In 2014 a young PhD in Philosophy, ‘W’ was offered a much-coveted tenure-track faculty position in a small college in the USA. Finding a tenure-track academic position in a job market saturated with freshly minted doctorates is akin to finding the proverbial pot of gold at the end of the rainbow but W’s joy was short-lived.

When she attempted to negotiate a higher starting salary, maternity leave and research support, the college withdrew their offer, suggesting that W’s expectations did not fit the realities of a small teaching institution. The story sent ripples across academia with some seasoned professors describing her actions as thoughtless and arrogant and others suggesting that the response of the college had been high-handed, perhaps even unethical. What everyone agreed, however, was that negotiating the terms of employment is an extremely tricky exercise, especially for women.

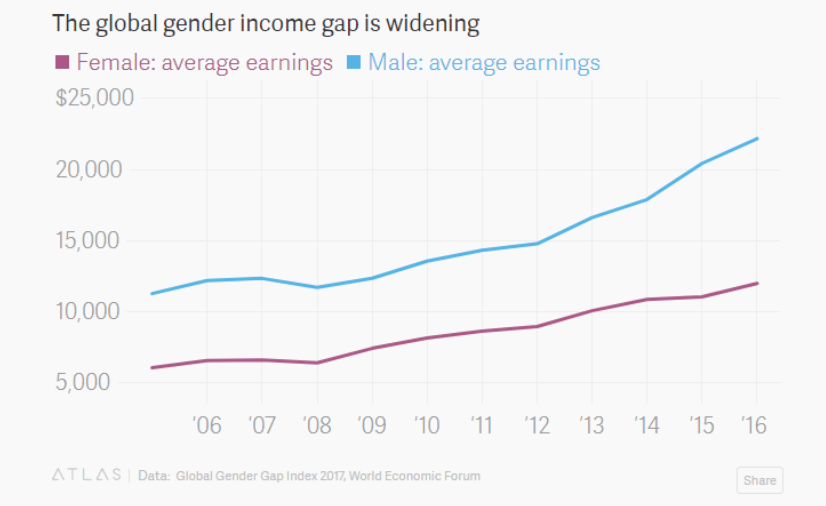

Source: World Economic Forum

As the graph above indicates, the wage gap between men and women across the world has been increasing over the last decade. The Global Gender Gap Report of 2017 found that on an average, women across the world earn about 57% of men’s earnings, a situation that is unlikely to change for the next two hundred years unless drastic efforts are made to remedy the situation.

In India, rural women workers earn about 78% and urban women earn about 75% of what their male peers earn* according to the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO, 68th Round, 2012). But India’s better performance compared to the global average is not necessarily cause for celebration given that recent years have seen a decline in women’s workforce participation.

In her article on Feminism in India, Mudra Mukesh discusses several reasons for the wage gap including the tendency to promote men to supervisory positions and women’s failure to negotiate wages. Another major factor is employers’ erroneous belief that women earn ‘pocket money’. I found this to be the case in my research on women employed in the IT industry and in school teaching in India.

on an average, women across the world earn about 57% of men’s earnings.

I also found that while most women contribute to household expenses, children’s education and investments for family’s future security, few negotiate their salaries, rightly surmising that proactive negotiation has a ‘social cost’. Private school teachers found that negotiating wages earned them the label of ‘trouble-makers’ with management.

When women engage competently and confidently in negotiations, particularly in job interviews, they violate the norms associated with their gender identity and risk being labelled as aloof and self-serving, thereby threatening collegiality. Through a series of experiments Hannah Bowles, senior lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School, and her colleagues, Linda Babcock and Lei Lai found that both men and women tend to be wary of working with women who negotiate for higher wages while showing no negative reaction to men who engage in similar behaviour.

Stereotypical gender norms require women to be other-directed rather than individualistic, compliant rather than assertive and collaborative rather than competitive. Gender bias researchers such as Iris Bohnet and Andrea Schneider argue that in professional life women often need to make a trade-off between perceptions of likeability and competence i.e. women who are perceived as capable are likely to be unpopular while women who are popular are believed to lack capability.

However, there are some circumstances under which women’s engagement in negotiation is accepted, even welcomed. Andrea Schneider, of Marquette University Law School, studied peer evaluations of both male and female lawyers and found that the women’s competence as negotiators did not have a negative impact on their likeability vis-à-vis men.

Also Read: Where Do Women Figure In The Indian Economy?

Schneider argues that this contrary trend could be attributed to the importance given to negotiation skills within the legal profession. Female lawyers who are good negotiators act within professional norms even if they violate gender norms. Furthermore, she argues, in ‘high-status professions’, deviance from gender stereotypes tends to be forgiven more easily than in ‘low-status professions’.

This is a depressing thought for the large number of us who are concentrated in so-called ‘low-status professions’ but all is not lost. Both Bowles and Schneider suggest strategies that women can deploy in negotiations particularly as they relate to wages, although it is noteworthy that none of their strategies challenge existing gender norms. With that important caveat here are a few:

- Find out what your peers make. In their book, Women Don’t Ask, Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever argue that women negotiate more successfully when there’s less ambiguity about pay scales i.e. knowledge is power.

- Use relational language: ‘We’ rather than ‘I’. Controversial ‘Lean In’ Author Sheryl Sandberg recounts that when negotiating the terms of her employment as Facebook’s Chief Financial Officer, she reminded her prospective bosses that negotiation was a key skill expected of someone in her role. This is akin to what Schneider calls providing a ‘social account of one’s assertive behaviour’: suggesting that there are good (collectivist) reasons for being demanding.

- Share your concerns that the negotiation might affect your future relationships (without labouring the point or being apologetic).

- Show that you can be flexible about how your demands are met.

- Justify the request in terms of previous accomplishments, tangible contributions, skills and experiences that you bring to the job.

Private school teachers found that negotiating wages earned them the label of ‘trouble-makers’ with management.

Unfortunately, none of these strategies are fool-proof, as W found out. While it’s great to empower women with the knowledge and training to negotiate, it’s unfair and, as Iris Bohnet suggests, counterproductive to expect them to bear the burden of doing so alone. Systemic changes are essential to narrowing the gender wage gap, including:

- Legislation in favour of equality: In India, the Equal Remuneration Act of 1976 prohibits employers from discriminating between workers based on their sex, a good starting point, although compliance by organisations is difficult to monitor.

- Higher levels of transparency amongst employers and between employees:

- Government and government aided institutions in many countries tend to publish pay scales for individual roles but the private sector tends to be notoriously opaque regarding wages.

- In the USA, the Obama administration passed an order prohibiting federal contractors from penalising workers for discussing salaries, thereby giving women a clearer picture of what they were up against.

- Legislation that requires transparency:

- Governments in Britain, Sweden and Germany require employers to share the gender wage gap in their respective organisations annually.

- Iceland went even further: The country ushered in 2018 with legislation requiring all employers with more than 25 employees to obtain an equal pay certificate after submitting to an external auditing process (the certificate needs to be renewed periodically).

- Support from male allies: In 2015, when Hollywood actor Jennifer Lawrence spoke out against the gender pay gap, her co-star Bradley Cooper proposed that in future projects he would share his salary details with female co-stars so that they could negotiate together for better wages.

Given his celebrity status, Cooper’s public support of Lawrence had an important symbolic value.If he and other male actors follow through on his proposal, they could make a significant difference in Hollywood’s gender wage gap, setting an example for other industries. Narrowing the gender wage gap requires cooperation between men and women, and importantly, requires society to view women as equal breadwinners alongside men.

My thanks to Dr Kate Maclean, Senior Lecturer, Birkbeck, University of London, for her comments on this article.

For Further Information See

What Works: Gender Equality by Design by Iris Bohnet. Harvard University Press, 2016.

Women Don’t Ask: The High Cost of Avoiding Negotiation–and Positive Strategies for Change by Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever. Bantam Press, 2007.

Women Don’t Negotiate and Other Similar Nonsense (Ted Talk at TEDxOshkosh) by Andrea Schneider, 2017

Also Read: The Global Gender Gap Report 2017 And India’s Worrying Performance

*The figures only represent an average and different surveys tend to throw up slightly different statistics but all studies indicate that the gender wage gap is significant. There is also variation in the wage gap according to location, industry, sector, age and seniority.

Featured Image Credit: The New York Times

About the author(s)

Jyothsna Latha Belliappa has a PhD in Women’s Studies from The University of York, UK and is interested in issues of gender, work, education and personal life. She divides her time between teaching, writing research and long meandering walks in nature.