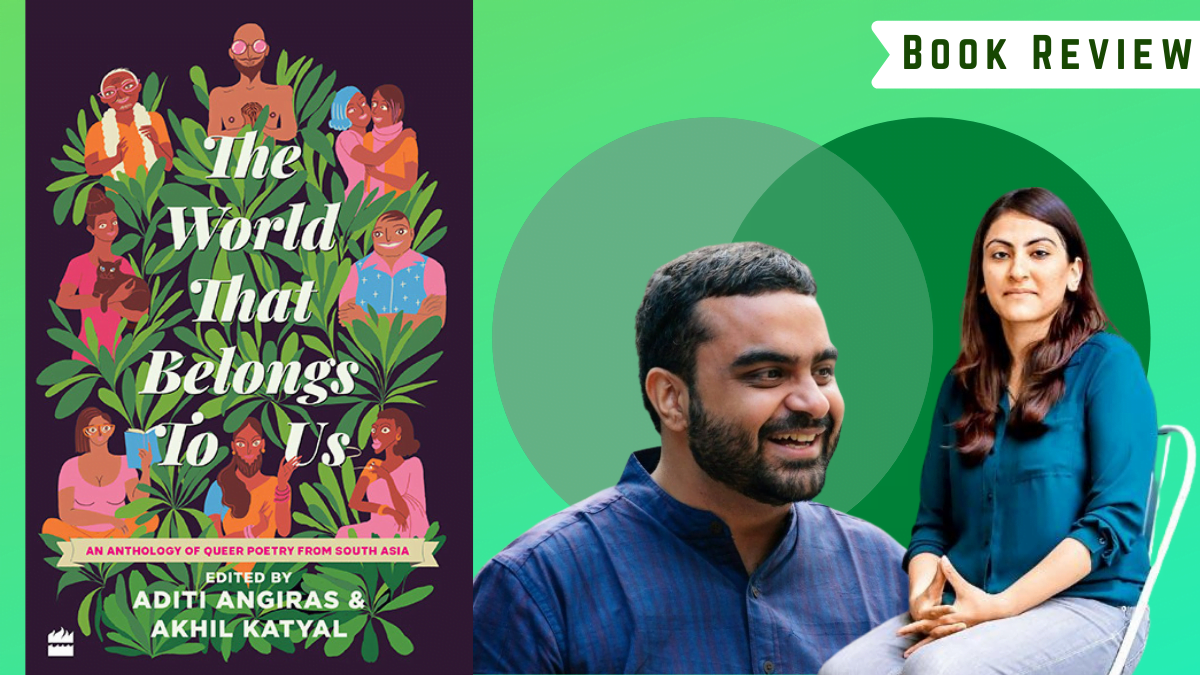

The World That Belongs To Us, as a first of its kind anthology, straddles two seemingly contradictory worlds— the world of identities as the premise for political articulation, and the non-identitarian, definition-eluding world of queerness. One might argue that the imagination and subsequent publication of an anthology like this derives from an identity-based political approach. However, as the editors, Aditi Angiras and Akhil Katyal note in the foreword, they let the word ‘queer’ “disperse” and how ‘queer’ “only pretends to signpost” an uncontainable range of names, identities and gestures. In the anthology, indeed, difference and identities manifest as heterogenous and in flux, and yet remain political in overt and subtle ways.

The anthology is also a grappling with the unwieldy, many-voiced category of South Asian poetry, and recognises how neither queer not South Asian can be spoken of in unitary terms. In the preface, the editors note how when Santa Khurai, a ‘nupi maanbi’ transgender activist and writer from the Manipur sent her poems, she requested to not be identified as Indian transwoman or a northeastern transwoman and to be described as an “indigenous Meetei transwoman from Manipur instead”, if the need arose. The anthology, thus, cognizantly does not intend to pile up South Asian queer voices, but attempts to present heterogenous and plural representations sitting next to each other in a collection of poems.

The World That Belongs To Us, as a first of its kind anthology, straddles two seemingly contradictory worlds— the world of identities as the premise for political articulation, and the non-identitarian, definition-eluding world of queerness.

The editors who ponder the question , “What is a queer poem?” in the preface, go on to anthologise a range of poems which cover themes of sexuality, protest and desire to less overtly straitjacketed and disembodied dimensions of queerness. Shals Mahajan writes, in a poem that articulates a distance from a fetishised narrative around queerness,

I swear I’d be kinky

and a dominant

if I exercised regularly

Joshua Muyiwa in a poem around registering desire calls his lover’s mouth “late February”, while Gee Semmalar speaks of borders and in potently ironic tones, critiques a romanticisation of globalisation, simultaneously imagining a “revolution of our people.” Well-known names like Ruth Vanita and Hoshang Merchant speak of things one wouldn’t necessarily suspect in an anthology of ‘queer’ poetry; as Vanita mulls over whether love is an elastic, or a fine, clinging fabric, while Merchant remembers his dead sister in a piquant poem that bristles with political anger and contemplates the “long, long time of” waiting. There is, thus, no necessary attempt to normativise queerness, while the collection does point towards the vastness of human experience that might be envisioned with it.

Also read: Book Review: The Lonely City By Olivia Laing

However, labels and categories are not wholly done away with in the face of no closed understanding of queerness, and strategic political awarenesses pervade throughout the anthology. Poems that deploy solid identities such as Mary Anne Mohanraj’s ‘After Pulse’ talk of “two men kissing” and speak of the violence non-heterosexual subjects have suffered, are part of this range. A number of poems implicate heteronormative establishments of varying sorts, and celebrate and articulate queer resistances.

However, The World That Belongs To Us is not simply political in its inception as an anthology of queer poetry, or because it carries poems that talk of rebellion and difference, but also because it attempts to traverse the poetic landscape of a region with complex histories and diverse literary cultures. A lot of poems, consequently, find themselves in translation in the anthology.

Among many translations by a number of people, Katyal translates Kushagra Adwaita’s poem as ‘We will be lost’ which ends with “to be lost is our Dhamma”. Dhamma, the untranslated word, which might be reductively understood as a cosmic law to be upheld, is a significant concept across religious and philosophical schools throughout the subcontinent and remains semantically untranslatable. The anthology also features an untranslated, bilingual Hinglish poem by Shakti Milan Sharma, reproduced in two scripts, which uninhibitedly speaks of a the peculiarities of a post-‘hook-up’ situation in an urban Indian location, where Hindi and English are used together colloquially. Translation and untranslatability, thus find themselves unseparated, which is also a hint towards how this anthology claims to have no all-knowing postures.

The World That Belongs To Us is not simply political in its inception as an anthology of queer poetry, or because it carries poems that talk of rebellion and difference, but also because it attempts to traverse the poetic landscape of a region with complex histories and diverse literary cultures.

The World That Belongs To Us, with all its diversity and consistent reiteration of humility, by the editors, self-secures itself from critique to a fair extent. However, for an anthology which is conscious of the kind of public it might create around itself, it does smack of editorial manoeuvres, which might possibly be inadvertent, to appeal to the anglophone press and the contemporary urban South Asian space. The translation of poems, and the selection of poetry, while intended towards heterogeneity, does end up seeming as tailored to appeal to a certain kind of reader in a certain sort of space. It does not necessarily disturb the liberal-urban status quo, in spaces where this anthology is likely to be read.

Also read: Book Review – Regretting Motherhood: A Study By Orna Donath

What is reassuring, however, is that the collection makes no tall promises of perfection and intends to provide the readers with something they would “cherish.” This, arguably, is the most endearing thing about the anthology, as the attempt is to not provide answers, but carve a relational space from where one can get glimpses into a world that belongs to “us”—people in the collection, and people outside it—a world that is vast and undefinable, but also a shared experience that cannot be domesticated.

It might be inferred that the point, perhaps, is to register difference, not homogenise it, and to see as much as one can from a certain vantage point. The World That Belongs To Us is a warm and valuable addition to such literary effort and a politically relevant collection that does not invest in homogeneity.

Abhinav Bhardwaj completed his undergraduate studies in English Literature at Hindu College, University of Delhi, earlier this year. A published poet and researcher, his areas of interest include world literatures and queer theory. You can find him on Instagram.

Nice post

Thank you for information