Trigger warning: Abuse, Sexual misconduct

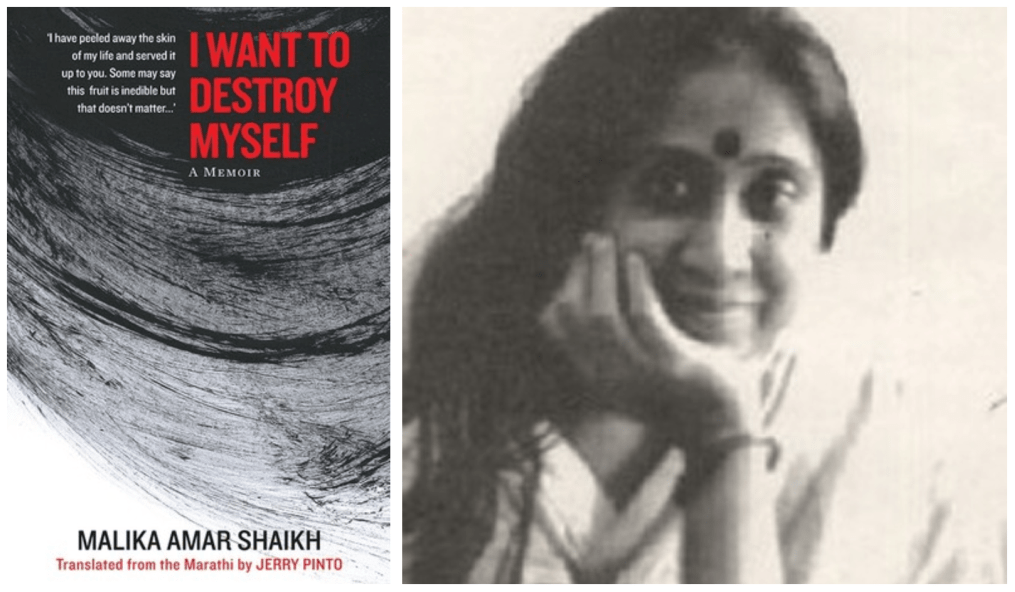

“It is customary to say that one has enjoyed the process. I did not enjoy translating Mala Uddhvasta Vhaychay. It would often leave me feeling somewhat in danger of collapse”, says Jerry Pinto in his translator’s note to I Want to Destroy Myself by Malika Amar Shaikh. If Shaikh has read Pinto’s words, I believe she would have been moved beyond words – a man had not only attempted to understand her suffering, he had translated it to English (from Marathi), helping her to exert her voice to help those who brave abuse and present a facade of happiness.

Here is a translator who understands Shaikh’s plight – she doesn’t demand pity or sympathy by weaving out the fabric of her abusive marriage; she doesn’t shy away from speaking out her mind, from criticising her husband, Namdeo Dhasal, founder of the Dalit Panthers, meant to fight caste discrimination, and most importantly, she is unafraid to be unabashedly herself even if her opinions seem controversial, of reclaiming her identity from simply being Namdeo Dhasal’s ‘wife’, of destroying herself in order to recreate herself. First published in 1984, Shaikh’s book quickly disappeared after much acclaim. Yet, she has come alive once again in English, bitterly and consciously commenting on her experience, without distinguishing the personal and the political.

On Marriage, Motherhood and Being a Woman

“Ninety-five per cent of women who say, ‘My married life is going rather well’, are telling lies”, asserts Malika Shaikh. As an adolescent, Shaikh was curious about womanhood, about the relationships that develop between men and women. So when Namdeo Dhasal came into her life with his crudeness and playfulness, she felt utterly charmed. The romance of the moment swept her off her feet and she passionately agreed to marry Dhasal at the age of 14, despite staunch opposition from her elder sister.

It is from here on that Shaikh begins to unravel the deep-seated inequality between men and women. Dhasal playfully forces her to have sex with him before marriage, and she feels nothing else but pain. She deliberately blurs the line between consensual and forced intercourse, leaving the readers wondering whether she was raped or not. She completely refuses being put on a

Also read: Book Review: Vanmam – Vendetta By Bama

She marvels at Dhasal’s mother, who can give her husband and son unconditional support, something she is unwilling to do. Shaikh criticises her in-laws, confesses her lack of desire to care for them, and eternally battles abject penury, for Dhasal refuses to provide for his own family. She finds it both amusing and annoying how people assume their right to be served a meal while at Dhasal’s home, how they refuse to contribute in any manner and how they desert her when she needs them the most. She is unceasing in her dislike of being a wife and a homemaker, and longs for a partner who encourages her, treats her with respect, and doesn’t give her STDs due to his extramarital affairs.

She longs for a partner who encourages her, treats her with respect, and doesn’t give her STDs due to his extramarital affairs.

Shaikh’s most poignant thoughts, however, are about motherhood. Suffering from labour pains that leave her almost unconscious, she sharply comments on how she cannot feel transcendental love for her son after experiencing pangs that almost kills her. The filthy condition of the bathroom wrecks her, and slowly, she begins to understand ‘motherhood’ as a theory formulated by men. Even after she became pregnant 3-4 times, Shaikh refused to have those babies. She no longer wanted to bear such agonising physical pain when Dhasal rarely cared. Abortion becomes her only exit and she unflinchingly ‘gives up her femininity’ in order to survive.

Despite her aversion, what is interesting to note is her perception of childhood. She understands how important it is to encourage the dreams of childhood, and continuously fights for the well-being of her son, even attempting to legally fight Dhasal. Yet, one can see how she prioritises her own safety over spending time with her son – when things become abusive, she leaves Ashutosh with his father. At another time when Ashutosh witnesses Dhasal beating her, she internally gloats at her son’s desire to hit his father.

Motherhood then becomes a concept Shaikh keeps negotiating with – she actively attempts to mould her son into a human being; at the same time, she refuses to give in to ‘unconditional love’, knowing that her individuality extends much beyond than identities like wife and mother.

On Politics, Caste, and Religion

“What have you to do with it? What do you know”, asks Dhasal when Shaikh disapproves of his tie-up with Shiv Sena. Despite marrying at an early age and leaving her education incomplete, Shaikh demonstrates an intrinsic understanding of human psychology. Her observations about her husband’s political career are astute. Without apprehensions, she reveals how Dhasal lacked proper skills to effectively organise a strong movement like the Dalit Panthers, how he opportunistically used his persona and oratory skills to tie-up with those who were unceasing in their praise, how the fight against caste discrimination existed only in the background, something that allowed Dhasal to occupy the role of a politician.

She distinguishes his identities, asserts how she fell in love with Dhasal, ‘the poet’, someone who fit in with her idea of how a man should be. Her dreams and her reality differ greatly, and she openly questions and criticises Dhasal for his wasteful ways, for his lack of concern about his family, for his flimsy attempts to assuage her after he’s maniacally beaten her. Shaikh is able to

What is even more interesting is Shaikh’s stance towards religion. Born to parents who were members of the Communist Party, and who married each other outside of their religion, Shaikh asserts that she is a ‘humanist’. She feels uneasy when she is forced into a job interview reserved for Scheduled Tribes for it contradicts her beliefs and gravely admonishes her husband who wishes to worship Buddha’s statue on their son’s birthday after a suggestion because she understands how Buddha himself did not advocate for such measures.

She doesn’t attempt to make herself likeable, constantly generalises situations, refuse to don the garb of the quintessential wife, and openly asserts her dislikes.

She keenly observes how caste brings men together even when they support different camps. However, through a series of narratives about women from a different class, caste and religion, she showcases how women are treated almost similarly by men, suffering from abuse and lack of care, almost to dehumanising extents. Her questions examine situations that still plague us, and to which she finds no solution. Her questions, enquiries and observations lead her to an interesting definition of what liberation means for women: “The woman who knows where to stop is a woman of independent mind.”

Shaikh then demonstrates an intuitive grasp of nuances, understands how the intimate and the public are not two different realms of existence and how education isn’t the only measure of intelligence. Her writing is simple, disjointed and even borders on being didactic. Yet, her memoir holds importance for asking the most basic questions about women’s rights and women’s writing, questions lost in the inertia of debates.

She doesn’t attempt to make herself likeable, constantly generalises situations, refuse to don the garb of the quintessential wife, and openly asserts her dislikes. But in a world that constantly looks at her as Dhasal’s ‘wife’ who married him out of ‘choice’, Shaikh doesn’t restrain herself from asking for help; she admits to her brokenness, her inability to love unconditionally (even her own child), her flaws, and her desires openly, without worrying about judgements.

Also read: Book Review: A Life Less Ordinary By Baby Halder

Despite her suffering, Shaikh animatedly confesses her desire to live, even in a world where ‘human’ rights, above all else, will never fully be realised. Such individuality isn’t simply empowering; it is an important assertion of self-identity with the recognition that storytelling can be an enabling and therapeutic form of freedom.