A panel in The Hindu Lit for Life called Sexual Personae: Overcoming Prejudice and Misconceptions about Sexuality starts with the words “trans women are often seen on roads and trains harassing people” and “as a child, I found them frightening”. The woman uttering these words is Nandini Krishnan.

The other panelist, Madhavi Menon, says this “Does it make sense to have Pride marches in India when shame has not been associated with non-normative sexuality? In the Judeo-Christian background where sexuality is narrated largely, if not entirely, in the register of shame, the idea of Pride makes perfect sense. But when you are part of traditions in which shame, if at all is associated with sexuality, tends to be associated with heterosexuality, the idea of Pride doesn’t make much sense.”

Now I don’t know if Madhavi has heard, but no straight person has ever had to be ashamed of being straight or been prosecuted by the State for it. For queer people like me on the other hand, shame has been an intrinsic part of our identity for a long time. Pride parades help us overcome that and vocalise our personhoods.

Straightsplaining

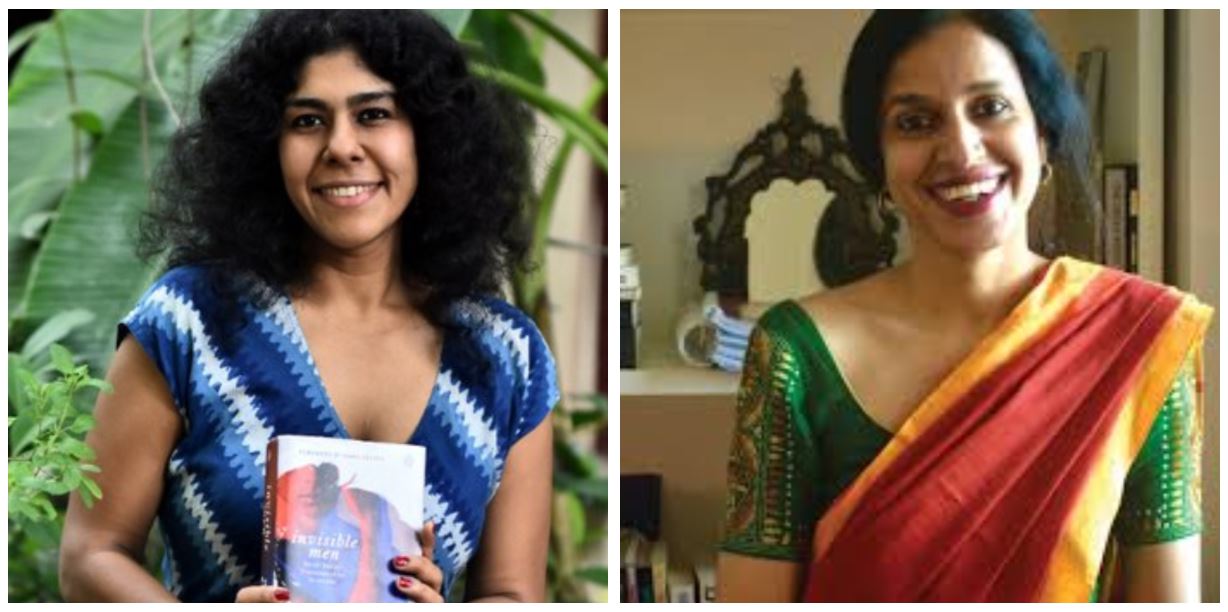

Nandini Krishnan is the author of the book Invisible Men: Inside India’s Transmasculine Network which “dissects and lays bare, in transphobic ways, the lives and bodies of the men with her voice-of-god narrative throughout”. Madhavi Menon is a writer and professor at Ashoka University. Half of her books are about queer theory but she still doesn’t seem to understand the innate emotions associated with being queer. Perhaps that’s because these women are straight, cis, and Savarna. It is beyond me why the organisers would choose to invite non-queer writers to a panel that is inevitably going to talk about LBTQIA+ rights, if not focus solely on that. There are several competent queer writers and it’s only logical that The Hindu invite and give a platform to them, instead of letting more straight people teach me how to be queer.

Marginalised people want to, nay, deserve to see their struggles and their stories being talked about on panels which claim to be for them.

This is called straightsplaining, and a very good way to understand it would be to watch panels discussing LGBTQIA+ issues which have actual queer people on them. The tone and narrative of these sessions is entirely different from the tone and narrative of a panel like Sexual Personae. At the very least, the first thing they talk about wouldn’t be how transgender people are considered “frightening”. This is dangerous, because marginalised people want to, nay, deserve to see their struggles and their stories being talked about on panels which claim to be for them. So when straight people show up in a space meant for you, a queer person, and tell you it makes no sense to celebrate the overcoming, or the process of the overcoming of your struggle, it hurts. It hurts and it is insulting.

It is dangerous because it contributes to the erasure of queer narrative. Worse, it replaces queer narrative with straight narrative wearing a rainbow mask.

“Pride Parades Are Unnecessary In India”

Let’s dissect a few of the the things these women say.

According to Madhavi Menon, “The idea of pride in the West arose as a rhetorical, political, emotional response to an all-pervasive atmosphere of shame. When you look at a situation like that, Pride makes absolute sense. When you look at the Indian context, the subcontinental context as a whole, this idea of shame is certainly by no means an overwhelming idea that we’ve had in relation to our sexual realities or sexual desires. Colonisation brought in the shame factor, yes, but the desi twist to that is people now assume it’s more shameful for heterosexuality to exist. If two women want to go on holiday together their parents would say ‘go for it’, but if an unmarried girl and boy want to go on holiday together, they’ll say ‘oh my god aren’t you ashamed?’. So it’s so interesting that it’s heterosexuality here that bears the burden and there are complex reasons for that.”

First of all, what?

If there is actually no shame attached to being queer in India, I would like Madhavi to answer why almost none of my queer friends have been able to come out to their parents. I would also like to know why homophobic and transphobic slurs in vernacular languages are existent and in wide practice. Pray tell me, Madhavi, why is marriage legally defined in India as “the state of being united to a person of the opposite sex as husband or wife in a legal, consensual, and contractual relationship recognized and sanctioned by and dissolvable only by law.”

If there is actually no shame attached to being queer in India, I would like Madhavi to answer why almost none of my queer friends have been able to come out to their parents.

The reason an unmarried heterosexual couple isn’t allowed to go on holiday together isn’t because Indians are afraid or ashamed of heterosexuality, Madhavi, it is because we are afraid and ashamed of sex. The reason that two women are allowed to go on holiday together is because we don’t even recognise homosexuality, and I don’t know how something can be degraded more than by deeming it unworthy of being acknowledged. So please, heterosexuality does not “bear the burden”.

She also for some reason keeps calling sex before marriage “non-normative sexuality” and I frankly don’t know how to comment on that.

“Labels Are Unnecessary Everywhere”

Something that both Nandini Krishnan and Madhavi Menon do is vehemently oppose categorisation and labels. They seem to be making the claim that it’s anti-progressive for queer people to so passionately want to label their sexuality or gender identity.

Also read: How Nandini Krishnan’s Book Hurts The Trans Men Community

Madhavi Menon, on the usage of labels, says, “What we’re doing is increasing the multiple sites of homogeneity. It implies you can either be straight or lesbian or whatever the five categories the State has recognised for you at that point. And I think there’s some real politics in saying ‘none of the above’, which is also a way of saying ‘all of the above’, which is also a way of saying ‘this in the morning, this in the afternoon and this the day after tomorrow’”.

As a confused queer teenager, when I finally found the vocabulary to describe my feelings and my identity, I wanted to hold on to it as much as I could. It helped me legitimise my personhood and I don’t appreciate being told that I’m wrong to do that. Also I’m sorry, Madhavi, but queer people don’t change sexualities throughout the day. I’m not straight in the morning and gay in the evening, I’m just bisexual.

I understand the queer people who don’t want to use any specific labels and I fully support them, but it’s not right to reprimand the ones who do want to use them.

“I Am Vegan So I Can’t Be Casteist, Sorry”

There were several other things said on this panel that we could dissect (although there is frankly nothing to dissect, it’s just plain hetero ignorance), but this diatribe shall end with a quote made by Nandini Krishnan during the panel about non-vegan queer people, “People who see themselves as oppressed would also believe in the oppression of animals. How could you be subjected to one kind of oppression and not be against another kind? I am vegan and the idea behind veganism is that all lives are equal so I don’t understand why people called me casteist when I said that it didn’t make sense to talk about Brahmanical patriarchy and the beef ban during Pride parades.”

Also read: The Hindu Lit For Life 2019: A Dearth Of Inclusivity And Representation

And this, Lit Fests All Over The World, is why we need to take an oath to invite only intersectional feminist queer people to queer discussion panels.

About the author(s)

Hamsadhwani is a law student and anti-caste socialist feminist. Abolish the conditions that produce the prison.

Section 377 is still not repealed – it has only been judged as unconstitutional – and yet Madhavi straightfacedly remarks that queer people do not face public humiliation. The myopia is astounding.