Mai was originally written by

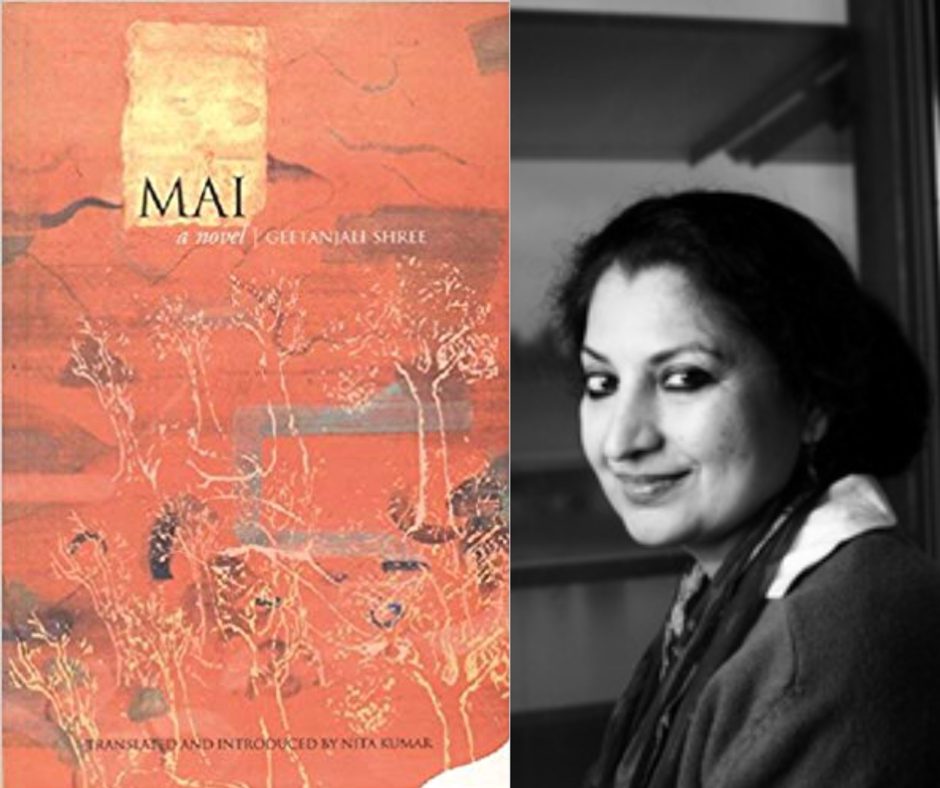

Book: Mai: A Novel

Author: Geetangali Shree (translated by Nita Kumar)

Publisher: Zubaan, 2000

Genre: Fiction

The novel traces the story of Mai and her children, Sunaina and Subodh’s attempts to save her. Set in a North Indian household, Mai is babu’s wife, dada and

Even though both siblings love their mother unconditionally and want the best for her, they are not able to view their mother outside of her role as the wife, daughter-in-law and mother – which is the biggest concern the novel poses. Sunaina paints Mai as the seminal victim of a patriarchy-oppressed society. From the start of the novel Mai is shown to be powerless and weak:

“We always knew mother had a weak spine. The doctor told us that later. That those who constantly bend and get this problem… have pain all the time: pain when they bend, and pain when they stand up straight.”

Mai. Nita Kumar. Page 1.

Her weak spine is used both as an expression of her submissiveness and a medical ailment. Sunaina and Subodh metaphorically claim their mother has a weak spine, but this is scientifically reinforced by the doctor’s confirmation on her physical body. As a result of having a ‘weak spine’ in both its meanings, Mai is constantly in pain which also symbolises her powerless existence. However, the question raised is ‘Is Mai completely powerless or is there a kind of power even within silence’?

Through the motherhood of Mai, the novel explores the ambivalence associated with womanhood in India: a country of all-powerful divine mother goddesses and equally powerless human mothers. However, it is the word, powerless, that Shree urges readers to consider in Mai.

Sunaina’s narration of Mai is restricted to ‘inside’ the home, where the other family members all exercise power over her. Mai possesses the ‘quality’ of silence, the only thing

“We could start evaluating silence differently than how our dichotomous, rationalist world, much like Subodh and Sunaina’s, tells us to. We could question agency, strength, and weakness anew. We could take the plurality of each of these things seriously”.

Mai. Nita Kumar, 168-169.

The novels projects Mai as the image of a docile wife, obedient daughter-in-law and self-sacrificing mother, and in relation to these roles a powerless and oppressed woman. Shree subtly probes the reader into questioning the image of Mai visualised through Sunaina and the possible ‘other’ Mai which may have gotten lost in motherhood.

Sunaina exclaims that “Mai was always bent over. We should know. We’ve been watching her from the beginning. Our beginning is her beginning after all.” This reiterates the idea that Mai’s beginning is only the children’s beginning and that before becoming a mother, Mai still existed – but we are never given insight into that person, except that she was called Rajjo before marriage. Thus, Kumar highlights the paradox of the mother as:

“Both weakness and power, innocence and manipulation, self-denial and

Mai. Nita Kumar, 162.self interest . It is the paradoxical reciprocity of the two that creates a version of the master-slave dialectic, that leads to confusion on the part of observers, and miscalculation by both ‘oppressors’ and ‘reformers’. Mai goes to the heart of this paradox.”

Readers can unravel this paradox through Sunaina’s narrative. Firstly readers are presented with an interpretation of Mai from the perspective of Sunaina’s and Subodh’s

Mai, despite her silent suffering, challenges the patriarchal control over her children as she has more influence over them. Sunaina explains how every member of the family, except Mai, tried to restrict her and put her behind purdah. She attributed this to Mai not paying attention to her, but it is evident to the reader that Mai did this on purpose. Mai knows how to discipline and regulate her children’s behaviour.

Also read: Book Review: Vanmam – Vendetta By Bama

Sunaina confesses, her mother’s trust instilled solemnity in her – something dada’s patriarchal authority,

It was Mai’s conscious decision to not force her will or the family will on her children and shape them into patriarchal identities.

It was Mai’s conscious decision to not force her will or the family’s will on her children and shape them into patriarchal identities. She nurtured her children to have their own viewpoint and beliefs, encouraging them to be self-willed beings, that are not influenced by existing conventions. Due to the narrative being told through Sunaina’s eyes, Mai has the most profound effect on Sunaina, who is not misled by the established notions of femininity – from the existent purdah that she was being forced into by the society, but Mai “pushed the curtain open before it could be stretched shut and closed tightly.”

This was Mai’s mode of challenging the male-controlled hegemonic system that had forced her to remain in purdah. For Mai, motherhood was a powerful identity that it empowered her to bring up her children, two individuals, who questioned the conventions of the male-dominated society explicitly, in a way that she could not.

Mai did not lose her children to a societal system where her children would become self-sufficient and independent from her, but is able to conserve a level of intimacy and close relationship even after they leave the house. At the end of the novel, Sunaina becomes a painter and returns home, and Subodh goes abroad. Both siblings inhabit spaces differently – Sunaina does not marry and leave the house and Subodh does not continue the cycle of patriarchy.

Mai is a smooth read which does not force you into thinking or feeling a particular way,

Also read: Book Review: Motichur Volume 1 & 2 By Begum Rokeya

The novel includes an appendix by Kumar with the sections ‘The Matter of the Mother’ and ‘History, Anthropology, and Mai’ unequivocally devised to elaborate Shree’s sociological exegesis, which is a treat particularly for literature students. Mai is a feminist novel that speaks to mothers and daughters universally, especially relevant to Indian readers who can relate to the novel on a personal level.

Featured Image Source: ArtZolo

About the author(s)

Nikhat is a Civil Servant and Communications Manager for BBPC Poetry Collective. Her academic research interests include wartime gender-based violence and intersectional feminist historiography.