The post-emergency political climate of India saw the rapid rise and fall of the Janata Party under Morarji Desai and the re-election of Mrs. Indira Gandhi as Prime Minister in 1980. The penultimate decade of the 20th century was witness to heightened political turmoil, with the assassination of Mrs. Gandhi in 1984, Rajiv Gandhi’s consequent election, and increase in popular support for the opposition, i.e., Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) resulting in a escalated sense of fear and vulnerability amongst minority groups and Muslims in particular. The latter would go on to be caught in the midst of the communal conflicts that would ensue consequent to the Hindu Right Wing’s rise to power.

In the midst of all the political conundrum, a significant development was to take place in the domain of personal laws, particularly the rights of Muslim women, and the inherent flaws in having a separate system of personal laws which had been in place in matters of marriage, inheritance and succession ever since the the Warren Hastings Plan of 1772. This was to come by way of the Supreme Court’s decision in Mohd. Ahmad Khan vs. Shah Bano Begum & Ors.

Also Read: All India Muslim Personal Law Board And The Circus Around Triple Talaq

History of the Case

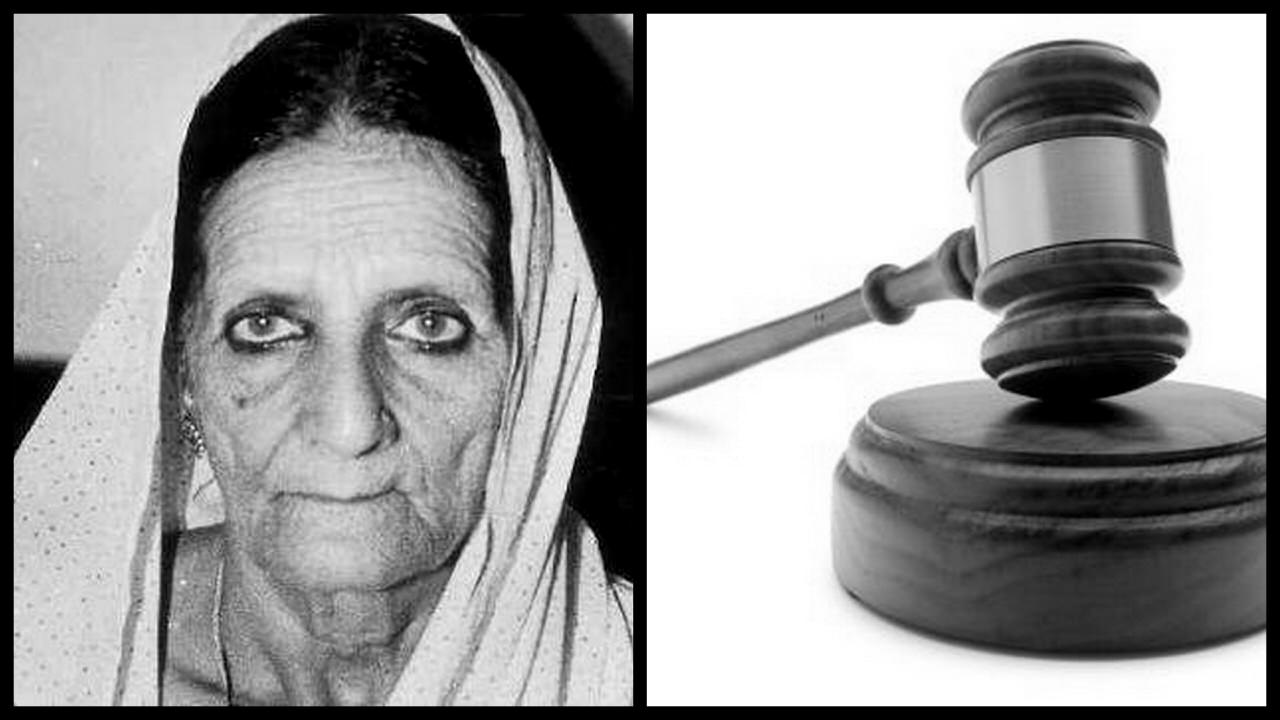

In April 1978, Shah Bano, a 62 year old Muslim woman, approached the court with an application claiming maintenance from her former husband, Mohammed Ahmed Khan who had divorced her by means of an irrevocable talaq in November in the same year. The two had been married in 1932 and had 3 sons and two daughters. Shah Bano had been living with her husband and his second wife before she was asked to move to a separate home in 1975.

Having been left with no financial support for herself and her 5 children, Shah Bano’s sought relief from the courts and her claim was based on the provision under Section 123 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 which imposes an obligation on a husband to provide for his wife, including a divorced wife, in case she is unable to provide for herself. The claim was contested by Mohammed Khan, an advocate by profession, on the ground that, the question of maintenance of wife pertained to matters of marriage and would consequently be governed by personal law. Thus, as per Muslim Personal Law, he was liable to maintain Shah Bano only for the period of iddat following the divorce.

The All India Muslim Personal Law Board supported Mohammed Ahmed Khan’s argument further intervening on his behalf to contend that Courts were not at liberty to interfere in matters which had already been covered by personal law, especially when arrangements had been made by Muslim communities to provide for and support divorced women by means of maintenance and mahr, for doing so would amount to violation of the Shariat Act, 1937, which categorically stated that in all matters of family, including divorce and maintenance, courts were to decide the questions in the light of the Shariat.

Also Read: Why Is The All India Muslim Personal Law Board’s Defence Of Triple Talaq Very Problematic?

What followed was a series of debates and decisions on the contesting interpretations of Sharia law and the rights of divorced Muslim women under the same. The case was finally decided at the appellate stage by the Supreme Court in 1985. The question before the apex court was whether the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 which were applicable to all Indian citizens, irrespective of their religion, would be applicable to the parties in the given case.

The Decision

The judgment in Shah Bano’s case was delivered by Justice Y.V. Chandrachud, the then Chief Justice of India on April 25th, 1985. The decision upheld the High Court’s decision to grant maintenance in favour of Shah Bano under the provisions of the Cr.PC, however increasing the quantum of maintenance. The decision took note of several debatable aspects surrounding the practice/regime of distinct personal laws, including the need for implementation of a Uniform Civil Code as provided for under Article 44 of the Constitution, and saw a departure from the Apex Court’s traditional interpretation of personal laws, recognising the conflict between the need for gender equality and perseverance of religious principles, and adapting a more inclusive and egalitarian interpretation of Muslim Personal Law.

“Section 125 was enacted in order to provide a quick and summary remedy to a class of persons who are unable to maintain themselves. What difference would it then make as to what is the religion professed by the neglected wife, child or parent? Neglect by a person of sufficient means to maintain these and the inability of these persons to maintain themselves are the objective criteria which determine the applicability of section 125. Such provisions, which are essentially of a prophylactic nature, cut across the barriers of religion. The liability imposed by section 125 to maintain close relatives who are indigent is founded upon the individual’s obligation to the society to prevent vagrancy and destitution. That is the moral edict of the law and morality cannot be clubbed with religion.”

– Justice Y.V. Chandrachud – Mohammed Ahmed Khan Vs. Shah Bano Begum & Ors.

Post Shah Bano

The decision drew severe criticism from the conservative groups within Muslim community. A bench of five Hindu judges delivering a verdict on competing interpretations of verses of the Holy Quran and critiquing the principles of Islam, with the judgment going to the extent of saying that the degradation of women was the fatal point of Islam, was only to add to the communal tension, given the political environment surrounding the decision.

Giving in to the mounting pressure from conservative forces, in what was both an attempt to undo the after effect of the ruling in Shah Bano’s case and appease the Muslim community, as well as suppress the growing atmosphere of discontent and counter pressures, the Congress Government, which under the leadership of Rajiv Gandhi had come to power in 1984, felt a need to pacify the masses and accordingly passed the Muslim Women (Protection on Divorce Act), 1986.

The Act, in effect overturned the decision in Shah Bano’s case providing that a husband was bound by law to pay maintenance to a divorced wife only for the period of iddat, following which, in case the woman was unable to provide for herself, or did not have relatives to support her, the magistrate could direct the Wakf Board to provide her with sufficient means of sustenance for herself and her dependent children, if any. The Act was received particularly well by conservative fundamentalists. On the contrary, it was critiqued for having defeated the cause of the rights of Muslim women that had been brought forth in Shah Bano’s case, thus relegating them to a subordinate position within the domain of the personal, the attempts for gender equality being suppressed in favour of communal harmony.

(The Constitutional validity of the Act was challenged by Shah Bano’s Lawyer Danial Latifi and upholding the validity of the Act, the Supreme Court observed that the liability of the husband to pay maintenance under the Act was not limited to the iddat period.)

The Importance Of The Decision

The decision in Shah Bano according the protection of Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 to Muslim women, despite attempts having been made to render it futile, is seen as a landmark decision in the domain of social and legal history of India. Though the decision was not the first to recognise Muslim women’s rights to maintenance under Section 125, it was particularly significant in the context of the conflicting claims of gender justice within personal laws and the need to strike a balance between the conflicting religious and cultural claims to bring them in conformity with the ideal of equality, gender equality in particular.

It granted recognition to legitimate claims for equality and equal treatment of Muslim women in matters pertaining to marriage. The aftermath of the decision had far reaching consequences. It resulted in the filing of a number applications for maintenance by divorced Muslim women, further questioned the role of families and communities as protective institutions. The decision was a milestone in the quest for justice by women within the institution of families, of Muslim women in particular.

Ironically, owing to pressure from the community, Shah Bano herself withdrew her claim for maintenance, a fact which is illustrative of the repeated instances failed pursuits of gender justice owing to preserving the rights and interests of communities. On the other hand, the debates following the decision used the question of rights of Muslim women as a tool for gaining political favour, which in turn undermined the question of equality, emphasis shifting that of secularism. The Congress having resorted to the policy of appeasement, the BJP saw the decision in Shah Bano’s case as an opportunity to stir up communal politics.

The Shah Bano judgment remains significantly relevant, particularly in the present day context, when the question of Triple Talaq under Muslim Law has been gaining focus in discourse on gender inequality. In the struggle between preservation of religious and cultural principles and the quest for gender justice, the latter tends to be compromised to yield to the demands of the former.

Also Read: BMMA Co-Founder Zakia Soman On The Need To Reform Muslim Personal Law

About the author(s)

Graduate from Lady Sri Ram College & Faculty of Law, University of Delhi. Currently working as a Law Researcher at the High Court Of Delhi.

a small error,itss section 125 and not sec 123 of crpc