“My name is Camila Canicoba and I represent the department of Lima. My measurements are: 2,202 cases of femicide reported in the last nine years in my country.”

Miss Peru 2018 and the world watching it, witnessed an unusual event when all the contestants instead of giving their body measurements, provided the statistics of gendered violence against women in their country.

In an industry that (mostly) profits from creating wax-like, solid, unperturbed-by-reality images of women (and men alike) to be the alpha representatives of the human body, stepping outside the periphery to express the problems plaguing the citizens of this world instead of giving a calculated account of your “measurements”, becomes an act of resistance.

It was just two weeks ago when I was discussing the normative beauty standards with someone, who happened to share my discomfort when we both saw how in a television show, “hunting” for female models, women were criticized for being too thin, too fat, too this, too that. “In many International Beauty Pageants, women who are too thin are banned from participating”, said one judge who was visibly “worried” about a female contestant who had actually been thin all her life.

Image credit: Dekhnews

While I was researching for this article, I found how in many critiques, the “Indian-ness” of these pageants was questioned. What does an Indian woman look like? Do all of them identify themselves with the contestants when they watch the annual pageants on television? How is the “Indian” woman conceived in these pageants, really?

An aspiring candidate of Miss India who must be an Indian national, should be at least 5’5” inches tall, must have the “traits of a female”, should never have “embraced motherhood”, among other things. Let’s keep our shared sense of “WTF” aside to interrogate how there is no mention of skin colour, body type/size in these terms and conditions.

So does that mean any woman who meets the assigned “criteria”, but who does not have the “ideal” body type or skin colour can participate? I think, yes. But how long before it is pointed out to them? How long before she has to count her carbs and appear confident each time her worth is calculated in terms of how many kilos she weighs or if she is fair enough?

Also Read: Beauty Standards – The Ugliest Trick Of Patriarchy

When Miss Peru contestants defied the norm of giving out their body measurements, they not only shifted the discourse to the constant violation of human rights of women through the violence they are subjected to, but also to the social construction of a woman based on what her “size” is. This subversion is located in the larger sphere of shifting the gaze to the everyday reality of all women who are surviving off of the fear of the many forms of violence that they are at the receiving end of; and how many of them have to constantly battle with physical and mental health issues because of unrealistic body standards imposed on them.

What is this obsession over “one type” of a woman in Indian Beauty Pageants? The figure of a woman, in such pageants, becomes a site of “catering” to the male gaze because that is the only gaze that matters in a patriarchal society. It becomes a site to look up to for other women to match, a site of controlling women. Look at it very simply, how does one’s skin colour get attached to the kind of clothes (or more specifically, the colour of the clothes) one can wear?

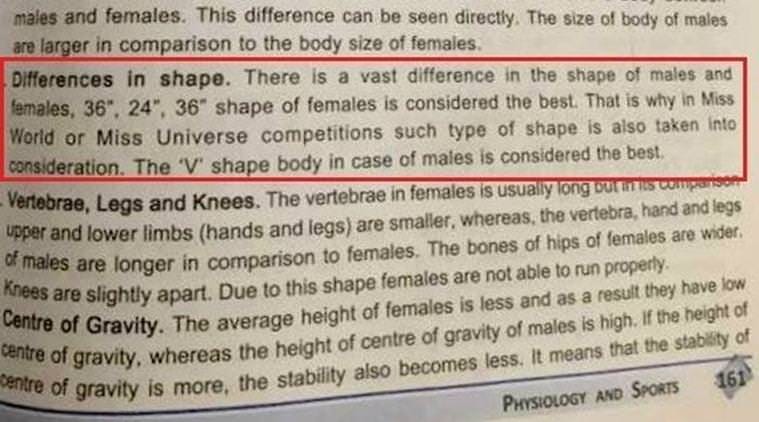

Taking pride in India being a land of diversity is stupid if you are still hungover by the “36-24-36” (and similar confining) body images. This reminds of the case of an Indian physical education textbook which gives examples of Indian Beauty pageants to reiterate how the 36”24”36” figure is ideal for women which can be achieved through sports. Let that sink in, if it does at all.

Taking pride in India being a land of diversity is stupid if you are still hungover by the “36-24-36” body image.

The exclusionary, stereotypical, and highly patriarchal nature of these pageants is reflected each time they air. In that context, Miss Peru 2018 stands out as exceptional.

However, the long drawn debates of Indian Beauty Pageants being a source of empowerment are important to be looked into. Whose empowerment are you really speaking of? Who is the target audience that can assess, review, or be affected by your display of empowerment?

The situation is bleak, undoubtedly. But when I read about pageants like Miss Trans Queen India, a beauty pageant for transgender community held in April this year, I cannot help but complicate the narrative more. It is not just the representation of the community that is brought forth by such initiatives, but also a way to shatter normative beauty standards that have, surprisingly, stood the tests of evolution.

Image credit: The Better India

We are all different. Recognition and promotion of only one type of individuals isn’t what we need. You cannot keep narrowing your definition of how a woman should look like only to call your efforts of giving “platforms” of representation as spheres for all women to identify with. The elitist nature of these pageants is hard to miss. This is the time when we, like the Peru contestants, stand up to further discourses of beauty, of gender based violence, of women issues, of difference. Let this be the lead we need to be inclusive.

Also Read: My Experience With Beauty Standards In The Trans Community

Featured Image Credit: The Daily Edge

About the author(s)

Pursuing master's in Gender, Culture and Development, she is a hoarder of stationery and stories and likes to believe she has that one story to tell that is her own. When she isn't searching for good coffee or reading about feminism and gender, she likes to binge on sleeping.

Taking pride in India being a land of diversity is stupid if you are still hungover by the “36-24-36” body image.

Taking pride in India being a land of diversity is stupid if you are still hungover by the “36-24-36” body image.