“Tu cheez badi hai mast mast, tu cheez badi hai mast.” (You are a fun, fun, thing; you are a fun thing.) – Mohra (1994)

The classic Bollywood film is imprinted in our memories: the ones that promote stalking (eg. Anjaam), the ones that normalize harassment, and the ones that have beautiful item numbers that shamelessly portray women as nothing more than sexual objects.

Recently, I came across a project called the Headless Women of Hollywood which came as a shock: it shows how film posters have used hyper-sexualized fragmented bits of women to sell movies. Poster after poster was a headless woman whose identity was lost in the process of consumerism. What was important to the sale of the film was parts of her body, not her face. Apparently, a woman’s backside has more of a part to play in the movie than the woman herself.

Image Credit: Headless Women Of Hollywood

These pictures show us how even when the woman is not related to the plot of the film, a part of her body is used to further its sales. This is what is particularly important in looking at posters, for it is the means in which a movie is marketed, thereby is the method in which the consumers are reached out to (among others). When these consumers are reached out to by merely depicting naked women, it denotes a larger context of sexualization of women that is already being bought into, which is why marketing companies utilize such techniques.

It is telling of what people find most appealing in a movie. Women are fragmented and reduced to nothing more than their legs or breasts, portions of them sexualized to sell tickets. But herein lies the difference: when an industry promotes itself on the basis of women’s’ sexuality, it demeans them to a mere unimportant object in the film. The woman is no longer a person, but a mere means of marketing who is clad in swimwear or nothing at all.

One cannot help but wonder how Bollywood has behaved.

“Urre aa tenu ik gal samjhawan, maade purje nu kade hath main na paawan | Vaise taan mitran da bahut vadda score but white chicks na | I don’t like them anymore, bann mitran di whore | I mean mitran di ho.” – Honey Singh, Brown Rang

(Come here, let me explain something to you, I never touch anything sub-standard |By the way, I’ve scored many times, but only with white chicks | I don’t like them anymore, come be my whore | I mean be mine, ho.)

Sometimes we have to set Bollywood lyrics into our paradigms to remind ourselves of what we are dealing with, although Honey Singh will never fail us. To start off, I looked at the posters of popular films that grossed well at the box office: an indication that the viewership was extremely high and thereby the capacity of the movie to have a social influence.

Also Read: How Does Feminism Deal With Bollywood Item Numbers?

Pre-2000’s movies:

Adalat (1950)

The 1950’s featured Bollywood movie posters where women were looking away wistfully in distant wonderment of the days to come, a helpless damsel in distress who played the role of a “tamed” woman who helped the male protagonist. The concept was centered around the idea that women were ancillary tools in the movie, unimportant to be either in a sexualized display or dominant depiction.

Sujata (1960), Mughal-e-Azam (1960), Sholay (1975)

The 1960’s and 70’s were no better. The depiction of a helpless woman staring away wistfully forged on.

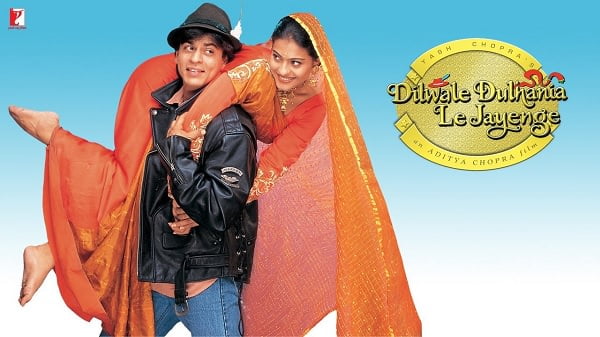

Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995)

The 1980’s–1990’s, though, were the worst time for women in the industry. An appropriate example is Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge where Shah Rukh Khan has Kajol thrown over his shoulders while he gleefully glances back at her. The idea of men “saving” women was prevalent in these movies, an easy propagation of the concept of men playing the dominant role, being forceful in their approach to wooing women.

Be Aabroo (1983)

It is here that we see movies centered around stalking, harassment, singing songs to a lady until she says yes, and dialogues like “Mard ko dard nahi hota” (Men do not get hurt) – Mard (1985) or “Agar khubsoorat ladki ko na chedo toh woh bhi toh uski beizzati hoti hai na” (If you do not tease a beautiful girl, then that is also disrespectful to her) – Maalamaal (1988). I’d beg to differ here but the ostensible damage has already been done. An entire generation of Indians grew up on the notion that if you persist long enough and learn enough song lyrics, any girl can be “scored”.

Judaai (1980), Hum Dil De Chuke Sanaam (1999)

For example, a common plot in movies is that if you prove your love to a woman using grand romantic gestures, even if she says no, she’s bound to come around eventually. The way an entire generation has learned to flirt is based on characters in movies who say these things, and that sets up a norm for acceptable behavior, pulling the bar lower and lower until this sort of problematic behavior begins to be viewed as normal. A woman walking around and being eve-teased is a trait commonly showed in movies, where the hero, who catches the glance of a beautiful woman passing him by, woos the girl he has set his sight on and follows her around while she walks away (Grand Masti). A cursory glance at these Bollywood movie posters will show the glaring trend mentioned earlier, the one of a helpless woman.

Aandhiyan (1952), Pyar Ke Naam Qurbaan (1990)

This generation also grew up with the notion that starting a brawl on the street while being chased and beating everybody up to defend the honor of a woman, is normal. It is this notion, the one that women must be “protected” that is inherently patriarchal in nature. Its underlying assumption is that the “weaker sex” is dependent on the “stronger” one to save them from, well, themselves. This sort of behavior being displayed by role-models such as actors leads to people imitating aspects of the movie characters they idolize. The newborn need to display how “macho” one is then leads to a larger sub-culture of violence in society. For example, taking matters into one’s own hands and “teaching the bad guys a lesson” instead of approaching authorities creates a subtext of vigilantism that, when let loose, is uncontrollable and unregulated.

Dhanwan (1981), Yaadgar (1984), Teri Bahon Main (1984)

The silver lining to the clouds of Bollywood was, however, that there was a point at which India was not afraid to showcase scenes with a sexual aspect to them. A comforting point to note was that Bollywood movie posters were unafraid to engage with sexuality.

Also Read: Stalking, Hypermasculinity, And Other Problematic Elements In Indian Cinema

Post 2000–2016:

Great Grand Masti (2016), Mastizaade (2016)

Here is where things got better for the image of women in Bollywood. For every item song and objectifying poster such as the ones displayed above, there were movies like Pink and Dangal that not only showcased women in lead roles but also marketed the movies without having to dissect women into sexual displays.

But even in these films, it is imperative that we critique the overall structures coming into play. While these movies do not objectify women, it places itself into the same narrative that oppresses women. The power structures in both Pink and Dangal are inherently problematic as they represent the “male savior complex”, a subliminal display of power where even the supposedly powerful female characters are shown as dependent on the males to come to their rescue. It is here that we must remember to never stop questioning these structures that are depicted to us, lest we begin to take them for granted.

Mujhse Shaadi Karogi (2004)

There are still areas in which Bollywood needs working: sexist movie dialogues, item songs and scenes normalising harassment. Brazen displays of harassment like Mujhse Shaadi Karogi certainly invoke a disappointed head nod, but fear not, there’s hope.

Kahaani (2012), Queen (2013), Neerja (2016)

For every Gandi Baat there will hopefully be more Queens with enthralling, fierce women with a drive of their own. The more we, the consumers, subscribe to movies with bold female characters, the more filmmakers will play into this demand. Movies play a vital role in shaping how an entire culture shapes itself, they provide a fantasy-based world which people strive to achieve, they set body standards for men and women (something “item numbers” fuel) and they influence our thought processes.

The sentiments generated by a movie can be strong enough to create a pro/anti-government sentiment, indicated by the government banning films that are “seditious” in nature for they have the power to alter people’s perceptions of the State. Films are medium of social change as they enhance the emotive processes of a person towards a particular issue, and once a person can identify with an issue and feel for it at a personal level, the probability of taking action/supporting the issue increases dramatically. For example, Taare Zameen Par was able to alter the way children with dyslexia were perceived, not as abnormalities of an evolutionary process, but people who are just as capable and normal as anybody else. Films have such a large influence that an Australian Court acquitted an Indian for the offence of stalking because he pleaded cultural context (Bollywood promoting stalking) as an excuse.

What is imperative for us to remember is that we are the consumer base for an entire industry that influences society. Promoters will reduce problematic content if protests erupt and people boycott their films, as the cash-flow will end. At this position of power, it is our responsibility to demand better standards and to demand that our movies do not promote harmful ideas.

If we stopped listening to songs that glorified harassment, promoters and singers would be forced to think up lyrics that are more conducive to their market. Why must it be so damn catchy, though? If we demanded that women get an equal share in the movies, beyond being mere plot-devices, those demands would have to be met.

Bollywood movie posters depict what we as a society subscribe to. As Bollywood moves towards a more positive depiction of its women, the urge to push it along must never fold. I know the struggle is hard to demand change, but it is worth it.

About the author(s)

Shilpa Prasad is a law student who loves books, poetry and her guitar.

The Mujhe Shaadi Karogi one has offended me for long. Someone finally articulated this issue. Thanks. Also, the poster of tiger zinda hai is also a small step in this direction.