Posted by Dr. Sabreen Ahmed

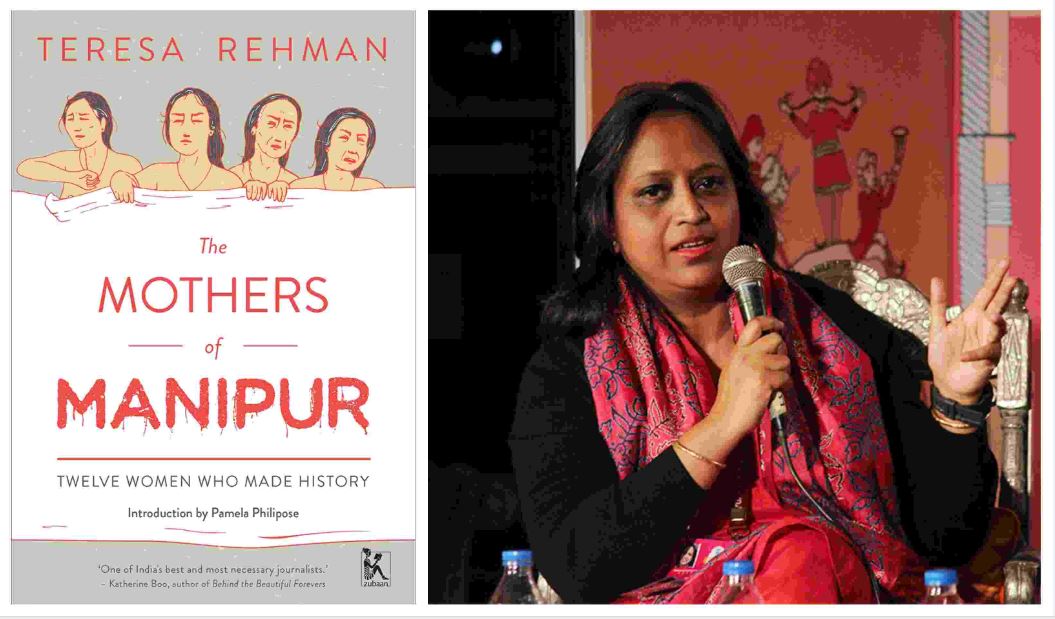

The Mothers of Manipur written by award-winning journalist from Meghalaya, Teresa Rehman is a blatant testimony of the culture of activism and gendered social organisation of the Meira Paibis or ‘female warriors’ of Manipur. The book is intricately weaved through the personal anecdotes of the painful oral narratives of the women interviewed in the book. It was published in March 2017 by Zubaan, an independent feminist publishing house based in New Delhi, an imprint of Kali for women, the first feminist press in India.

The oral narratives of the Imas, the local term for mother, serve as archival resources through their collective memories about the Nupi Lans or female wars of the past. The book also covers the present international glare at their unchanging predicament and the future of a hitherto peaceful Manipur surrounding the tales of the historic naked protest at Kangla Fort on 15th July, 2004.

Traditional anthropology and historical research used elders as informants and oral source materials of humanist positions and Teresa Rehman’s rhapsodic representation of the narratives of the ageing mothers is itself a feminist intervention in creating an archival text from a journalist’s pen. The book is a vivid tapestry of the ideas, beliefs and values that negotiate through the net of activist social relationships, journalistic interludes of the author with current public figures from Manipur. It also holds the heart rendering oral narratives of the twelve Imas or the mothers who unabashedly striped in front of the ASFPA headquarters demanding justice for the rape and mutilated murder of Thangjam Manorama, a 32 year custodial woman on 11 July 2004.

It holds the heart rendering oral narratives of the twelve Imas (mothers) who unabashedly striped in front of the ASFPA headquarters demanding justice.

Manorama was taken in custody without any proven guilt for a search operation on the night of 10th July and next day her body was found by her kith and kin in a mutilated position with bullet shots in her vagina. If the mutilated body of Manorama speaks volumes about the lust and inhuman atrocities of the coercive state machinery in the form of ASFPA, the naked bodies of the Imas speak the slogans of protest like “Indian army come rape us” against the vicious cycle of internal colonisation of a democratic republic vested in its armed forces.

Image Source: Outlook India

The folkloristic elements in terms of description of the Manipuri female dress phanek, the male garment Khudei, use of humais or hand fans and traditional food like the local samosa heikrak, and the fermented fish item iromba have been minutely detailed in the text that delivers a feel of the original to the reader. The narratives of the Imas or mothers, invariably shuttles between the stories of their kitchens to their tryst at the war zone that draws out of a time wrap the small voices of Manipur’s history.

These twelve Imas belong to diversified arenas of life – if Ima Matum is a shopkeeper, Ima Ramani is a traditional dancer and actor of the local courtyard theatre, while Ima Momom is a homely Kwa chaba or betelnut chewing grandmom yet a valiant Meira Paibi fighting against social evils from alcoholism and drug abuse to indecent frisking of women by security forces. Ima mema belonging to Vaishnavite faith is a septuagenarian with devotional mutterings in her narrative while Ima Nganbi is the only English speaking Mother.

The narrative of AIDs crusader Lucy precedes that of the devotional mother. Integrated to the narrative of Nganbi is the author’s personal repertory with the prolonged fasting convict Irom Sharmila, who muses over the poignant long poem in making, symbolic of her personal struggles. A woman who is featured in media with her uncombed hair like the fiery Medusa of Greek mythology is shown here as silently succumbing to resilience at the face of her singular fight for peace which eventually ended with the breaking of her fast in 2016.

Sharmila left her unpaid struggle, with ASFPA still unmitigated and etched in Manipur’s soil as permanent entity, with a promise to come back with political power for peaceful progress of her people. Ima Nganbi tells the horrors of the underground groups of Manipur from an insiders’ point of view that seems to support their cause. Their slogans like “Loilam leingak muthatsi” (We want freedom), “Ning tamna hinghallu” (Down with Indian Rule) resonate with their protest against internal colonisation in the midst of a draconian Act like AFSPA.

Also read: AFSPA: The Army’s Right To Rape, From Manorama To Karbi

The Manorama rape incident rather than being merely a feminist protest of sisterhood also provoked many emotions against the malfunctioning of democracy in India. The controversy of their outrageous protest and the lack of desired public empathy and their sentimental distraught led to Ima Nganbi’s remorseful statement “We did it for the people of Manipur, we are not prostitutes”.

A short interlude on the doyen of Manipuri theatre Heinsnam Kanhailal, the first from Northeast India to receive Sangeet Natak Akademy Award in 1985 for his alternate theatrical experimentations and his wife Sabitri who appeared nude on stage for Mahasweta Devi’s story Draupadi in year 2000 leads to the tale of Ima Ibetobi – an actor herself who once performed for the theatre group Manipur Dramatic Union.

A description of Urmila, a award winning journalist campaigning on menstrual hygiene makes way for the narrative of Ima Tombi, the youngest of all the mothers who runs a small eatery at Paona Bazar and had even gone to Delhi for protest against AFSPA. Ima Jamini positions herself as mediator after the protest hoping for a plausible solution beyond oppression and resistance from either side. The defying sisterhood of the Meira Paibies resonate in her narrative:

“Once we are out of the house and are with women, we don’t care about our family and mundane affairs. Ours is a community in itself. Ours is a community in itself. We don’t care what husbands, sons or our daughters-in-law will think”

the mutilated body of Manorama speaks volumes about the lust and inhuman atrocities of the coercive state machinery in the form of ASFPA.

A social activist of international repute and the founder of Manipur Women Gun Survivers Network, Binalakshmi Neprum’s narrative is linked to the narrative of Ima Taruni who recounts her memories of a difficult childhood with a garrulous father and later her fate with an alcoholic husband. Her existence intricately knitted between the threads of domesticity and activism the author fondly calls her “a time capsule” embedding in her 78 year old memory the changes in Manipur from a land of gems to a bloody state.

Next falls in line the personal journey of Lin, a model and actress who played the lead lady’s friend’s role in Bollywood film Mary Kom from which the narrative turns towards the tale of Ima Jibonmala who doesn’t wish to take side in connection to the UGs. The last two narratives describe the devotional Ima Gyaneswari and the forever absent mother for her daughter Ima Sarojini. The afterword in the book is the narrative of Manorama’s mother Thangjam Kunamleima, Khumanleima meaning “the princess of the Khuman clan” who became spectrally reticent after her daughter’s death remembers her eldest child ‘Mono’ as a good daughter and weaver who remained unmarried to bear the responsibility of her siblings said that her daughter’s soul will rest in peace only if the ASFPA goes away.

Phanek and enaphi a part of the folk culture of the Meitis, find political relevance through the nude protest. The traditional phanek and enaphi are considered sacrosanct for a Manipuri women and can’t be touched by a strange man. Pulling down the enaphi in collective resistance becomes a part of feminist ferocity no less than goddess Kali herself as one of the mothers draws an analogy towards the intending enemy which in this case was the state machinery itself.

The nude protest becomes sanctified as the Imas offer their prayers before plunging into the battlefield for the cause of retrieving their shame and social justice for Manorama who was cremated by the authorities as they declared her as an ‘unclaimed body’ when family refused to accept her body until the guilty were punished. The mythical content of oral literature is not the content of this reading because it talks about the lived realities of the Imas in their social activism which achieved panoramic furiousness with the Kangla incident with an unprecedented future of social justice for Manorama.

Also read: Book Excerpt: The Mothers Of Manipur By Teresa Rehman

Teresa Rehman amalgamates the gripping narratives of collective resistance of these elderly women all in their sixties or seventies against the assault on the collective honour of Manipuri women. The body as a troupe of defiant protest evading the norms of gentility, shame and sensuality, that the Imas used in all their nakedness of the march was a culmination of their mental angst repressed in their ‘collective unconscious’. The author confidently asserts in the preface:

“15 July 2004 will remain imprinted in every Manipuri’s heart. The iconic protest will continue to trigger debate and stand out in collective memory. It will always speak of the turmoil of people trapped in a world chock full of violence. It will always reflect the larger story of Manipur-a land torn asunder by conflict and brutality, but constantly exerting the might of its conflict and brutality, but constantly exerting the might of its cultural traditions and humane spirit, to triumph.”

The protest though a gendered one cannot be read in isolation with the customary Nupi Lan of the Manipuri community in an increasingly growing scene of ‘false consciousness’ after the coming down of the iconic activist, Iron Lady Irom Sharmila.

Nevertheless, the text is not without a few shortcomings in terms of conception. Rehman is absolutely silent about the political interventions in the aftermath of the protest. Nonetheless it takes remarkable courage as a female journalist in revisiting a traumatic memory in the insurgency rotten state of Manipur far away from communication comforts.

Also read: Irom Sharmila, AFSPA And The Quest For Freedom In Manipur

The non-linear, subversive manner of rhapsodising makes The Mothers of Manipur very much a manifesto of ecriture feminine or ‘feminine writing’ by a female journalist about the pains of other females. The book is undoubtedly a remarkable document in depiction of folkloristic ‘orality’ and the journalistic representation of the contested gendered history of Manipur in Northeast India.

Dr. Sabreen Ahmed is a writer and academic. She has a poem collection Soliloquies and an edited book Indian Fiction in English to her credit. She contributes essays to The Thumbprint, The Assam Tribune and Cafedissensus.

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.