While scrutinising over the questionable status quo that exists in the realm of Indian News Media, it would become highly noticeable to any insightful eye sensitive to diversity, that the representation of the marginalised in positions of leadership continues to remain dismal or in many cases almost nil. In this regard, ‘why not much rage is shown’ is not inadvertent, rather this signifies a serious and shocking decades-long over-presence of the privileged identities in all forms of media outlets who refuse to make space for the marginalised and remain complicit to exclusionary structures. Recognition of such a grievous problem, as well as provisions of inclusion are often misplaced with, or countered by rhetorics like ‘reverse casteism’. However, what is of more significance is whether such ideas and provisions are brought under practice in the first place even.

In observance of the exclusionary media houses and denigration of Dalits, Ambedkar had mentioned that the “Untouchables have no press” and had, therefore, professed the education of the marginalised such that they could pave way for carving out their opportunities. Not much has changed in the twenty-first century from the time back when he had spoken against this social disparity and underrepresentation of the marginalised communities within mainstream media circles that refused to publicise their stories.

Not much has changed in the twenty-first century from the time back when Ambedkar had spoken against the social disparity and underrepresentation of the marginalised communities within mainstream media circles that refused to publicise their stories.

Underrepresentation of the Marginalised Voices in Indian Media

With the release of the report (dated August 2019) titled ‘Who Tells Our Stories Matters: Representation of marginalised caste groups in Indian Newsrooms’ by Newslaundry and Oxfam, some media firms did start acknowledging the systemic fault in their diversity policies. However, it is only a matter of time after reports like these—that focus on issues such as the dominance of the savarnas in the Indian media—are sidelined again.

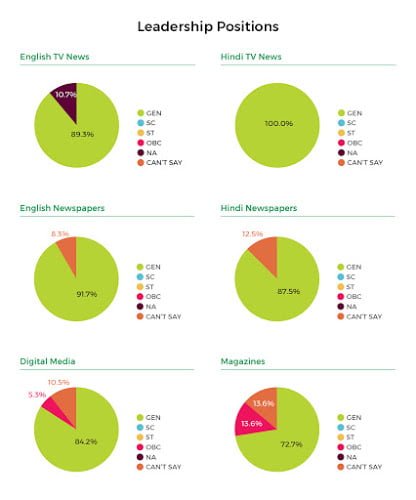

This aforementioned research was carried out between October 2018 and March 2019, making a shocking revelation later on that, “…out of the 121 newsroom leadership positions (editor-in-chief, managing editor, executive editor, bureau chief, input/output editor) studied across newspapers, TV news channels, news websites, and magazines, 106 were occupied by journalists from the upper castes, and none by those belonging to the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes.”

The report made a shocking revelation that out of the 121 newsroom leadership positions studied across newspapers, TV news channels, news websites, and magazines, 106 were occupied by journalists from the upper castes and none by those belonging to the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes.

Covering about seven English TV news channels (CNN-News18, India Today, Mirror Now, NDTV 24×7, Rajya Sabha TV, Republic TV, and Times Now) along with seven Hindi channels (Aaj Tak, News 18 India, India TV, NDTV India, Rajya Sabha TV, Republic Bharat and Zee News), the report highlighted that about eighty nine percent of the leadership positions among all these channels were occupied by those belonging to the general category. In the realm of digital media, eleven outlets (Firstpost, Newslaundry, Scroll.in, Swarajya, The Ken, The News Minute, The Print, The Quint, The Wire, Newslaundry- Hindi and Satyagrah- Hindi) were surveyed, out of which about eighty-four percent of the leadership positions were occupied again by those belonging to the general category with no representation from the Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes.

Similarly, in the case of thirteen newspapers (For English, the researchers selected The Economic Times, Hindustan Times, The Hindu, The Indian Express, The Telegraph and The Times of India. For Hindi, they chose Dainik Bhaskar, Amar Ujala, Navbharat Times, Rajasthan Patrika, Prabhat Khabar, Punjab Kesari, and Hindustan) that were studied, none had professionals from marginalised communities in leadership positions.

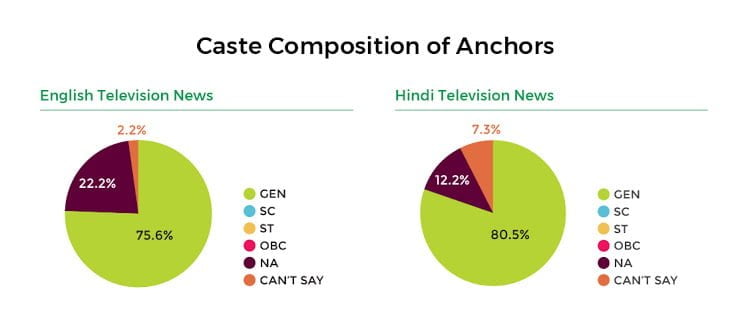

From October 2018 to March 2019, the seven English channels together telecast 1,965 shows of their flagship debates in which 1,883 panelists took part. Of the forty-seven anchors of these shows, thirty-three were upper caste. Similarly, eight out of every ten anchors of flagship shows across the seven Hindi channels were upper caste, and not one belonged to the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, or OBCs.

Simultaneously, a report released by UN Women (dated August 2019), titled ‘Gender Inequality in Indian Media’ revealed the egregiously low amount of gender diversity practiced by mainstream media houses. While 26.3 percent top jobs were held by women at online portals, TV channels employed a meagre 20.9 percent and magazines 13.6 percent women in leadership positions (defined as someone designated editor-in-chief, managing editor, executive editor, bureau chief, or input/output editor).

On the assessment of about thirteen newspapers with significant readership, none of them had a female head. Also, it was observed that most women reporters were assigned soft themes like Fashion and Lifestyle as opposed to hard themes like Sports, Politics and Business which were saved for men. The presence of Queer and Transgender journalists in decision-making positions continues to be nil. Despite several social barriers, Padmini Prakash became the first-ever transgender TV News Anchor in 2014 with Heidi Saadiya becoming the first transgender journalist in Kerala in 2019.

Similarly, while the representation of Kashmiri journalists in recognized posts of leadership remains almost nil, Muslims too continue to be severely underrepresented. This does not come as a surprise at a time when the mainstream news channels with immense viewership appear to be Islamophobic and continue to wage a hateful war against the religious minority.

Barriers that Discourage and Restrict Marginalised Sections

Socio-economic factors restrict occupational mobility and participation in professions like journalism for most marginalised groups even today. Their presence in the mainstream media hence continues to be bleak. Owing to the lack of economic support and exposure to or knowledge about opportunities, those belonging to marginalised caste identities end up being school and college dropouts and are forced into their ancestral occupations as a result.

The ones who do end up making it to reputed institutions of journalism and mass communication—that are most often spaces for upper caste and upper class English speaking groups of students—continue to face hostile reactions towards themselves. Because of the minuscule presence of marginalised identities in such classrooms, most of the time concealing one’s identity (Read: ‘Coming Out As a Dalit’ by Yashica Dutt) becomes the only resort to fend against the sentiments of hatred and disgust that are raged against them by the upper caste students. Even if they do ‘come out’, they are most likely to be judged for not being Dalit or Adivasi or Muslim ‘enough’ such that they fail to fit in the brackets of the definition of being marginalized as defined by the savarna eye and its notions.

Another severely damaging and skewed concept that is ‘merit’ relegates students belonging to marginalised groups—who access affirmative action while seeking admissions—towards bitter resentment on the part of the savarnas. This does not mark the end of the pursuit of a profession that involves endless struggles. Recruitment to a mainstream firm comes with the discriminatory screening at various levels and after being employed, marginalised groups such as women have continued to face problems like harassment at workplaces, the threat of violence and intimidation and have been denied promotions at a given scheduled time. Thus, experiences of exclusion and such glass ceilings discourage aspirants at each level of their journey to becoming a journalist or media person. Sudipto Mondal rightly puts it, “The modern journalism classroom is almost a replica of the typical Indian English newsroom.”

Recruitment to a mainstream firm comes with discriminatory screening at various levels and after being employed, marginalised groups such as women have continued to face problems like harassment at workplaces, threat of violence and intimidation and have been denied promotions at a given scheduled time.

Low salaries, fear of being laid off under unforeseen circumstances or discriminated against because of one’s social/economic/sexual/ethnic/religious/gendered identity are other serious threats to security and dignity that many underprivileged groups face when in corporate firms. Thus, a major reason that deters and discourages the marginalised to take up journalism as a profession in the first place is the private and capitalistic nature of the media outlets.

Why Representation of the Marginalised in Leadership Positions Matters?

Why the mainstream Indian newsroom has become a Brahminical space is because of the reality that Brahmins continue to be at the receiving end when it comes to access to professional prospects owing to reasons like their caste legacy and wide social circles plus contacts. Thus, aspirants from marginalised communities, even though being as or more competent and professional as their Brahmin peers, continue to be left out of the picture. This, all the more gives reason to why the representation of the marginalised in leadership positions becomes highly important to provide them with the social, occupational and economic mobility that they have been denied for decades, along with equally providing them with opportunities and recognition for their capabilities and work. Ideas of inclusion and self-determination of the underprivileged and marginalised voices in the mainstream can become fully meaningful only with them being relegated to positions of power that have otherwise been dominated by the ‘upper-caste-upper-class-cis-man’.

It is extremely important to understand that how much ever progress a Dalit or Adivasi makes in the context of rampant institutional subjugation and discrimination, this has an amplified generational impact on his/her/their entire community and family. Behind a dalit aiming for any occupational pursuit, lie the expectations and aspirations of several others who wish to gain similar dignity not only for their work but even their existence. Thus, one successful Dalit or Adivasi becomes an inspiration for several hundred others.

Before furthering the discourse around caste or gender related matters, it becomes highly imperative for the mainstream media firms who enjoy mass readership to introspect the institutionalised form of social segregation that they practice in their workspaces by not making enough room for the marginalised such that they too can take over leadership roles.

In opposition to the current mainstream Indian media firms that seem to be thwarted when it comes to committing to diverse representation, social media and smaller digital media outlets like Kashmir Walla, Dalit Camera, Velivada, Khabar Lahariya, TransVision, Adivasi Resurgence that are solely run under the leadership of marginalised identities seem to have started archiving the experiences of and atrocities against the marginalised while also giving voices to those who are systematically made absent from national newsrooms or positions of editorships of large newspapers and magazines. Before furthering the discourse around caste or gender-related matters, it becomes highly imperative for the mainstream media firms who enjoy mass readership to introspect the institutionalised form of social segregation that they practice in their workspaces by not making enough room for the marginalised such that they too can take over leadership roles.

References

- ‘Gender Inequality in Indian Media’, August 2019 Report by UN Women and Newslaundry

- ‘Who Tells Our Stories Matters: Representation of marginalised caste groups in Indian Newsrooms’, August 2019 Report by Oxfam and Newslaundry

- ‘Indian media wants Dalit news but not Dalit reporters’, by Sudipto Mondal for Al Jazeera

Featured Image Source: Feminism in India

About the author(s)

Nidhi is an undergraduate student, pursuing English Literature and Political Science from St. Stephen's College. She is someone who's trying to understand the ways in which intersectionality and feminist politics have been shaping her evolving thoughts and ideas. Her new found interests include reading Urdu Poetry, listening to folk music and blogging.

So you want reservation in News Broadcasting work? IN which part of the Indian nation are so-called Savarnas supposed to work? If they work in Govt anti-social casteist hate mongering websites like this have a problem, if they work in private sector, they have a problem. Who will then feed them? In which part of the constitution is the concocted word “Diversity” mentioned?