practised. The policy chooses to remain silent on this. Thirdly, the policy demarcates 6% of the GDP to be employed for facilitating education, however, with a meagre 3% being spent in the year 2018-19, such an ambitious jump seems far-fetched.

4) Question of Gender Inclusion

With regard to this, the policy proposes the formation of a Gender Inclusion Fund in order to promote equitable access to women and transgender students who are underprivileged. It also mentions the institution of Special Education Zones (SEZs) for this purpose that shall be run by philanthropist partnerships; thus absolving the government from its duties.

The fact that the policy overemphasises on digital learning online courses in regional languages while giving no details about a suitable infrastructure that can enable such an objective is yet another flaw on its part. It is important to note that the provisions of learning from home through digital means would also restrict the freedom of girls from physically attending school campuses.

The policy also does not mention any longterm institutional redressal mechanisms to reduce cases of sexual harassment or child abuse while also not making scope for providing a definite framework as to how gender and caste sensitisation on educational campuses can be promoted while simultaneously also looking into dimensions of tackling identity-based violence.

Moreover, when compared to men, a smaller percentage of women have access to the internet and technological devices, therefore such a provision would drive towards their exclusion from gaining access to knowledge. The policy also talks about consolidating nearby school complexes; this too shall restrict them since even today girls are not permitted to travel far to pursue education. Another significant factor that leads to girls dropping at an early age is the lack of menstrual hygiene management at schools. Unsurprisingly, neither is there a mention about facilitating access to menstrual products such as sanitary products in the policy or increasing female-friendly toilets.

Image Source: Safety Kart

The policy also does not mention any longterm institutional redressal mechanisms to reduce cases of sexual harassment or child abuse while also not making scope for providing a definite framework as to how gender and caste sensitisation on educational campuses can be promoted while simultaneously also looking into dimensions of tackling identity-based violence.

Also read: Sexual And Reproductive Health: The Missing Link In NEP 2020

5) Ambivalence and Minimal Provisions for Mitigating Inequalities

The policy very conveniently clubs up all students from the deprived backgrounds by using ambivalent terms like Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Groups (SEDGs) and does not explicitly mention about provisions of reservations or equitable access to institutions for students from the SC and ST communities. It encourages private universities to give scholarships or ‘incentives’ in place for meritorious students from marginalised communities without declaring responsibility on the part of the government for the same.

With increased commercialisation of education and lack of sufficient funding, institutions—once autonomous—would resort to the option of increasing the fee structure for students. By such privatisation of education and allowing foreign universities to open campuses in India that would charge a high fee, the policy would widen the gap between the financially capable and incapable students who would then be forced to dropping out from these inaccessible institutions.

6) Lack of Deliberation

Immediately after the draft of the policy was released in 2019 and approved in July 2020, it was received with great scrutiny and reasonable critiques from various sources while there was also a great uproar, asking for its rejection. As mentioned earlier, the current subject of Education falls under the Concurrent List, therefore the policy subject of the draft demanded making space for hearing out the objections and inculcating the suggestions from State Governments, eminent educationists and other stakeholders. However, the hasty manner in which the policy was approved with the Parliament being bypassed in the process is to be questioned.

Whether the release of the New Education Policy was a political stunt or a well-intended initiative towards reforming the core principles of the outdated Indian Education system will only be revealed in the future coming years with its full-fledged practice on the ground.

It also becomes important to foresee and question the intentions of the Union Government regarding the proposal of multidisciplinary learning in a time when sections like secularism, democratic rights, citizenship are being ‘selectively’ excluded from the current curriculum under the garb of reducing duress during a pandemic. Therefore, one has to be wary of the ways in which future course material would be designed.

The current pandemic also corroborates as to how the digital divide in India has selectively excluded those who belong to the marginalised caste and lower class communities and most of all, how the crisis has affected the access to education for young girls and women. Thus, there is a need for those in power to introspect on ways as to how every child can be integrated into the current education system rather than further widening the gap between the rich and poor.

Also read: The Glorification Of Mother-Tongue: Critiquing The Three-Language Formula Of NEP 2020

References

- A Deeper Look at India’s New Education Policy 2020

- NEW EDUCATION POLICY 2020 – The Good & the Controversial

- A Dictionary of National Education Policy 2020

Featured Image Source: Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Nidhi is an undergraduate student, pursuing English Literature and Political Science from St. Stephen's College. She is someone who's trying to understand the ways in which intersectionality and feminist politics have been shaping her evolving thoughts and ideas. Her new found interests include reading Urdu Poetry, listening to folk music and blogging.