Bhakti as a concept means devotion and surrender. Originating from South India in the 7th century, the Bhakti movement propagated the idea that God dwells in each individual and one could attain God through faith and devotion. Earlier historians perceived the Bhakti movement as a literary or at best an ideological phenomenon which had religion at the basis of its inspiration. But later it also came to be regarded as an attempt at bringing about an egalitarian society, or as a protest against Brahmanical monopoly.

With everyone equal in the eyes of God, the movement brought religion and spirituality to the marginalized classes, specifically women, whose religious expression was restricted in many ways. It was a movement that not only aimed at individual salvation and a mystical union with God but also towards socio-religious egalitarianism. It liberated both God and man (inclusive of woman) from the shackles of Brahminical monopoly. The movement created a space where one could have a personal relationship with God and removed all intermediaries, rendering all Brahminical traditions and the role of Brahmin priests futile.

With such an alternative religious system in place, many women and lower-caste individuals joined the movement and expressed themselves with no inhibitions. The quest for salvation no longer required Sanskrit mantras and rituals, but included the dignity of labour.

The movement saw several women saints as well as saints from lower castes leading masses in their regions, and singing songs and poems in their vernacular language. The Bhakti movement was not just one movement, but an accretion of smaller regional movements towards salvation and against oppressive hierarchies.

Bhakti saints rejected all fixities to religion and spirituality. When temples closed their doors on them, they, freeing their god from closed doors, carried him in their hearts; they either discouraged idol worship and worshipped a nirguna (formless) god or substituted him as one of those who could dwell in humble abodes.

Bhaktins: Pioneers of Feminism in India

Tracing the roots of Indian Feminism led us to women in Bhakti, who challenged Brahminical patriarchy through their songs, poems and ways of life. At a time when most spaces were restricted to women, they embraced Bhakti to define their truths to reform society, polity, relationships and religions. They broke all societal rules and stereotypes, and lived their lives as they pleased.

“In the Bhakti movements, women take on the qualities that men traditionally have. They break the rules of Manu that forbid them to do so. A respectable woman is not, for instance, allowed to live by herself or outdoors, or refuse sex to her husband- but women saints wander and travel alone, give up husband, children and family.” – A.K. Ramanujan, ‘Talking to God’

Women saints wrote poems and songs expressing their love for God, who is their lover, husband or consort, and about their oppression and desires for freedom. They not only challenged the god-like status of their husbands, but also gave up their motherhood and family. In this aspect, Bhakti meant different things to women and men. While a male bhakta could follow his chosen path and remain a householder, this was not possible for the women. Most women had to choose between their Bhakti and their married and domestic life. Many of these women could proceed on their chosen path only by discarding their marital ties altogether.

Mirabai, a Bhakti poet of the 15th century and a Rajput princess, denied the legitimacy of her marriage to Raja Bhojraj and refused to consummate it. She embraced Lord Krishna and spent hours at the temple worshipping him. Roughly a decade into their unconsummated marriage, Bhojraj died. Just as Mira had refused to be his wife, she also repudiated the role as his widow. She would neither wear the mourning garb nor follow any of the customs expected of a royal woman grieving a lost husband. Mira is a fortifying precedent of a woman who refused to be cowed. She has lived through the ages through her songs and poems, describing her utmost devotion and love towards Lord Krishna.

In addition to contending with male dominance, Bhakti women also had to bypass gender rigidities. Ramanujan lists the strategies women undertook for the same: refusing marriage to a mortal; becoming a courtesan; miraculously skipping youth; walking out of marriage, becoming a man or an old ugly woman; refusing widowhood norms; refusing motherhood; walking naked; or breaking caste barriers. Hence, the experiences of men and women Bhaktas were starkly contrasted.

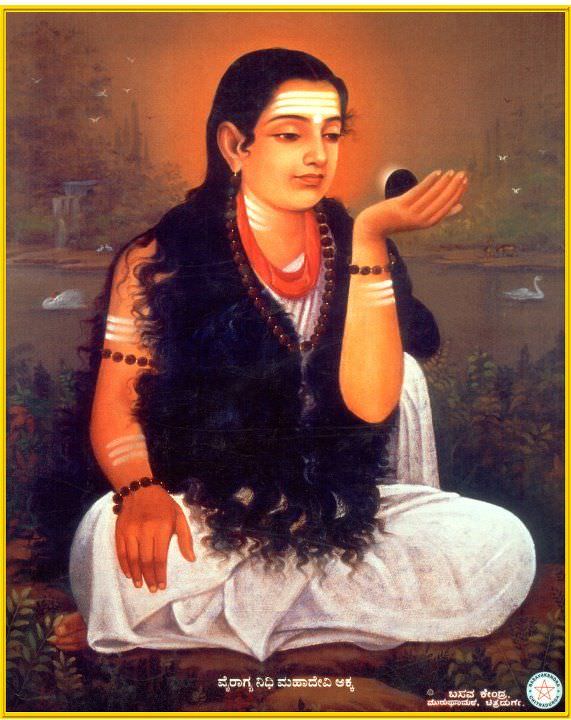

The nakedness of the female body was also perceived as a great threat to men, and heavily condemned by the larger society, and still is. However, women Bhakti saints like Akka Mahadevi and Lal Ded challenged these norms. Akka Mahadevi walked out of her marriage and wandered naked, with her body covered only by her hair. She wrote in her vachana:

“To the shameless girl

Wearing Mallikarjuna’s light, you fool

Where is the need for cover and jewel?”

Commenting on her own nakedness, she writes:

“People,

male and female,

blush when a cloth covering their shame

comes looseWhen the lord of lives

lives drowned without a face

in the world, how can you be modest?When all the world is the eye of the lord,

onlooking everywhere, what can you

cover and conceal?”

Lal Ded, one of the earliest Kashmiri mystic poets also refused to stay confined to domestic tyranny and its power hierarchy. She left her home, broke all material ties and wandered unclothed in search of God. In her verses, she also expressed her anguish towards the Brahminical code:

“Your idol is stone, your temple a stone too-

All a stone bound together from top to toe!

What is it you worship, you dense Brahmin?

Bind but the vital air from heart to mind.” (Mattoo 334)

On the other hand, Sant Soyarabai neither rejected marriage nor overtly defied societal norms. She wrote about her family, daily existence and her devotion to god Vithoba, pilgrimage to Pandharpur, married life and finding freedom amidst it. Her abhangas to the misery of daily life and restrictions to which they were subjected as belonging to the Mahar caste indicate her heightened caste and gender consciousness.

Medieval India had an atmosphere of immense discrimination, with patriarchy held in the highest regard. Hence, women sought Bhakti to move out of the restricted domestic spaces and oppose patriarchy and Brahminical hegemony. The rejection of the power of the male figure that they were tied to in subordinate relationships became the terrain for struggle, self-assertion and alternative seeking.

Bhakti women laid the roots of feminism in India. With sheer bravery, tenacity and their devotion to God, they created an autonomous space for themselves and refused to be tied down by societal norms. They did the unspeakable and displayed the true strength of a woman’s spirit. They created their path to freedom and inspired many others to follow their own will. They transcended the social identities and material realities into a universal spiritual realm.

References

- “Indigenous Roots of Feminism: Culture, Subjectivity and Agency” By Jasbir Jain

- “Divine Sounds from the Heart— Singing Unfettered in their Own Voices: The Bhakti Movement and its Women Saints (12th to 17th Century)” By Rekha Pande

“Rebels, Mystics or Housewives? women in Virasaivism” By Vijaya Ramaswamy

“A search for Feminist roots” By Romit Chowdhury

“Mirabai and her Contributions to the Bhakti Movement” By S.M. Pandey and Norman Zide

About the author(s)

Anime enthusiast. Photographer-in-progress. Kimchi Addict. But, Feminist first.

Thanks for writing this article. 🙂 Do you have any recommendations for reading the work of Lal Ded? I have read a few poems from her and I find her as enchanting as Kabir.

So Beautiful! 🙂

Nice ☺️