Mainstream history has neglected women and excluded them as silent voices of history. One of the main reasons for this has been its privileging of public world of men. As writer Aparna Basu notes, “Traditional history has tended to focus on areas of human activity in which men were dominant – politics, wars, diplomacy – areas in which women had little or no role.”

The devaluing of history of women also takes place through situating topics related to ‘position of women’ in between other themes of ‘food or clothing’ or ‘varna’ in history textbooks. Through this we get to know about an abstract category of ‘women’ and we fail to sense their actual presence or know about their real experiences.

Against this backdrop where women have been erased, trivialised, how have women been retrieved from history and why is this exercise still so important?

Mainstream history has neglected women and excluded them as silent voices of history.

Having a strong sense of history and identity is especially important for women. The past is not an obscure, distant reality for most us. We live with the present sense and effects of history. Women, especially due to the work of nationalist historians, have been turned into markers and carriers of Indian civilization. With the partition of India, we saw women were turned into hollow symbols of a nation and a religion. During the violence of Partition, violating a woman’s body was symbolic of humiliating her entire community and these ideas continue to persist in our own times.

Feminist history not only breaks such stifling ideas but creates spaces to bring in the voices of women to create a more authentic reality of their lives. Annie Zadie notes in her book Unbound: 2000 years of Indian women’s writing, “Women bring to their writing the truth of their bodies, and an enquiry into the different ways in which gender inequity shapes human experience (and destroys lives).“

Personal, intimate details of women’s lives take centre stage when women write history. Charu Gupta, a feminist historian, shows how while men focus on the big picture and the larger politics, women bring into account intricacies of small events, of routine work in homes and household relationships. They move beyond the cataclysmic to bring in the reality of their lives.

Feminist history not only breaks such stifling ideas but creates spaces to bring in the voices of women to create a more authentic reality of their lives.

This is not to say that women didn’t write political works or that there was a sharp divide between their personal longing and the political circumstances of their times. The work of women like Savitribai Phule or Pandita Ramabai is indeed political writings, the importance of which is not lost today.

The absence of women from history is not always incidental or a result of a mere mistake, it is because of suppression of voices of women. This was the case for Pandita Ramabai who was written out of history. Someone like Annie Besant who believed in revival of Hinduism and warned Indians against adopting Western values to preserve the true essence of Hinduism was accommodated within mainstream history. However, Ramabai with her scathing opposition to Brahmanical patriarchy and her conversion to Christianity as a form of protest, was not seen as worthy enough to be remembered. Her story has now been retrieved through the efforts of feminists in works like Rewriting History: The Life and Times of Pandita Ramabai by Uma Chakravrti.

Feminist history writing has had important consequences for the women’s movement as a whole as well. History writing and women’s activism are hence interrelated which sustain and feed each other. The understanding of patriarchy, women’s agency is based on historical analysis of gender. The development of strategies and vision with respect to how women have historically come to occupy their current position is an important advantage.

The grassroots women’s movement which brought to fore questions of violence, dowry, rape, reproduction, and women’s health, on the other hand pushed the need to theorize experiences of women in universities and colleges.

Feminist history writing has had important consequences for the women’s movement as a whole as well.

The feminist intervention entailed not only recovering women in history but challenging and changing the discipline and its methodology. By critically engaging with traditional sources and using oral histories, biographies and autobiographies, women’s history has been recovered.

Feminist writing of history has made an important political claim that our reality is gendered. Thus, feminist history writings are political acts in themselves which have been written in reaction to contemporary political events. Urvashi Butalia in response to the violence of 1984 riots decided to write the history of women during Partition of India in her book The Other Side of Silence. Her aim was to show that the Partition is not a remote event restricted to history textbooks but a haunting episode which continues to linger in our politics and lives.

Apart from the wide ranging merits feminist history has for the women’s movement at large, it also carries appeal for individual women. It is a way of finding historical identity and receiving assurance that women too have made history. FII’s project ‘Indian Women In History’, where more than 300 women have been profiled, is geared towards uncovering lives of women who are missing from the history we read in our books.

Also read: 5 Indian Women Historians You Need To Know About

Talking about the lives of individual women and their contributions is a way to compensate for the absence of women in history. The history of ‘women worthies’, with its aim to bring forth forgotten women and their legacies, carries the sentiment of ‘we too’. This is not a simple exercise in merely naming women who did great things but to study how they exercised agency and power under specific historical circumstances.

However, this special emphasis on individual defiant and exceptional women leaves out the history of the ordinary mass of people. Moreover, women don’t form a homogeneous category and because of this it is unjust to focus solely on ‘women’s history’. This assumes that all women had similar experiences during a period and we can classify and account for these experiences simply under the banner of ‘women’s history’. It is important to confront, and engage with our differences and not sideline them in our quest for a collective sense of the past.

For example, the history of Dalit women’s participation in the Self-Respect movement led by Periyar is an important instance of the unique fights which Dalit women waged. Veerammal was a Dalit woman who questioned Periyar’s strategies within the movement and consequently split away from it. The clubbing together of all women’s voices leaves out such histories.

Feminist history has been able to counter the ‘objectivity’ in mainstream history writing by showing that history from the point of view carries special importance. This makes it noteworthy that women are writing about their own history because of their need for an identity and sense of self. The urge to write feminist histories comes out of the lives we’ve lived. We’ve been told that our stories don’t matter or are insignificant in nature. We’ve been cast off as people without history thus denying us any kind of meaningful relationship to the past or to ourselves. Feminist history is thus a fight against the easy manipulation of history to discount the humanity and presence of an entire people.

References

- Lerner, Gerda,‘Placing Women in History: Definitions and Challenges’, Feminist Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1/2 (Autumn, 1975), pp. 5-14

- Chakravarty, Uma and Roy, Kumkum, ‘In Search of Our Past: A Review of the Limitations and Possibilities of the Historiography of Women in Early India’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 23, No. 18 (Apr. 30, 1988)

- Rewriting History: The Life and Times of Pandita Ramabai by Uma Chakravrti.

Also read: Queer History: How Did Queer Women Network Before The Age Of Internet?

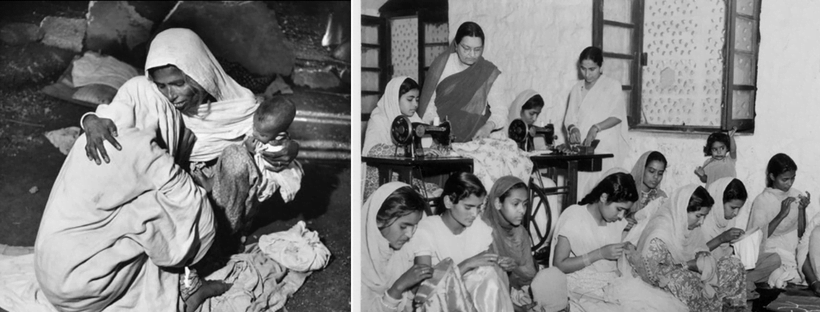

Featured Image Source: LSR History and The National Archives

About the author(s)

Umara is pursuing her bachelors in history from St.Stephen’s college. Feminism to her is an evolving process, she doesn’t feel the need to define her version of it, because she comes from the belief of autonomy of the oppressed classes.