Write a Facebook post in criticism of the ruling party, and your account disappears.

Grow food for a living? One sudden day, your land and home could be (is being) taken away because, of course, sabka saath-sabka vikaas.

Fake video of a Muslim male groping a Hindu female goes viral, and a mob is ready to cause blood and fire. For, Hindu-ness is Indian-ness. And desh sewa is param sewa (The best service is one, for the country).

Dangerous times we live in!

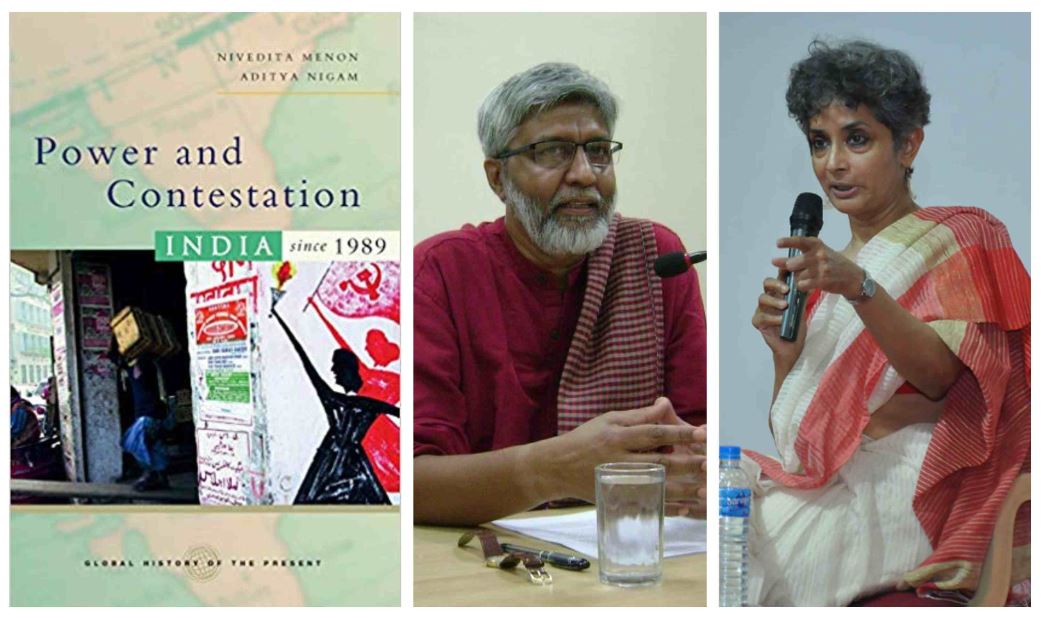

But is this a recent phenomenon? The book Power and Contestation by Nivedita Menon and Aditya Nigam written in 2007, suggests otherwise. It traces India’s complex internal histories and external power relations since 1989 that have shaped the notions of nationalism, development, oppression, and violence as they exist in the contemporary times.

Image Source: Governance Now

5 Dominant Notions That The Book Challenges:

India-ness is Hindu-ness

“Are non-Hindus Indian? Yes, but only if they agree to be ‘Indianized’ and recall that their forefathers were Hindus”.

The attempt to ‘Indianise’ the non-Hindu population has been traced in the book in how Hindutva stepped up its ‘reconversion‘ drive in 1990s to assimilate Muslims, Christians, and Tribals (Adivasis). People still left untouched were (and are continued to be) asked to adopt the ‘Hindu’ ways of life – be it clothes, mannerism or culture at large. For instance, all the beefed up controversy around what to eat and what not, so that they mandatorily succumb to Hindutva politics.

Also Read: Narmada’s Story of ‘Development’ And Destruction

The book also repeatedly mentions how dissent towards Hindutva and anything that the ruling parties order is dealt with. It seems that not much has changed even ten years after the inception of the book. Resistance from varied sections of society – women, tribals, farmers, rural inhabitants and queer people have been continuously met with severe brutality at the hands of political players. It is interesting however to note this:

“All struggles, from the late nineteenth century to 1947, that survive in memory today, are accommodated into the history of anti-imperialist struggle, tucked cosily away into a pleat of Mother India’s sari. With the coming of Independence, however, any such assertion is instantly transformed into an anti-national act.”

Leaders are determined to ’empower’

“Hum wade nahi, iraade le kar aye hain”

(We have come with intentions, not promises).

“Beti bachao, beti padhao”

(Save girls. Educate girls).

Celebrities, political leaders, and NGOs have gloriously used such electoral campaign slogans today and earlier for their claim to fame. If anything, these big shots work unceasingly to strengthen the already existing power based hierarchies. The ‘leaders are determined to empower’ rhetoric is a feeble claim well exposed in multiple chapters of the book.

AFTER Independence, however, any such assertion that resembles the freedom struggle is instantly transformed into an anti-national act.’

The book begins with a chapter on the political expression of caste. The authors point out how caste and reservations have been used by all political parties for their own electoral benefits in the name of empowerment. They demonstrate, for instance, how in the late 90s and later in 2002 unlikely allies were created between political formations representing the Brahmins (the most privileged and dominant caste group) and the Dalits (the most oppressed caste group).

This is a dilemma that has puzzled many observers of Indian coalition politics in the recent past. The authors also comment on how the banner of reservations has become a potent symbolic weapon of electoral mobilisation used by most mainstream politics.

Image source: Hindustan Times

The second chapter comments on how the Hindutva ideology through ages has masked their ‘use’ of women by placing them at the pedestal of ‘nurturing mother’ and the ‘fearsome destroyer of evil’. The book states that, “Both in Ayodhya movement, and in Gujarat violence, women are present everywhere, articulate and active. A television image during the latter event, illustrated Hindu women laugh and chat together in the winter sun on a rooftop, smiling shyly at television cameras as they make missiles and firebombs with homely materials: old saris, stones, kerosene oil from their kitchens. Much as they might get together to make pickles and papads at other times”

The book criticises the general notion of ’empowerment of women’ which has increasingly become a tool for the rich upper class women to establish NGOs and generate funding to ‘rescue’ oppressed women. The funding is mostly provided either by the government itself, or its allies, which clearly means that while reforms (in the interest of the government) are funded, the revolution is not!

3. Unity in diversity

“Anekta mein Ekta“ (Unity in Diversity) takes pride in the irony that we are a diverse country, but live in an overarching single national identity. The book intelligibly highlights this irony as not “the natural order of things” but as a carefully crafted strategy of the dominant caste and class.

The attempt to unify is but an attempt to establish one single dominant ideology – that of elite Brahmanical Hinduism. It also then helps to cleanse out people who do not ‘belong’. In the chapter ‘When was the Nation?’, the instance of Nellie Massacre has been quoted apart from many other tragedies, where Bengal Muslims were killed on account of being ‘foreigners’. According to the book, “They did not (and till date don’t) recognize that the movement across North East (wherein 98% of the borders are international) is dictated by ethnic affinities that cut across borders dictated by traditional forms of livelihood and ecological factors”.

the Hindutva ideology through ages has masked their ‘use’ of women by placing them at the pedestal of ‘nurturing mother’ and the ‘fearsome destroyer of evil’.

The other part of the same chapter chronicles the insurgency in Kashmir, starting right from the question of accession to India in 1947.

It elucidates the complexity of religious composition of J&K. The region of J&K comprises of 95% Muslims in Kashmir Valley, 50% Buddhists in Ladakh, and 66% Hindus in Jammu. Throughout the various phases of militancy and political feuds, the state has nowhere been close to achieving ‘unity’ in its diversity. And, why should it? It is prevalent that all majority sections of the population in the state have been vying for establishing dominance of their own religious identities. This has nevertheless taken violent forms within the territory and across the border.

Also Read: Not In My Name – Delhi Protests The Lynching Of Minorities

These instances clearly illustrate the perpetual anxiety generated by the need to preserve the nation that is always under the threat of disintegration.

Vikaas Sabke Liye (Development is for everyone)

Image source: The New Leam

The book brazenly critiques the idea of development as it claims that the 90s did not just bring the ‘cassette revolution’ or cable TV channels in every home, but much more that haunts us in the present age.

The book reveals that, “In June 2004, armed police and bulldozers arrived in the town of Harsud, Madhya Pradesh to forcibly evict the residents from their homes. The 700-year old town was now reduced to rubble.” All damned for dam!

The book also claims “Jadugoda, in eastern Indian state of Jharkand in 2011 recorded extensive radiation pollution due to uranium mines and nuclear energy plants. The population comprises of very poor tribal people whose exploitation and neglect is of little interest to the grand narrative of national development”.

A native of Jadugoda, Laxmi Das has had three miscarriages and lost five children within a week of their births. When her ninth child, Gudia survived, she considered herself fortunate until she discovered that her baby has cerebral palsy and would be bedridden for life. Gudia passed away in 2012, leaving the scars of her memory. In Jadugoda, a uranium-rich district, there are many women who share Laxmi’s fate. This is however, not the only way the future of these people is dumped. Several other impacts of these energy plants include contamination of ponds, high level of radiation on roads on which the trucks carry uranium, and also contaminated vegetation and soil. The dumped nuclear waste can remain radioactive and dangerous for millions of years.

The dumped nuclear waste can remain radioactive and dangerous for the local residents near the energy plants for millions of years.

The above are only two snippets of the various instances from the book that describe how development is not for everyone but for the dominant class, caste, and religion as is evident from who benefits from it and who protests for their rights.

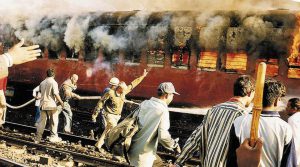

‘Left’ is right

In the chapter ‘Old Left, New Left’, the authors dismantle the popular notion that Indian politics is about a binary – left and right that stand opposed to each other. It demonstrates how it was not just the high muck of industries or the corrupt right wing leaders who embraced policies that brought infinite wealth and power for a few. They track the journey of Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPM), specifically accounting the Nandigram revolt where the CPM-ruled West Bengal suppressed protests and how the party consolidated with land reform programmes.

Image source: Outlook India

They mention that, “The end of 2007 saw the CPI(M) facing a massive opposition to its acquisition of land for an industrial project for the Tata industrial house in Singur’. They had become indistinguishable from other parties committed to the neoliberal agenda.” On multiple occasions, the left have reaped benefits of power by being in coalition with the ruling parties.

On multiple occasions, the left have reaped benefits of power by being in coalition with the ruling parties.

The authors thus envision and describe in details what they call a ‘NEW LEFT‘, which is “Not a separate organised formation with a distinct ideology but arises out of long and sustained struggles. It has no banners, blueprints, no charismatic populist or demagogic leaders”.

Also Read: Dawn Of A New Resistance: The Kisaan March That Shook The Country

Parting Thoughts

The selection of the themes and their organisation in this book emphasise a departure from both the despairing critics of the plethora of problems in India as well as from the ebullient accounts of the miracles of ‘India Shining’. Therefore, instead of dwelling on the much celebrated economic reforms or the much maligned political chaos, it engages with the building blocks of contemporary India.

However, too briefly described, for the attention it deserves, is the relationship between India and the world, in the last chapter with the same title. With the coming in of the early 90s economic revolution, the nuclear tests in the latter years along with several provisions of land grab are associated a number of international players. The book however wraps it up in a hurried attempt.

Also, the idea of ‘New Left’ is a hopeful one and smashes those critics who are full of analysis but with no direction forward. There is however, a need to fully explore this radical proposition. Several questions surround the mind, such as, “How does the ‘New Left’ establish it existence in a country governed by dominant political parties?”, “How does it break barriers of religion and caste?”, “What are the binding factors within this group, considering that it doesn’t focus on any blueprints?”.

On the whole, Power and Contestation is a fantastic attempt in providing a rich analysis of the political and economic reality of India as it moved rapidly towards global stardom. It also stimulates pertinent questions and thoughts that are relevant in contemporary times, more than ever before.