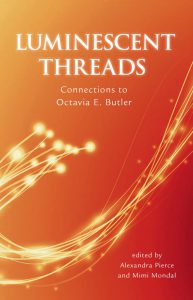

The first Hugo Award nominee from India, Mimi Mondal is a speculative fiction Dalit author. She also received the Poetry with Prakriti Prize in 2010, the Octavia E. Butler Scholarship for the Clarion West Writing Workshop in 2015 and the Immigrant Artist Fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts in 2017.

She currently lives in New York. Her first book, Luminescent Threads: Connections to Octavia E. Butler, edited with Alexandra Pierce, is a finalist for the Hugo Awards 2018 and the Locus Awards 2018.

We had the privilege of talking to her about her work and inspiration.

Pallavi Varma: What were some of the SFF authors you grew up reading – and how did Non-South Asian authors’ writing affect you differently than books written by South Asians?

Mimi Mondal: I grew up reading mostly Bengali literature, of which only Satyajit Ray’s Professor Shonku stories are properly classified as SFF, but also a lot of speculative children’s fiction, tall-tale fiction, horror stories by many other authors like Narayan Gangopadhyay, Premendra Mitra, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Lila Majumdar, even Rabindranath Tagore.

I read the three main books of The Lord of the Rings but not the rest, some stories of Asimov and Lovecraft, some Philip K. Dick, some tattered secondhand DC and Marvel comics but rarely ever entire arcs. In my childhood, I only read Harry Potter, which was entirely contemporary.

In my late teens, I discovered Terry Pratchett, Ursula Le Guin and Neil Gaiman and read everything by them I could get. Then the British Council brought China Mieville to Calcutta in 2010 and I started reading everything by him, but by 2010 I was no longer a child.

The reasons I didn’t read more SFF in English when younger was their lack of discoverability and availability in India, and also the lack of cultural reference. Most of those older white male SFF authors’ works didn’t really “affect” me emotionally as a child.

I wasn’t even a little terrified by Lovecraft, because I couldn’t understand half the things in his stories, but I imbibed (and was kept awake at night by) so much Bengali horror fiction, some of which may have recycled his themes. Much later when I read Octavia Butler, I wondered why I hadn’t read her as a teenager because those novels I would’ve been able to enjoy. But you didn’t find those authors in India when I was young.

PV: Diversity is still treated as a token in most South-Asian mainstream media – an afterthought in a circle of people that wrongly attempts to adopt “colour-blindness” and “caste-blindness” instead of having the difficult conversation about privilege. How do you think we can change that?

MM: Mainstream media is always socially conservative. New ideas and “radical” conversations always start from individual people, then smaller, newer media outlets and by the time the venerable national newspapers from the 19th century pick up those ideas, they have already achieved enough momentum to become somewhat mainstream. This is not only true of South Asia, it’s true of everywhere.

In the West about a century ago, even basic first-wave white feminism was a radical conversation that was only possible to hold in certain small circles, and the people who tried to implement those ideas in wider circles were considered nuisances creating unnecessary trouble. Today in 2018 we cannot even imagine a world without those basic first-wave feminist ideas: women should go to school, have a vote, own property, etc.

Even the occasional unintelligent celebrity who proudly declares she’s not a feminist has systematically benefited from those changes. We cannot convert everyone to our beliefs, even the ones who’ll directly benefit when those beliefs become reality, less so the ones who will lose some systemic privilege they’ve even never had to acknowledge they had.

But if we keep having our conversations, more people will engage, these ideas will slowly become the way things are expected to be, even if by that time most people have forgotten the history of how that happened, and who did it, and how hard the struggle was for them.

Image Credit: Mimi Mondal, Source: Twitter

PV: SFF in India has gained more traction in the past decade. What writing advice do you have for budding Indian authors who write speculative fiction in India and for Indian audiences?

MM: The bar for publishing a novel, either SFF or realism, just to be sold in India is honestly very low – as long as it’s in largely legible English and loosely has a plot, someone will publish it. Hundreds of such novels come out every year, sell about 100 copies if lucky, mostly among the authors’ family and friends, and disappear without a trace.

The famous, bestselling Indian authors, mostly not SFF, don’t write with that goal in their mind. They write for global readerships, Indian included, even if their stories are primarily about life in India.

That bar, obviously, is the exact opposite of low. Reading and engaging with contemporary global literature is a must. There is a high level of craft in considering how a story will work for both the readers of its own culture and readers who have no idea about that culture. How many of us learned about life in Colombia for the first time, or even life in South America at all, from the works of Gabriel García Márquez?

But García Márquez was a bestseller among Colombian readers people first. Similarly, many foreign readers learned about India from the works of Salman Rushdie or Arundhati Roy, but Indian readers read them too. What are these authors doing with their craft to make that possible? They aren’t SFF authors but that particular skill of craft is the same.

There are also highly successful India-specific artistic models, of which the biggest example is Bollywood. Bollywood movies are primarily made for Indian audiences. Some authors take that route too, and Chetan Bhagat and Amish come to mind. But SFF writers from India don’t usually want to consider Amish one of their goals.

But the point is, the audience (any audience) already has a set of tastes. You can’t expect to be read by Amish’s readership if you don’t write like Amish, just like you can’t expect to be read by Rushdie’s readership (largely not the same as Amish’s) if you don’t write like Rushdie.

So, first, you decide who you are writing for – your family and friends, or a global readership, or a popular Indian readership? Then you teach yourself to write like that. The readerships won’t change their tastes according to your convenience. You as a writer have to learn to cater to them.

PV: Navigating identity and cultural spaces is complex. How do you navigate between reclaiming South Asian identity from Western stereotypes while also holding South Asia’s cultural history accountable for the things it did wrong?

MM: I partly answered this in my last question. It’s difficult, not impossible, to add further layers to one’s work, to make it do more things at once. I am still improving my writing. I get many story rejections. Then I try to write a better story – one that is performing all the functions I want it to perform.

Am I always writing with the goal of reclaiming the South Asian identity from Western stereotypes or holding South Asia’s cultural history accountable, etc.? No. While having a harmful social message is undesirable, it’s not mandatory for a fiction writer to be a social messenger of any kind. It’s not mandatory to write a story that can be included in university syllabi.

It’s cool if a writer wants to do that, but demanding those kinds of stories, especially from minority writers, is deeply unfair. White male writers get to write the fun stuff, and we have to write the heart-wrenching, identity-reclaiming, history-revising narratives to be taken seriously? How’s that for breaking stereotypes?

We fiction writers aren’t helping any cause if our stories are so tiresome that even people who agree with us can’t bear to read them. Stories only achieve those important-sounding things when they succeed as stories. You need to let them breathe as stories first.

Before we start engaging with other people’s stereotyping, we need to be sure that we don’t end up stereotyping ourselves, especially in response to other people’s stereotyping. Don’t let the monsters turn you into a monster, as the great Nietzsche had (possibly?) warned. Are you writing the stories that feel true to you? Are you putting massive amounts of excitement and faith in them which will, in turn, infect the reader, and not defensiveness and lecturing?

We women and minorities (and more so minority women) often have a tendency to over-explain ourselves, because we’re always trying to persuade more “legitimate” people that we are good enough too. That is a weakness, especially if it permeates your craft.

True freedom and control of your craft is when you can put whatever you want in your story, make it as weird and complex as you like, and still keep the reader engaged. That’s what I strive to do, and occasionally when I succeed, all those other things kind of fall into place all by themselves.

PV: What has your experience been with carving a spot as a Dalit WOC in a field that’s predominantly represented by white cis-men?

MM: I may be the only Dalit WOC currently publishing SFF internationally, but it has largely been a very accepting, conducive space for me. The difference between conservatives and liberals – on a large, extremely simplified level – is that conservatives approve of only one kind of people, usually exactly like themselves, while liberals approve of every kind of people, including those who are not entirely like them.

Being part of the liberal, diverse side of SFF means that in the past few years I have met and had to educate myself on the complexities of many kinds of people who are nothing like me, including people of different non-white ethnicities, people from countries I have never visited and known nothing about, trans people, disabled people and others.

It takes a lot more work and consideration than being conservative, which is easy. The good thing is that people in the diverse side of SFF do that extra work, and I’m receiving the benefit of it as well, because why else would anyone care that I am Dalit?

That is the simplest answer. I do end up feeling lonely and misunderstood often. I get tired of answering “Dalit questions,” which is not what I signed up for. I get jealous when my white peers, even those who are my friends and don’t specifically want that privilege, are treated and acknowledged better than I do.

Sometimes I am completely exasperated and heartbroken when other minority writers, those whom I expect to be my nearest allies in the community, end up turning cutthroat competitive for the very few resources that are available to us. Being a minority seems to have only two options: you’re either the Model Minority – relentlessly pleasant and not upsetting anyone, or you’re completely nasty, aggressive or irresponsible.

You’re not allowed the space to make mistakes and grow from them. Say a not-thoroughly-considered sentence or crack a thoughtless joke at the end of a tiring day, and that will be quoted to eternity and used against your credibility. People just are naturally disposed to believe that you’re bad, inauthentic and not really cut out for this.

But this is not a problem specific to SFF, and it’s not perpetrated solely by white men. When you’re at the bottom of the ladder, often the person immediately holding you down isn’t the one at the very top but the one on the rung just above you; the one at the very top doesn’t even know you exist.

While I keep talking about white supremacy in SFF, and it is important to talk about it, I’ve never met or been attacked by any of those white men. What I say matters nothing to them. But what I say will be closely read by my peers, and a section of readers who will take every word I say as the Official Statement of the Dalit Community. I didn’t sign up for any of that. I wonder how it feels to live without that pressure sometimes. I have never known it.

Image Credit: Mimi Mondal, Source: Twitter

PV: What is your writing process like? Do you plan everything, research, and then write? Or do you wing it, going along with whatever idea strikes when you find some new information?

MM: I spent eleven years of my life at universities and accumulated three Masters’ degrees, so I did do a lot of research in the subjects that interest me. One of the things I learned in the process is that my expression is more suited to creative writing than academic writing. Whenever I research a subject, I come up with fiction situations within it rather than academic-paper ideas.

So the stories I write now are largely tips of years-of-academic-research icebergs, even if that particular story idea came up spontaneously. I still read a lot of news on different verticals, nonfiction, research, trivia like Wikipedia articles, and so on. I read them because I enjoy them, so I don’t think of that as specifically doing research for stories, but sometimes they turn into story inspirations.

After I finish writing a mostly complete draft, I send it out to some trusted friends, often other writers, for comments. I try to get at least a South Asian friend and a non-South Asian friend to read each story so that I can get a sense of whether the story has achieved that global-readership balance I was talking about earlier.

I listen to their feedback and revise the story a few times. Often a story needs to be revised even after being accepted by a magazine or anthology because the editor wants some adjustment. Some of my story ideas are spontaneous, but the stories themselves take weeks, often months, to be finished.

I feel it’s important to admit this because we need to break down the myth of talent as a miracle or inheritance and learn to acknowledge the value of training and hard work. These are the larger cultural thought patterns through which class and/or caste hierarchies are maintained.

We also need to break down the myth of writing as a solo artist, as opposed to something like filmmaking which is collaborative. You always need to consider the readership and its expectations, or why are you even trying to publish? Execution is always more important than inspiration or the idea itself. Flawless execution doesn’t happen in a flash.

PV: A lot of mainstream media produced in India has always relied on emotional authenticity over technical/plot authenticity. How do you think that impacts creators who want to write SFF, a genre that often involves complex worldbuilding that follows rules?

MM: Let me give you the example of a Bollywood movie again; I’m pretty sure that’s what you were going for in the question. When a heroine in a Bollywood movie breaks into a song-and-dance routine, a number of background dancers in matching attire miraculously show up. Your audience will be thrown off if those background dancers are still there after the song is over and it turns out that they’re her friends. That’s just not something the conventions of that genre allows.

Every genre has these bare bones or building blocks, whatever you call it – these underlying structures that identify the work as belonging to that genre and guide the audience’s expectations towards it. They work unconsciously in their minds and contribute to the phenomenon known as suspension of disbelief.

These are largely cognitive tools, rather than limitations. Not every work in a genre has the same story. Innovative things can be done while maintaining the genre’s rules, and the rules are not a checklist but more of a general direction. Some of them can be bent, subverted, ignored, broken, but if there aren’t enough of the framework remaining to at least identify the work as belonging to that genre, then the audience’s suspension of disbelief collapses.

As a creator, one always has to be aware of these underlying structures, and the sign of a good creator is how well you conceal your building blocks so that the entire work feels like magic. Are you kidding me that a Bollywood movie or a K-serial takes less complex calculation than an SFF novel?

If a certain work in those genres seems unintelligent or irrational, that’s also a conscious decision by its creators – they’re not aiming for high intellectual accomplishment, they’re aiming for what the majority of their audience will pay to watch, and achieving it. On the other hand, if a work feels so spontaneous and emotionally authentic that you can’t believe it was put together with calculation, that means its creators did an extremely good job. Any highest-level SFF novel (or any other work of art) would do the same. If it doesn’t, it’s not yet of the highest level. Genre conventions have nothing to do with it.

PV: You work both as an editor and as a writer. How do you think one job has affected the other?

MM: I think being an editor makes me a slower writer. I pointed out right now how it’s important, as a creator, to recognize and be in control of the underlying structures of your work. But an editor’s gaze goes far deeper than that, and sometimes it overwhelms the spontaneity I need to write.

For every sentence I write, my editorial brain is also at work, so I can’t move on to the next sentence until this one is the absolute best I could do. It’s impossible to switch off the editor completely, but I have to try or I’d never finish writing anything.

On the flip side, being a writer helps me understand as an editor why a writer I’m editing is making certain structural mistakes because I’ve probably made most of them as well. It makes me sensitive to what kind of suggestions helps a writer evolve and not give up on their work. I can tell them exactly what I did as a writer to overcome a certain hurdle. Overall, I think it makes me a more efficient editor than I would be if I wasn’t a writer.

PV: You’ve written about how the world of academia in India can be an elite circle, often looking down on students from Dalit backgrounds. In what ways do these power hierarchies manifest among South Asians abroad?

MM: I went to university in both these countries but not in South-Asian-specific disciplines, and have never had a primarily South Asian circle of friends or colleagues abroad. Besides, the first time I went abroad I had already been an editor at Penguin India and was funded by a Commonwealth Scholarship, so I was not only Savarna-passing but also elite-passing. My family is neither, but nobody was meeting my family.

I was no longer dependent on Indian or Savarna-based power structures to either protect or confine me. I would obviously not be receiving the same discriminations that a Dalit student with clear markers in a largely Savarna student community.

Still, I received my share of microaggressions, because when you’re a student abroad, you can’t avoid at least some connection with the Indian students’ community at your university. You may politely skip the all-veg Diwali party or free-groping Holi dhamaka, but you’re subject to the same visa laws and international-student restrictions, which are constantly changing and never very benevolent.

While I was in India, especially in college and after, I socialized only within a small community of educated, liberal, humanities-background people – all Savarna, but possibly the least casteist part of it you can get, and also people who understood my work and qualifications. At a foreign university, you get Savarnas from a much larger cross-section of India.

Not all subjects at a university are equally competitive. You may be the scholarship student at the most prestigious department of the university and another Indian may be paying their way through a certificate course or an easy Bachelor’s degree and you’re both part of the international students’ community and subject to the same laws. This may be the kind of person you wouldn’t even have met back home. Immediately you’re reduced to the caste and the assumptions that your mere name signifies.

This is what I want to tell the people who argue that I’m a “privileged Dalit”. As long as caste hierarchies exist in any form, no Dalit is more privileged than a Savarna. Even with my complete lack of dependence on Indian communities, I suffer from the discrimination.

At the University of Stirling, where I was the Commonwealth Scholar, a Savarna guy who was doing one of those easy courses at his family’s expense took me aside at an international students’ event and propositioned me for sex. He did not do that to any of the Savarna women in the room, only me.

I laughed at his nerve. That guy didn’t speak correct English, dressed in poor taste, didn’t read or watch cool nerdy stuff, so in external cultural sophistication terms, he was nowhere near the same level as me. This is also a paradigm of privilege that exists, I agree.

But a few days later, I realized that he had spread the rumour in the Indian students’ community that he did have sex with me, and to my horror, most other Savarna students who socially knew both of us believed him.

This caused me no permanent damage because that wasn’t my primary circle of friends, but what if I was a less culturally privileged Dalit girl whose only support system abroad was that Indian students’ community? What if I wasn’t the kind of progressive who laughed away rumours of sex? What if somebody told my parents?

Besides, if cultural sophistication privilege really cancels out caste discrimination, why did all those other Savarnas so easily believe I had sex with that guy? Everyone understands that “girls like me” don’t even date, leave alone have sex with, “guys like him”. But that paradigm only fully applies when both the guy and the girl are Savarna.

Everyone in India, especially from more casteist backgrounds, also understands that Savarna men don’t often date or especially marry Dalit women, so for a Dalit woman to be worth consideration for a Savarna man she has to be compensating in other ways. According to the majority of that Indian students’ community, I was not only completely on that guy’s level, I was in fact beneath him.

He was wealthy, I was a scholarship student. Dalits being scholarship students is a common understanding in India, though the Commonwealth Scholarship has zero to do with caste. Sure, I could speak a little more fluent English and “books-wooks padh leti hai“, but did that mean I was out of his league or something?

I do have some Savarna friends in the US, mostly from SFF and social-justice circles, but when they go to a Durga Pujo or Diwali, I politely say I have work, though I miss those festivals too. While these Indian festivals and Bollywood movie outings are a slice of home and comfort for other Indians, for me they’re a constant risk of at least insult, if not substantial injury.

As Indian communities abroad are so small and an overall minority, they’re also more tightly knit. The casteist, the sexual predator, the Trump voter, the wife beater, the one who doesn’t read, the one who spits paan juice on the sidewalk – everyone gets invited to the same “Indian cultural events” with the rest of liberals in a way it doesn’t happen back in India.

There’s strong policing against exposing anyone in the community for offences, in case it makes all Indians “look bad to the white people”. Oppressive structures from the homeland get calcified and carried down generations in Indian communities abroad, all in the name of preserving tradition and/or respectability in the eyes of white people.

Image Credit: Twelfth Planet Press

PV: Congratulations on your nomination for the Hugo! How does it feel to be nominated for such a prestigious award?

MM: Thank you very much! Honestly, the most overwhelming change has been in the number of people from India interested in talking to me. I’ve received prestigious scholarships in the past, but those have mostly been private accomplishments. I’ve worked with some famous writers, but I was one of the “industry people” invisible to the public.

All this sudden attention feels a bit like playing a character in a video game, who’s probably a slightly enhanced projection of yourself, but she’s out there in a virtual world going on adventures, while you are sitting in your bed in your pajamas, controller in hand, as you eat Maggi from a plastic bowl.

Becoming part of a glorious historic tradition is such an abstract thing that it’s hard to “feel” in concrete terms. Here in New York I still know the same people and they treat me exactly the same way, and some of them are Hugo nominees and winners as well. There’s no elite Hugo Nominees’ Club where I can now hang out.

Maybe something will finally sink in when I go for the Locus Awards weekend in June and the Hugo Awards ceremony in August. Or maybe they will feel like just other conventions I have attended in the past, who knows?

I’m doing my work as usual because, in the short term, I still have to make next month’s rent and in the long term, I won’t have any other stories to show if I don’t write them. So, I don’t know… it feels unbelievable because immense, but also another kind of unbelievable because not much really has changed in my life.

Also Read: 9 Indian Women Authors To Look Forward To In 2018

Featured Image Credit: Malinda Ray Allen

About the author(s)

Pallavi Varma grew up in Bangalore but spent a lot of her time living in the fantasy worlds she creates for her stories. She has a BA in English Honours from Christ University, an MA in Creative Writing from Cardiff University, along with being a professional binge-reader, kpop-enthusiast and Netflix-watcher.