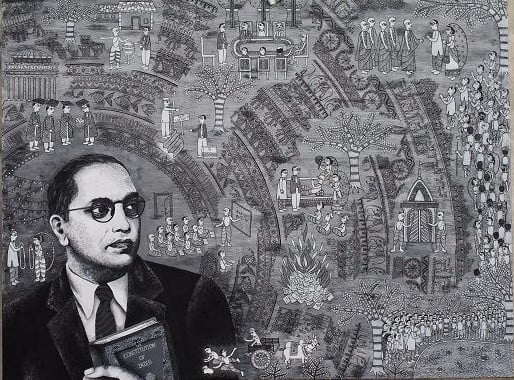

Malvika Raj is an artist from Patna who is making waves in the Indian art scene through her innovative twist to the traditional Madhubani artform, which is centered around Hindu narratives. She graduated from NIIFT, Mohali and has had her art displayed at several prominent exhibitions. One of her paintings, a Madhubani rendition of Babasaheb Ambedkar, is displayed at the University of Edinburgh.

Hamsadhwani Alagarsamy: Tell us a little about your art style.

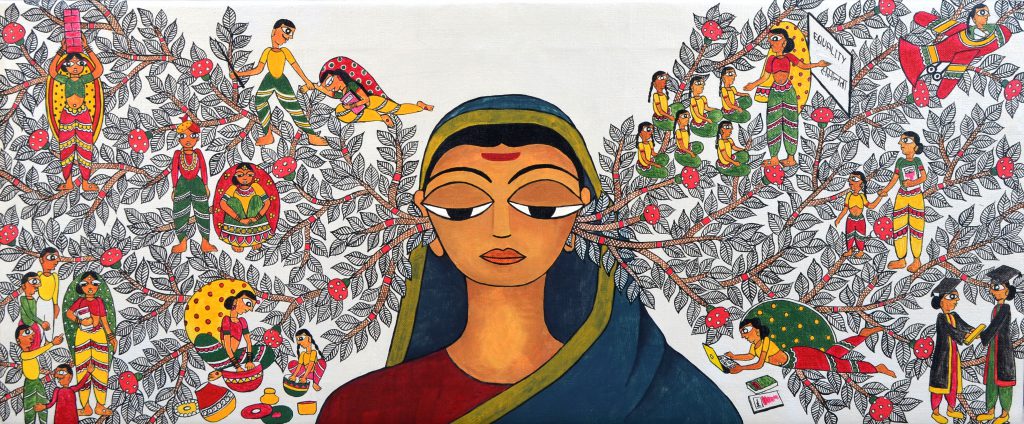

Malvika Raj: My art style is inspired from the typical Madhubani technique that originated in Bihar. The artform is essentially a way to tell stories from Hindu mythology. You will find most Madhubani paintings depicting scenes from the stories of Radha-Krishna, from the Ramayana and so on.

The subset of Madhubani style that I have drawn the most inspiration from is Kobhar. This style focuses on depictions of nature and was historically used to paint the mud walls behind the area where the bride and groom are seated during a wedding ceremony. If you look at my art, you will see the strong influence of nature. Also, Madhubani literally translates to ‘honey forest’. Madhu is Sanskrit for ‘honey’ and ban translates to ‘forest’. The art form as a whole used to be originally practised by forest dwelling people. It became dominated by Hindu narratives only after that.

With my art, I’ve tried bringing changes to this method by depicting the life and stories of Lord Buddha, Babasaheb Ambedkar and other revolutionaries close to my heart.

HA: What made you decide to subvert the traditional style of Madhubani paintings?

MR: When I started learning the Madhubani technique, the first painting I made was of Krishna. But I felt no connection to it at all, there was nothing for me to relate to. So I started to ask myself what my story was. What is it that would help me connect with my art?

I made my first painting depicting a scene from Buddha’s life, I knew that this is what made me feel content with my art.

My family has always been very political. Even when I was a child, my father would tell me about Buddha and Ambedkar and their ideologies and all that they’ve done for our community. Their stories have been a constant source of inspiration in my life. And so I decided that I would use this technique to tell their stories. Even then I wasn’t sure that it’s what I’d continue to do, but after I made my first painting depicting a scene from Buddha’s life, I knew that this is what made me feel content with my art.

Another incident that made me averse to depicting scenes from Hindu mythology in my art was something that happened on my trip to the Madhubani village. I had spent two weeks there, trying to learn as much about the artform as I could. It was overall a great trip and I enjoyed it immensely. But during my stay there I realised how much deeply caste differences have been incorporated even in art.

Historically, the Tantric subset of Madhubani art has been something that only the Brahmins have been allowed to work on. During my trip, I met a Tantric artist and when I asked him if he could teach me the style, he outright refused because I’m a Dalit. When I replied to him saying that I could just study the technique enough and teach myself the artform, he said bad fate would befall me. Caste is so deeply entrenched in everyone’s minds that even a local Dalit artist asked me not to paint in the Tantric style because he feared for my life.

There are other silly differences too. For instance, the double line technique is supposed to be used only by Brahmins and the single line technique only by the Dalits. The Godna form of Madhubani is also practised only by Dalits.

All of this made me decide I wanted the art I create have nothing to do with any Hindu structures. I decided to paint the stories that inspire me. That’s what made me paint my first series, called ‘The Journey’, which tells the story of Lord Buddha’s life.

HA: What was the public’s response to your dissident paintings?

MR: People generally have not been very welcoming of this Ambedkarite transgression to the traditional style, because even my depiction of Buddha has been from an Ambedkarite lens. I’ve removed most of the mystical, Hindu-esque portions from Buddha’s story in my art series.

But one incident that I’ll never forget took place at one of my exhibitions in Patna. A man completely dressed in saffron, without even properly going through my paintings, came straight to me and said, “this is not Madhubani art. What have you done?’

I was extremely annoyed and did not even want to engage with him but I asked him how he could say it wasn’t Madhubani when my technique was right and I had done storytelling as well. He replied with “There is not a single depiction of Hindu gods and even your portrayal of Buddha doesn’t contain his avatars.”

This is a small incident but it was quite infuriating and very impactful in my understanding of caste politics when it comes to my art.

HA: What was the inspiration behind your inventive painting of Babasaheb Ambedkar that is currently displayed at the University of Edinburgh?

MR: Again, it was my father and his words that inspired me. On both sides of my family, I am the only artist and thus my father has always been very supportive and encouraging of my inclinations.

I was talking to him about the Madhubani artform and how it is a storytelling tool. He said it sounded like a great way to teach people from our community about Ambedkar and other revolutionaries. A major proportion of Dalits in our neighbourhood aren’t educated and art could serve as a great way of bringing these stories to them. That’s what made me decide I had to paint Babasaheb in the way I knew best, through Madhubani.

HA: As a Dalit woman, did you find it harder to establish yourself as an artist, considering art is a field dominated by upper-caste people and narratives?

MR: Exactly! It is indeed immensely dominated by upper caste people. I did find it very difficult to establish myself and I find it hard to be in this field to this day. I feel immensely alone a lot of times. I mean, apart form the people in my community and organisations like FII, very few people really care to appreciate me or include me in events.

There are artist groups within each art form and location but I feel systematically excluded from all of them. I work all alone. It’s not even like the other artists don’t know of me and thus haven’t been able to reach out. It’s 2019, we all know of each other through social media. They just choose to sort of levy an embargo on me.

There are artist groups within each art form and location but I feel systematically excluded from all of them.

Other reasons for this exclusion could be that I didn’t initially have a fine arts background. I had majored in fashion designing and only about a couple of years ago did I get a fine arts degree. Also, the government does not recognise my art as Madhubani. They’ve categorised it as contemporary. But the artist circles believe it is Madhubani and that there is nothing contemporary about it. It’s a very problematic position to be stuck in.

HA: Dalit art has so far not been recognised as a separate category. What are your thoughts on this?

MR: I don’t really care if Dalit art is officially recognised or not. I just want a Dalit art movement. I want it to be highly impactful and I want it to reach several people.

I mean, we are going to keep making art whether it is acknowledged or not. How will them recognising it even make a difference to us? What matters to us is we’re creating ripples, and I think we’re well on our way to doing that.

I personally don’t think they have any intention of recognising it any time soon, but our art is powerful and they will have to acquiese at some point. For how long can they deny and exclude us?

HA: Do you think all art is political?

MR: When I’m making art, it comes from my heart. When a singer sings, it’s from her heart. It’s not political until then.

But the moment another person consumes that art, the lens he consumes it from, that’s what politicises the art.

For example, the painting of Savitribai Phule that I made, that came from my heart. I read about the astounding work she has done and it inspired me incredibly. That’s what made me paint it. I didn’t intend it to be a political stunt or something. But when someone else looks at it, the political angle would inevitably come in.

3rd January 1831, the birth date of Savitribai Phule , also known as SavitriMai Phule, is a day which is currently celebrated as the “Teacher’s day” among Dalits and Bahujans in India. Savitribai, played an important role in improving women’s conditions and became the pioneer of women’s education here.

But this is just my opinion based on personal experience. I’m not someone who knows a lot about this.

HA: Your art has been featured in countless diverse exhibitions. Is there an experience you particularly enjoyed?

MR: I was part of this very cool exhibition once. It took place in Jehangir Art Gallery in 2012.

There was this small boy, probably just three or four years old. His mom had her art installed on the floor below me but he’d always come to my part of the gallery. The exhibition was on for seven days and he would go through each of my exhibits at least once, every single day. He would spend hours just staring intensely at each painting. He looked so focussed and content.

This is again a very small incident but it is incredibly close to my heart.

This is not related to exhibitions, but I’m forever grateful for all the love the poeple from my community have been showering upon me, and all the appreciation and exposure that organisations like yours have provided me.

HA: Are there any other projects you’re involved in?

MR: So apart from being a Madhubani artist, I’m also a fashion designer. I’m currently working on a project which fuses these two skills of mine – a Madhubani styled clothing line. My fashion brand is called ‘Musk Migi’. Migi translates to ‘deer’ in the Pali language. I have trained close to 30 Dalit women in Madhubani and they are all employed by me. Under this project, we’ve conceptualised sarees, bags, bangles, and other garments.

I’m also working on a couple of painting series.

There is another idea I’ve had for a long time that I haven’t been able to start work on. I want to release a children’s book with Madhubani paintings on each page depicting the life of Babasaheb. It will also have a few words describing the painting and telling his story. It has been a dream of mine to do this for quite a few years now, and I hope to be able to do it soon.

Also read: In Conversation With Cynthia Stephen: Dalit Activist, Journalist And Writer

FII thanks Malvika Raj for taking out time to do the interview and for sharing her beautiful artwork.

About the author(s)

Hamsadhwani is a law student and anti-caste socialist feminist. Abolish the conditions that produce the prison.

An NGO in Danapur [district Patna], I recall, in 1990s had encouraged Musahar women for Self Help Group [SHG] for dealing in packaging of rice and selling in packets to local as well as Patna markets, thoug not far off place for the area of operations. The initiative took off well and soon.

But then the rivalry of others, targeting the SHG of Musahar women came into fierce action. The caste occupies the lowest rung of hierarchy of Bihar.

Slowly and gradually the demand for the rice came down and ultimately they were forced to wind up the venture!

Sad, very sad.

I hope our young artist Malvika Raj has the courage and ambition to stand up to every viccititude on her way. Then will she win the day. Best of luck to her.

How to buy your art

Just saw her painting ‘mai’ on google arts and culture page. would like to see more of her art. please share her social media profile

Glad to see such talent. Would be nice to know more about her. YDW best wishes to Malvika. May u shine more 🙂