The phenomenon of asceticism in Hinduism is often regarded as the essential feature of the religious doctrine. Contrary to popular belief asceticism and religion are not synonymous with each other. The ascetic tradition is an embodiment in a person rather than a doctrine. Interestingly, this embodiment is understood as a manifestation solely in males and not in females. The discourse on asceticism in Hinduism allows both sexes to follow the path to attain Moksha or liberation. However, the difference becomes obvious when a female ascetic is given the status of an ‘outsider’ and the male that of an ‘insider’.

The non-conforming, non-familial, non-normative female ascetic thus, remains an invisible being in an overwhelming masculine world of asceticism, where women fight taboos to create a space for the woman as an ascetic.

The non-conforming, non-familial, non-normative female ascetic thus, remains an invisible being.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, there have been debates amongst scholars on the topic of alternative subjectivities regarding which are the notion of revolutionary identities in mainstream discourse. Female asceticism is one such ‘rebel’ identity. However, the question which may arise in many ascetics as well as non-ascetics is — ‘Can a woman be a legitimate ascetic?‘ Yes, she can, but in terms of orthodox religious doctrine, she can become an ascetic only if her renunciation of the domestic realm is accomplished.

In simpler words, Hinduism has always been focused around the upper castes, the Brahmins, and to some extent on the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas. The contradictory nature of Hinduism reveals its misogynous inclinations by limiting renunciation to the Dwij or the twice born man. It is important to note, that the twice born man has the freedom of choice between two modes of life — the householder, and the renouncer. But, for women, only a single mode of life has been prescribed — marital life.

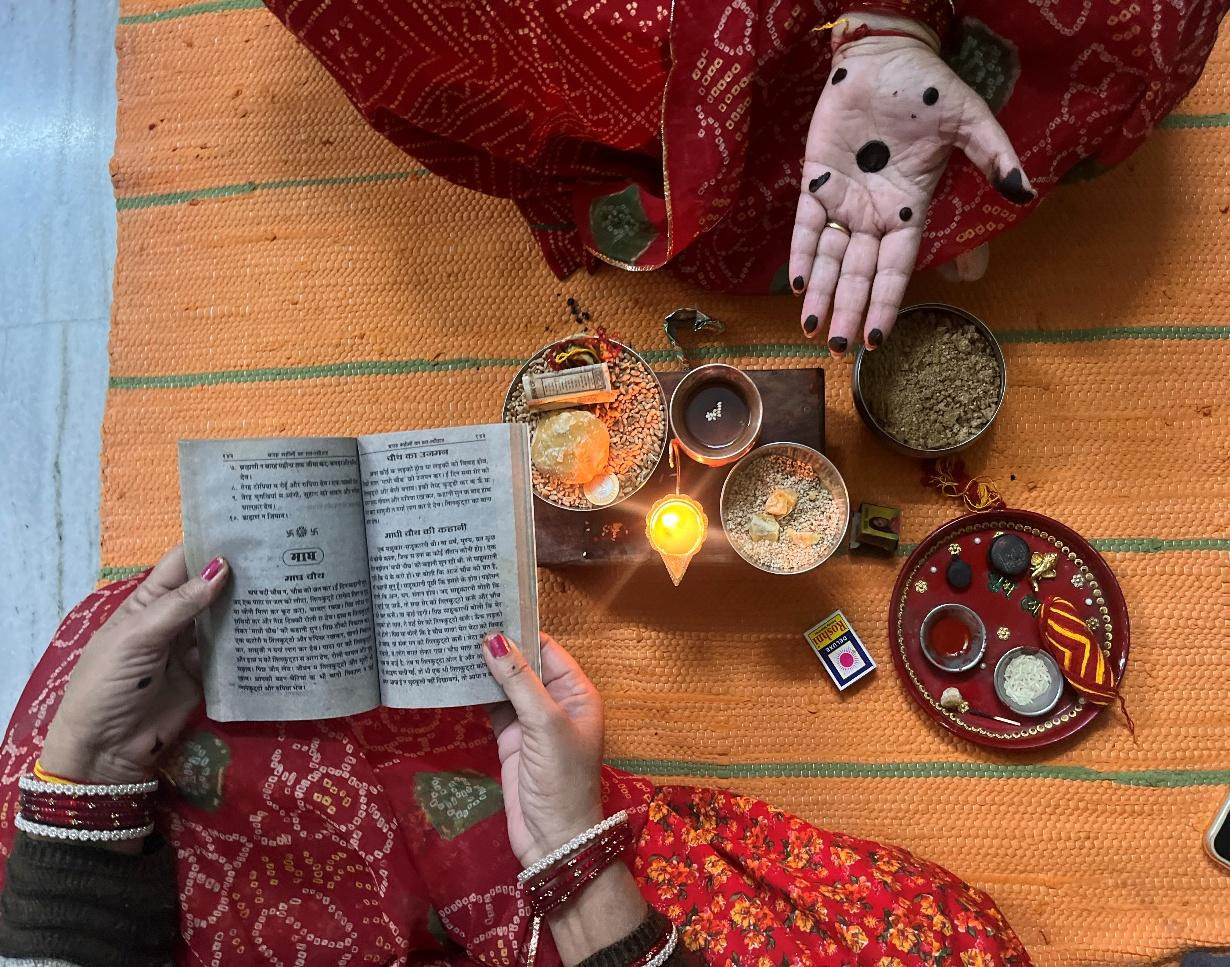

Such a mechanism of exclusion in Brahmanic orthodoxy operates on the principle of menstruation — perceived as ‘impure’ and ‘sickly’ by Vedic literature. As a result, women are believed to be innately lacking the ‘natural’ tendency towards achieving Dharma (religious duty), and so they must follow a series of rituals and ceremonies in order to gravitate towards a ‘state of purity’. Such notions of purity and pollution form the foundations of gender relations in the ascetic tradition, thereby making the female ascetic invisible in society.

This mechanism of exclusion in Brahmanic orthodoxy operates on the principle of menstruation — perceived as ‘impure’.

With so much patriarchal discrimination in the ascetic tradition, I wonder, why do women become ascetics in the first place? Or what kind of women may become ascetics? Sociology and anthropology suggests that women adopt an ascetic lifestyle upon becoming widows, in order to escape the social stigma attached to widowhood imposed by sectarian chauvinism. Others believe asceticism is a path adopted by these women to escape the inevitable condition of beggary after the death of their immediate family members, most importantly, their husbands.

Also Read: The Bhakti Movement and Roots of Indian Feminism

There are some young renouncers who are submitted the responsibility of the care of a group of pious women since their families cannot afford dowries. In such situations, young girls meet their gurus in ashrams, who then initiate unmarried young girls into their sect and take them under her/his service.

For a woman to become an ascetic, is to question the ascribed cultural norms laid out for her. Attempting to step outside this normative structure gives the female ascetic the status of an ‘outsider’. This is because she has not only chosen to adopt a certain way of life, a life which is primarily prescribed for males, but has also chosen to be critical of, and to question the existing social order. This ‘deviance’ in ascribed gender norms (as Brahmanical orthodoxy would call it), is perceived as a threat to the existing power structure which gives privilege to male ascetics. As a result, there is no surprise that male ascetics would protest against women being ascetics at all.

When it comes to asceticism, the initiation ceremonies mark the separation of a woman from her householder duties. These initiation rituals release women from their previous social identity, which at times can involve shedding of various identity markers that help people to identify one’s social role and status. Feminist artist and activist Sheba Chhachhi in her work ‘Ganga’s Daughters’ (1990) traces the transformation of ordinary women into ascetics as they part with their clothes, hair, name, caste, and familial relations. In search of Moksha, these women embrace their new ascetic identity. An identity, in which they are no longer anybody’s parents, sisters, or wives.

these women embrace their new ascetic identity – in which they are no longer anybody’s parents, sisters, or wives.

That being said, the life of a woman ascetic in Hinduism is under appreciated, and holds a complicated position. As they step out of the orthodox Brahmanical system of surveillance into newly formed identities as ascetics, women are perceived as beings who have conquered their right to be granted individual freedom. It’s almost as if women have been reincarnated into different beings after performing the last sacrifice of their prior identities.

As a result of these women’s sense of self, their new found identity can be understood as a way of creating a new space within the folds of the Hindu religious doctrine. It is truly extraordinary to see how these women courageously defy traditional gender norms, and carry a will force to raise themselves to the level of their male ascetic counterparts.

Featured Image Credit: Bhaskar.com

About the author(s)

Stuti holds a master's degree in Sociology, and is currently pursuing her M.Phil in Sociology from Mumbai University. Her areas of interest include gender studies, art history, culture and Identity, and, critical studies of science and technology. Her blog (stutikakar.com) reflects her interest in contemporary debates.

Your article is describing the state of a problem as it was some 1500 years ago. The situation regarding women is different now. In the earliest period , that is Vedic society had this division of two paths, the householder ritualistic and the ascetic yogi who denounced ritual.

The householder engages with desire however moderates his consumption according to scriptural and social laws. The ascetic avoids desire altogether.

This is what you are describing but this situation changed from 500 AD onwards with the emergence of the non-Vedic tantric revelations.

The tanatras showed that one did not need to escape desire to achieve enlightenment, rather one needs to understand what desire is. By understanding desire we gain the ability to transmute it from the limited desire of an individual being to the unlimited desire of the entire cosmos, and thereby we liberate ourselves. Essentially tantra made asceticism redundant.

In tantra women were worshipped and they were all powerful. Why would they take the inferior path of the ascetic?

As a tangent I will mention that there are many existing male dominated ascetic schools today such as the dashanami groups. Interestingly they don’t follow a pure ascetic practice. Shankaracharya realised that there was a practical gap between ascetic technologies and his metaphysical conception of Brahman as the ultimate state. He realised the had no explanation of Shakti tattva, thus he added some tantric rituals of the srividya tradition to the schools he formed.

Basically they try to use the power of shakti without acknowledging that desire is shakti and without ascribing to shakti her metaphysical role in manifesting the universe. They are part time tantrics and because they engage in tantra without breaking ascetic purity or their caste, they do not get full results of the tantric method.

If you believe shakti to be limited then that is how she will manifest for you.

Thus there has been a consistent criticism of these ascetic-tantric groups from the popular pure tantrism. See kabir, Lalon or abhinavagupta….