“Zameen kenkar? Jote oonkar!”

(Who owns the land? Those who till!)

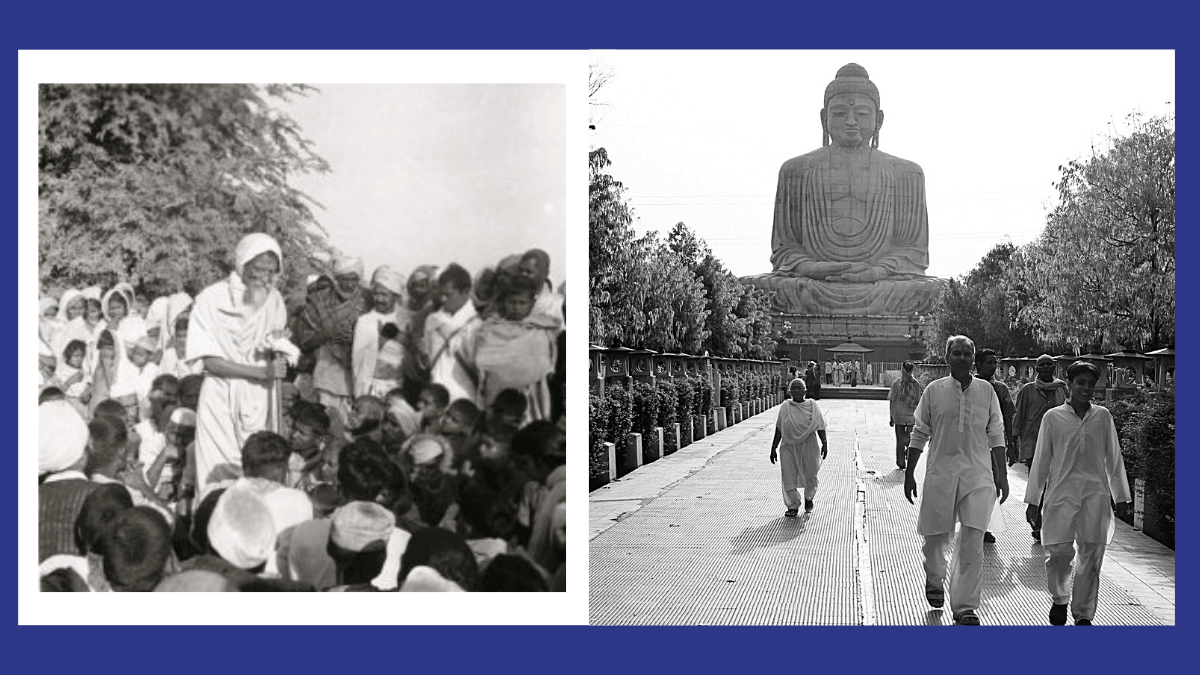

The revolutionary words that shook the throne of upper-caste dominance slyly perched on by the oppressive Mahants of Shankar Math, reverberated in the air of Bodhgaya—the land of spiritual and political revolution.

The Bodhgaya Land Movement, spearheaded by the socialist leader, J P Narayan, became the first non-violent rebellion to assert the land rights of Bahujan agricultural labourers that eventually brought the Brahmin priests to their knees. The first state to implement the Land Reforms Act (1950) and the Land Ceiling Act, 1961 had become riddled with priests amassing disproportionate assets. Years of caste violence, humiliation and economic exploitation of the landless Bhuiyan and Musahar castes ultimately drove them to the edge and thus, they came marching under the banner of Chhatra-Yuva Sangharsh Vahini (CYSV) to claim back the land that once belonged to them.

The first state to implement the Land Reforms Act (1950) and the Land Ceiling Act, 1961 had become riddled with priests amassing disproportionate assets. Years of caste violence, humiliation and economic exploitation of the landless Bhuiyan and Musahar castes ultimately drove them to the edge

The winters of 1978 Bihar were beginning to heat up at the sight of the first confrontation between the Maths’s Mahants and the labourers when they joined hands with Vahini student activists to guard the agricultural produce cultivated with their blood, sweat and backbreaking hard work. The young men and women of Vahini braved life-threatening assaults that came from the badly bruised egos of Mahants and their henchmen and courted arrests.

What started as a resistance against the bourgeoisie landowners who siphoned off the surplus yield and the influential religious figures who controlled the entire socio-economic and political scene of Gaya, evolved into a movement that brought the questions of caste, class and gender to the forefront. The rose-tinted picture of a jovial homogeneous farming community portrayed by the mainstream media came crumbling down as the more hideous image of India’s agricultural sector came to light. The rage in the hearts of the peasants and labourers was fueled by centuries of oppression practised by the upper-caste local leaders supported by the state machinery. Illegal usurping of land and benami (bogus) land transfers; furthering of caste hierarchies by the Panchayats; sexual and economic exploitation of Dalit women—the list was inexhaustible.

The pioneering social movement soon expanded its scope to engage women leaders championing for increased tenancy rights specifically for female agricultural labourers. The valorous Bahujan women were compelled to wage a two-pronged war against the upper-caste fief-holders as well as men from their own community. They understood the significance of land ownership that guarantees an individual a sense of financial independence and renders them eligible for availing farmer-centric schemes and loan waivers. Therefore, they insisted on separate deeds of land in their name. The demand sounded more bizarre to the men than it does now but determined to achieve what they set out for, the women did not step an inch back. Convinced about the sincerity of their cause, they resolutely pushed their demand which could free them of the shackles of caste and gender.

The heroic fight ultimately earned the unswerving Bahujans of Bodhgaya the rights to over 1,000 acres of fertile and well-irrigated land, of which 110 acres were registered specifically under the name of women.

“Aurat ke sahbhag bina, har badlav adhura hai!”

(Without women’s contribution, every struggle is incomplete)

The cries of Bahujan women, who constituted an overwhelming fraction of the struggle for equal land rights reflected their deep-seated agony. Antagonised not only by the exploitative dominant castes but also by the men of their own community, the women who had now found their voice contended against transferring the deeds of the redistributed lands in the names of men. The men who regularly indulged in alcohol abuse followed by domestic violence had become a nuisance for the women. The tedious routine of household chores beginning from the break of the dawn, back-breaking fieldwork, looking after the children along with other miscellaneous tasks throughout the day had started taking a toll on the women.

Exhausted under the patriarchal setup of work distribution that prescribed traditional gender roles and allowed limited economic autonomy, the women started insisting on their share of land. Having no ownership of land, widowed and deserted, women left alone to fend for themselves in a male-dominated society found it challenging to acquire a sense of financial and social security.

Also read: How Are The Recent Farmers’ Protests In India A Feminist Issue?

Learning at the education camps, ‘shivirs’ set up by the women activists daily, the women labourers acquired a critiquing lens that questioned the patriarchal notion of monogamy and the institution of marriage, the practice of patrilocal residence and on the other hand, promoted inter-caste marriages and women’s education. Heavily influenced by the feminist thinking of Vahini’s women activists Manjhar and Kunti, these women who sowed, irrigated, harvested and threshed the crops realised they formed an equally valuable component of the agricultural force and therefore, argued for an equal share in land rights.

Perplexed by the demands put forward by the women, the men activists criticised them for breaking the unity of the movement. Countering their criticism, the women proclaimed that the struggle was not merely about land but acquiring the means of production from their Brahmin oppressors that strengthens their power in society. However, if Dalit women face oppression by Dalit men, should the former not demand the same from the latter?

The men could finally see the rationale behind an apparently reactionary demand. Risking the chance of not obtaining the ownership of land altogether, the men supported their demand for land transfers solely in the women’s name. The Mazdoor-Kisaan Samiti stood by the women in front of administrative officers hesitant to break the tradition and rejected the proposal for joint titles in the name of the couple.

As a consequence of the dedicated fight kept alive by the Dalit women of Bodhgaya, the villages of Bija and Kusa fell in their lap.

The heroic fight ultimately earned the unswerving Bahujans of Bodhgaya the rights to over 1,000 acres of fertile and well-irrigated land, of which 110 acres were registered specifically under the name of women.

“Aurat, Harijan aur mazdoor, nahin rahenge ab majboor!”

(Women, Harijans and labourers will no longer be at the mercy of others!)

Four decades later, the Bhuiyan-Musahar castes of Gaya have returned to their traditional roles as farmhands on landlord’s soil, deprived of private land ownership. All that remains of the movement is a legacy of being the first-ever successful movement for land rights in South Asia. The land earned as a result of an indomitable fight put up by the men and women of Bodhgaya has circled its way back to the hands of upper-castes wealthy farmers and landlords yet again. The victorious Dalits who were awarded the land reclaimed by the Mahants found themselves incapable of managing the land.

Failing to arrange finances for irrigation and inputs to cultivate the land on their own, the farmers were crushed under mounting debts with exorbitantly high interest. The women too were forced to either mortgage their land to avail bank loans or sell their lands altogether. The eyes of Manjhar now reflect tiredness. The fiery student leader of yesteryear has made peace with the idea of joint titles of land in the name of the couple instead of separate land deeds for women. Thus came the tragic end to an incredibly inspiring story. However, the spark of revolution in the hearts of Dalits has not yet flickered out. As a local Musahar of Gaya sums it up,

“Revolution is inevitable. The dream of ‘Sampoorna Kranti’ will not go waste. It will take place. And this time, it will be irrepressible.”

Also read: Gorkhaland Movement: Have The Gorkhas Been Inclusive Of Their Minorities?

References

- A Field of One’s Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia, Agarwal Bina

- Agricultural Labour, Women And Land Rights In Bihar (India), Kelkar Govind

- Bodhgaya movement: Mahadalits Wait for ‘Acche Din’, Devendra Kumar

- Forward Press

About the author(s)

Deepshi Chowdhury is an eager political commentator struggling through her history honours course at LSR, Delhi. Painting revolutionary art and curating fusions of incompatible delicacies are her only two passions besides harbouring a penchant for articulating her meek dissenting voice through her mighty pen while listening to Faiz. Her words and portraits of Old Delhi's dilapidated doors are her only legacy.