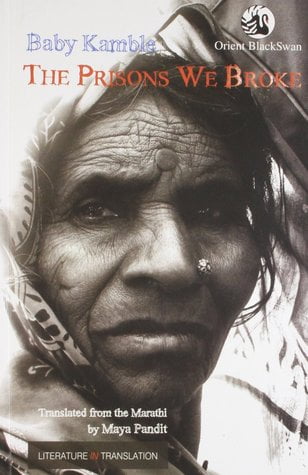

Baby Kamble, affectionately known as Babytai Kamble once older, is best known as a Dalit activist and writer. She penned Jina Amacha (The Prisons We Broke), a vivid narration of her (as well as many other Dalit women’s) lived experiences. The book was translated into several languages. Babytai also wrote several poems and articles delineating Dalit lives and ran an ashram for children from vulnerable communities.

Babytai Kamble passed away on 21 April 2012, at the age of 82. Her words, firmly rooted in Ambedkarite ideology, have continued to inspire Dalit activists to this day, urging them to look beyond the individual to the community in the struggle for freedom and equality.

Early life

Babytai Kamble was born in 1929, to a relatively affluent family. Her maternal grandfather and grand-uncles had worked as butlers for British officers. In her book, Babytai recalls the tale of her birth: her mother had lost three daughters in quick succession and Babytai was given up for dead too when she fell ill and lost consciousness.

A pit was dug for her in the village, but her mother insisted on keeping the ‘dead’ baby in her lap all night until Babytai finally regained consciousness. Those around her sang bhajans and prayed to god that entire night. Her miraculous ‘rebirth’ was attributed to a godman and the powers of faith. Babytai wonders how many children were dug alive in pits due to the lack of medical facilities and faith in godmen.

Her father was a labour contractor who worked on the Mumbadevi Temple in Bombay as well as a milk dairy in Pune owned by the central government. He did very well for himself and was also incredibly generous, sometimes to a fault, spending his money on feeding his labourers until the Britishers paid their wages.

Her book gave us one of the first critiques of twofold patriarchy – by gender and caste.

From him, she learned that one need only earn enough money to feed one’s stomach and not one’s greed and that the true earning was one’s good deeds. However, her mother was never allowed outside the house. Babytai’s grandmother, Sitavahini, had led the revolution against eating dead cattle meat.

Because her father travelled a lot, Babytai and her mother lived with her maternal grandparents, in Veergaon, western Maharashtra. The village (including Babytai’s family) was inhabited by the Mahar community, the same community to which Ambedkar belonged. The entire village was, in her words, “decorated with eternal poverty“. Babytai Kamble treated every household as part of her own family and was on friendly terms with the entire community.

Marriage

The age of marriage for women in the Mahar community was seven to ten years old. Babytai was accordingly married off very young, after which she ran a provisions store with her husband, taking on the duty in the mornings when he went to buy fresh supplies for the store.

This was Babytai’s first brush with literature: as she wrapped the groceries people bought from the store in a newspaper. She slowly started writing her own narration and therefore the community’s. But she was very careful to keep this writing hidden from her husband and most of her relatives for twenty years.

Also Read: 5 Dalit Women Poets Who Remind Us That Caste And Patriarchy Are Not Exclusive

The pathbreaker with a pen

One of the major reasons why Babytai’s writing was path-breaking is because there had been many chronicles of Dalit lives written before her time, but there wasn’t much literature on Dalit women. Her book gave us one of the first critiques of twofold patriarchy – an experience of Dalit women’s lives recognizing their dual oppression: by gender and caste.

Babytai Kamble recounts in detail the reproductive labour of Dalit women. After giving birth, the woman’s stomach would be tied and she would require soft food to line her stomach. But there was no soft grain to be found, despite Mahar women putting out a call in the village for soft food. Women would then often have to swallow the hard jowar for the pain in the stomach.

They would return to their maternal homes to have their first child. Often there would not be enough cloth to stem the flow of blood after childbirth. Many women died in childbirth or after it, so women continued to have children until menopause to ensure at least two to three surviving children.

Babytai also recounts in great detail the influence of Ambedkar. As per casteist and religious diktats, all Dalits had to bow in front of Savarnas as they traveled in the villages. When young married women did not follow this custom, the offended Savarna men would shout at the Mahars loudly in the village square, questioning how the Mahars could possibly deign to get so high and mighty.

The girl’s father-in-law and other male elders would profusely apologize. Then they would come back to their own houses and shout at the girl asking if she wanted the entire community to be let down. Their mothers-in-law and other neighbours would also join in.

When women went into the villages to sell firewood and grass, Brahmin women buying it from them would sit on their shoulder-high sit-outs (the architecture of the houses was designed to maintain caste hierarchy and exclude Dalits) and haggle for the lowest prices. Once this was done, they would shout at the women to carefully inspect the product to ensure no hair or thread belonging to the sellers was left on it, lest it “polluted” the entire Brahmin household. Once this was done, the Brahmin women would throw a few paisa their way as payment, without coming near them.

Once Dalit children started attending school, there were inevitable clashes between them and Savarna children, with several exchanges of harsh words against Ambedkar and Gandhi from either side. Dalit children were segregated in school, while fighting Savarna children at the school tap for water as the Savarnas tried to block their access and teachers placing Dalit children at the back, far away from the blackboard.

Babytai urges her community to remember the lessons from Ambedkarite struggles. She decries those who take to temples and idol worship and encourages remembering Dalit struggles of the past and the way of life before Dr Ambedkar. Her words have immense relevance today as we see the continued prevalence of pernicious caste practices.

References

- The Hindu

- Round Table India

- Out-Caste

- Writing Caste/Writing Gender: Narrating Dalit Women’s Testimonies

- A History of Prejudice

Also Read: Annai Meenambal Sivaraj: The Tamil Dalit Woman Leader | #IndianWomenInHistory

About the author(s)

Mini Saxena is a lawyer from Delhi. When she's not ranting about feminism, you can find her travelling solo, dancing like no one's watching, or reading.