Sumeet Samos. You might have heard his name before. He has been making groundbreaking work in terms of de-Brahmanising the Indian hip-hop scene. In the world of Indian hip hop, we mostly see upper caste, upper class men talking about money or objectifying girls. Very rarely do we hear them challenge social hierarchy or caste injustices. Hip-hop and rap are understood to have originated in the wake of the Civil Rights movement in America and served as vital instruments of resistance to classism, racism, and oppression. They have always been historically and currently used as a medium of resistance – a vital component of the genre that is absent in the Indian scene.

Also Read: In Conversation With The Casteless Collective: Dismantling Social Injustice Through Music

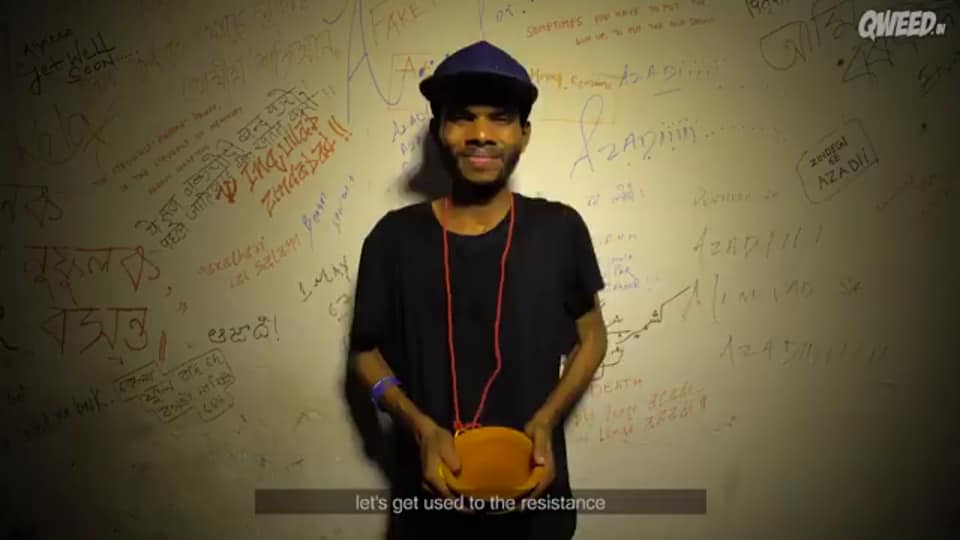

Sumeet Samos, a postgraduate student in Spanish language from JNU and an anti-caste student-activist from Tentulipadar – a village in southern Odisha, serves as the perfect candidate to introduce Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi narratives in Brahmanical Indian hip-hop. His most recent project, a collaboration with Qweed Media, aims at bringing out an anti-caste narrative in the form of a hip-hop single in Hindi that he has composed and performed.

In analysing Sumeet Samos’ use of language and metaphors in his lyrics, it becomes clear that he is a rapper whose politics and music are not meant for the Savarna (upper caste) gaze, nor are they sugarcoated to make them more palatable. His latest single Ladai Seekh Le (Learn To Resist) will especially resonate with those who have ever been subjected to Savarna oppression – it is a call for a revolution; one that was envisioned by revolutionary Bahujan political torchbearers like Ambedkar and Phule.

Read on to know more about this trailblazing rapper who’s challenging the fabrics of society as we know it.

Ruth: The concept of your new music video Ladai Seekh Le is very aesthetically powerful. Where was it filmed and how did you come up with the concept?

Sumeet: The music video was mostly shot in bastis (slums) in Delhi where Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi migrants inhabit. We did this to link it to my own growing up in similar surroundings and how I saw caste from that location. I conceptualised this track over a period of 3 to 4 months and with my verses, I also wanted to specify what exactly I was visualising. All the verses in the track have already been part of the anti-caste discourse, I just attempted to put these huge critiques into a few lines.

Ruth: Who or what has been your biggest inspiration in terms of your activism and music?

Sumeet: In terms of activism I am greatly inspired by Savitri Bai Phule, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, Malcom X, and also the many autonomous Dalit women organisations. In terms of hip-hop, I am inspired by Joyner Lucas, Childish Gambino, Kendrick Lamar, and Tupac.

Ruth: How do you feel about non-Dalit rappers like Raja Kumari talking about Dalit experiences in their lyrics and how do you feel about artists in general (slam poets and rappers for example) speaking on Dalit experiences?

Sumeet: It is atrocious to hear upper caste rappers like Raja Kumari who appropriate the life of slum-dwellers for their music without ever having lived in it. All she has is her caste capital and networks, and through that she tries to speak for and speak over hip-hop artists who are gradually coming up from the slums. This has historically been the case with most upper caste performers – wherever there is a growing influence, popularity, and power, they will revolve their verses around that. Her verses like “untouchables with Brahmin flow”, “we do it for the slummies with the barefeet”, “thousand Gandhis”, etc., in the recent hip-hop track Roots is extremely casteist and patronising. She reinforces the dominant caste notions and the upper caste version of history. She has no right to speak about what politics we choose and Gandhi has no place in our lives.

In general I think the slam poetry scene in India is nothing but an elite upper-caste social ghetto where rich upper caste kids with command over English and Hindi are allowed to go and speak. This is not transformative at all and it doesn’t reflect the living realities of the majority of this country the Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi masses. For the Indian hip-hop scene it will take a long time to get to the point that black hip-hop has reached – to be instrumental in voicing out the concerns and politics of the most marginalised section. As long as political Dalits, Bahujans and Adivasis are not at the centre of this space spitting their verses, it is just status quo.

Ruth: Do you think it’s important for music to be political?

Sumeet: Yes, more so for the marginalised communities because it becomes a powerful medium to spread emancipatory discourse and also to counter the hegemonic discourse of upper castes in this country. The upper caste propagate their politics through music where they make sure to sustain their status quo by enslaving the consciousness of the oppressed sections, so it becomes very important we use the same medium to articulate our politics. One or two among them are speaking about slums – poverty doesn’t make much difference to our lives.

Ruth: In the lyrics of Ladai Seekh Le (and your other singles too) there’s a lot of anger and calls to resistance. What are the ways DBA (Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi) musicians can counter and resist Brahmanism in the music industry?

Sumeet: The anger is a product of almost two decades of my lived experience coupled with my reading of anti-caste literature and involvement in activism. I think we as DBA musicians who consciously want to use music as a medium on a big scale, should gradually build our own autonomous institutions, something similar to what Casteless Collective is. This way we are taking control over our own music and production. Most importantly, we need to support each other in terms of network and resources.

Ruth: The music video features a lot of symbolism like the smashing of the clay pot, reading of Gramsci, and the shots of various kids while you were naming Dalits who have been institutionally murdered. Can you explain to our readers what these mean?

Sumeet: The clay pot hanging on my neck is a reference to the caste supremacy of Peshwas in the 19th century and what it meant for Shudras and untouchables back then. In the video, I am in a modern outlook, but the clay pot as a burden continues to hang on my neck. This shows the trajectory of how caste has been a constant for centuries – only with varying forms. Smashing the pot signifies breaking caste.

A still from ‘Ladai Seekhle’. Image Source : Youtube

In his prison notebooks, Gramsci talks about organic intellectualism which is about intellectuals of the oppressed community where lived experience and ground reality is combined with a structural analysis. So this is a reference to the importance of DBA intellectuals as opposed to the upper caste knowledge producers who have no relationship with labour and lived experiences.

I refer to the names of the Dalit students who were forced to commit suicide due to institutional caste harassment and also names of Dalit men who were murdered to death by the upper castes for loving upper caste women. There is a visual where a young Dalit boy is standing in front of Ambedkar statue and that particular statue is locked from outside. This is to show the caste hatred that the upper castes harbour for Dalits, that even a statue of Babasaheb Ambedkar who represents dignity and self respect for us has to be locked and protected from their vandalism.

Ruth: Hip-hop and rap are historically genres of resistance and rebellion. The same can’t be seen in the Indian rap scene and a lot of urban dwelling upper caste people in India revere black rappers from the west and talk about western intersectionality (for ‘wokeness points’ maybe) while ignoring DBA artists. Do you think this is an example of how deep upper caste hegemony is in India? What are your views regarding this?

Sumeet: Yes, very true. Hip-hop and rap have historically been mediums of resistance and articulation of oppressed politics. Like I said, upper castes as a collective identity do not possess any morality – they revolve around influence, popularity and power; and accordingly they act. There was a time when crossing seven seas was a taboo for them but they broke it when better opportunities came their way from the colonisers.

It is hilarious to see the upper caste oppressors from here comparing themselves with the resistance of the oppressed black community while keeping out DBA artists – the ones whom they and their kith and kins stigmatise and exclude from the very spaces of music which is built by the expropriation of Dalit-Bahujan labour. They don’t want to hear the truth from us and neither will they speak because it hurts their hegemony. Now, we are gradually starting this process of a counterculture in the music scene and this will surely create ripples.

Ruth: What advice would you give to up and coming DBA rappers who might not have the resources or support to market their music?

Sumeet: If we don’t have resources and support, It’s better to start with putting up our work on social media and this will surely gain attention from DBA platforms. I started similarly and in fact, this is my first properly recorded and shot video after almost a year and half of putting my work on social media. I very sure this helps in networking and connecting with DBA communities.

Also Read: Music As A Tool For Inclusion: Aikya Brings Together TM Krishna and Jogappas

FII thanks Sumeet for taking out time from his busy schedule to answer our questions. Follow his updates on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.

All images courtesy of Sumeet Samos.

About the author(s)

Ruth is angsty and tired. She is also the co-founder of Nazariya LGBT and a former Digital Editor at FII