When Akshay Kumar waved the ABVP flag to flag off the women’s marathon for tax-free sanitary pads at Delhi University, he was rightfully slammed by many on Twitter. Kumar raising his voice for the cause of menstrual hygiene and against menstrual taboos in Indian society by joining hands with the students’ wing of the party that proudly issues rape threats to women and actively curtails women’s freedom was criticised by many. But one thing that it successfully managed to do was to highlight the insincerity of Padman creators’ ‘feminist’ motivations.

Flagged off Delhi University's Women Marathon. These lovely ladies are taking the cause of women empowerment forward and running for tax-free sanitary pads 🤞🏻 #PadManInDelhi pic.twitter.com/b3v8VKNVmJ

— Akshay Kumar (@akshaykumar) January 22, 2018

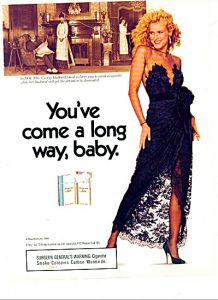

What Goldman had termed ‘commodity feminism’ back in 1992 to describe the tweaking of the message of female empowerment by companies to sell products, most notably through the Virginia Slims cigarettes for women’s ad campaigns, is applicable to a range of product campaigns even today. From Dove’s ‘Real Beauty Campaign’ to ‘Always Like A Girl’ campaign (selling Whisper sanitary pads in India), ideas of women’s empowerment continue to be successfully employed as marketing strategies by brands worldwide.

However, when it comes to ad campaigns, the artifice is staring you in the face because the visible aim is still to sell a product. So, while the woman depicted may be empowered or while the campaign may be advocating men and women sharing domestic workload equally, you still know, through the course of the ad itself that it is a Titan Raga watch or a packet of Ariel detergent that is being sold.

An ad poster for Virginia Slims cigarettes

When ideas of female empowerment are used as marketing techniques for films, the artifice is not revealed because the product – which is the film itself, is marketed as being revolutionary. In a country where films and film stars are highly influential, and in an environment where meaningful mainstream cinema is seen as the means to engage with ‘illiterate masses’, socially relevant films stand on a pedestal, which they seek to elevate through marketing strategies that overstate their scope for social impact.

Also Read: Femvertising: How Corporates Co-opt Feminism To Sell Us Things

Recently, Twinkle Khanna addressed Oxford Union (the debating society of Oxford University in England) where she spoke about Arunachalam Muruganantham, period taboos and poverty. There she said,“PadMan is not just a film, it’s a movement. I hope now women will not be held back or embarrassed by their biology”. On another occasion, Sonam Kapoor distributed sanitary napkins to young school girls as part of a ‘promotional spree’ for her film. Recently, at another event for She’s Ambassador Program in Mumbai, Sonam Kapoor and Twinkle Khanna spoke about the importance of menstrual hygiene.

Actress @sonamakapoor on promotional spree for her upcoming movie #Padman pic.twitter.com/V15mVQ6tvg

— B4U (@THEOFFICIALB4U) January 23, 2018

It is careless to equate a film with a movement for social change. First of all, because it simplifies the problem by positing that people viewing the film is in itself the solution. Secondly, in trying to overemphasise its own importance, it often takes away from other efforts that have been taken in the same direction before, like the 2015 #PadsAgainstSexism movement that was shut down by college authorities in Jamia Milia Islamia.

But Padman is not the only film that has marketed itself as a revolution. The 2016 film Pink too posited itself as a ‘movement’. Citing the same, writer-producer Shoojit Sircar asked the government to declare the film ‘tax-free’ by exempting it from paying entertainment taxes. In the lead-up to the release of the film, Amitabh Bachchan wrote an open letter to his grand-daughters asking them to make their own choices despite what society might have to say.

it simplifies the problem by positing that people viewing the film is in itself the solution.

The letter faced criticism and showed the limits of Bachchan’s alleged feminism, wherein he asked his grandchildren to follow only their paternal grandfathers’ legacy, among other problematic statements. Amitabh Bachchan conveniently became the spokesperson for women making their choices at the time when his film was about to release. In September 2017, when the cast and crew of the film celebrated a year of its completion, many of them shared social media posts that echoed the sentiment of Pink being a revolution that had brought about ‘social change’.

Also Read: A Feminist Reading Of ‘Pink’

A year since "no means no" became a household phrase.

A year since perception of society changed. (1/2) pic.twitter.com/GzL07q6c6P— Rashmi Sharma (@sharmarashmi20) September 16, 2017

Similarly, when Ekta Kapoor’s ALT Entertainment stepped in to distribute Lipstick Under My Burkha last year, the social media marketing campaign for the film was centred around the idea of a ‘lipstick rebellion’. Using the #lipstickrebellion hashtag on social media, the team asked women to share selfies with them showing the finger to patriarchy.

Celebrities and women from different walks of life posed for pictures that they shared with captions telling their own stories. The team also partnered with digital content platforms like Buzzfeed India, Quint and Arre! to create different videos criticising ageism, body shaming, and ideas of the ‘good woman’, among others.

https://twitter.com/sharlene9/status/882526920969027585

I am not saying that such films should not be made. Neither am I denying that they often add to and amplify important conversations, while also diversifying the content of mainstream cinema in India.

However, when we consume these films as feminists, it is important to reflect on their marketing strategies whose aim is to ultimately sell the films themselves. We need to be wary of films proclaiming themselves as social revolutions without laying bare the financial motivations behind those proclamations.

Also Read: My Lipstick Waale Thoughts on ‘Lipstick Under My Burkha’

Featured Image Credit: YouTube, Zee News and The Male Factor

About the author(s)

Shrishti is a student of Media and Cultural Studies. Long rants with female friends help her channelize rage on the world around. Good food, pretentious poetry and cute canines provide her endless pleasure.

I am really impressed the way the content has been brough out. But as a layman reader I am still not able to associate myself with the probem posed here. The movies as such might not be social revolutions in themselves but they certainly have raised the bar of awareness. The article mainly focuses on the ‘issue’ of marketing means adopted by the marketeers that associate societal concerns to promote the movie and in the process couple the money-making and societal aspects.

The only problem here is that we are basing our assertions on our assumption that these movies are solely money-making business which are feeding on social issues for publicity. In contrary to this, what if some of these movies actually go onto impact thinking of the audience and somewhere enhance the way things are looked at by the society, even sub-consiously. In my humble view, one-way traffic is a myth. Entertainment movies (depicting social issues) will always have dual objective of profit and social impact. The marketing strategies will always be a feeder to both these objectives. And it is only fair, for the system needs to exist and sustain.