Married at 15, a mother at 18, and widowed four months after she had given birth, the odds were stacked against A Lalitha. However, her determination to make a life for herself and for her daughter prevailed. Lalitha became the first Indian woman engineer. She was a trailblazer for the brilliant women who were and continue to be inspired by her success story.

Early Life

Lalitha was born on August 27, 1919 in Chennai, into a middle-class family. Obligated to conform to the social norms back in the early 1900s, Lalitha got married as a 15-year old teenager. However, her parents held a strong belief in education, and insisted that she continue her studies even after she was married. She went on to obtain her Secondary School Leaving Certificate (SSLC or Class X), and this was initially thought to be enough. Four months after giving birth to her daughter, her husband passed away. Widows at the time were not treated well in Indian society, so Lalitha was severely disadvantaged.

she resolved to carve out a meaningful and full life for her and her daughter.

However, she resolved to carve out a meaningful and full life for her and her daughter. She thought about becoming a doctor, as many women were doing so at the time, but decided that the rigours of the profession would prevent her from effectively taking care of her child. Her other option was to become an engineer. It did not occur to this bold woman to limit herself to professions that were already opened to women – engineering was a strictly male-dominated industry in those years. Thus, her journey to becoming India’s first female engineer began.

Education

Lalitha completed her intermediate exam with first class at Queen Mary’s College. She was then ready to get a professional degree, and wanted to join the four year electrical engineering program at the College of Engineering, Guindy, University of Madras (CEG). Dr Shantha Mohan’s book Roots and Wings: Inspiring Stories of Indian Women in Engineering recognises the accomplishments of women graduates of CEG such as A Lalitha.

Lalitha was a brilliant student, but technical training was seen as an exclusively male sphere, even in the late 1930s. Luckily for her, Lalitha’s father, who had been a professor of electrical engineering at CEG, pleaded her daughter’s case to the principal, Dr. K. C. Chacko, who agreed to let her onto the program. These two men were the first to put their faith in her and were a significant part of her success in a misogynistic education system.

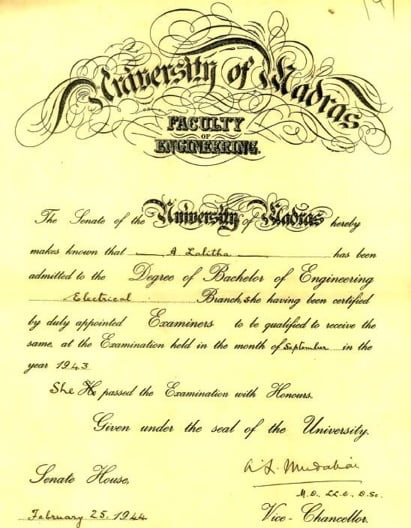

Lalitha, the daughter of a professor and the sole woman on campus, attracted the scorn of many of her classmates. While she had managed, in theory, to penetrate a male space, forming a camaraderie with male students who had not expected to be studying alongside women was not easy. Her father, noticing his daughter’s plight, once again stepped in as her male, privileged ally. He put out an ad for more budding female engineers to join CEG, which led to PK Thresia and Leelamma George being admitted into the college as well. The presence of the two other women made Lalitha feel more comfortable at CEG, a testament to what female solidarity can do. She received her Bachelor of Engineering degree in 1943. The completion of her education marked the beginning of her new life.

The presence of the two other women made Lalitha feel more comfortable at CEG, a testament to what female solidarity can do.

Career

Fresh out of college and ready to start working, Lalitha took a job offer as an engineering assistant at the Central Standards Organisations of India, Simla. This job allowed her to balance single parenthood and working life admirably well, as she was able to live with her brother’s family and enlist the help of her sister-in-law in looking after her daughter. She stayed in this job for two years before leaving to help her father with his research. Lalitha father’s had several patents, including smokeless ovens and an electric flame producer, so she was not short of intellectual stimulation while working with him. However, due to financial difficulties, she had to move over to Associated Electrical Industries, in Calcutta. As with her last job, she had to find a male member of her family to move in with – a widow living alone would have been considered a problem in those days. She lived with her second brother while working at AEI in the engineering department.

Also read: Rupa Bai Furdoonji: World’s First Female Anesthetist | #DesiSTEMinist

By this time, Lalitha had become known as the accomplished engineer that she was, and while she was at AEI, she was enlisted to work on big projects such as Bhakra Nangal Dam, the biggest dam in India. She mostly worked on designing transmissions lines, and other times, on protective gear, substation layouts, and execution of contracts. Through her excellent work at AEI, Lalitha gained even more attention from the engineering community, both locally and internationally.

Through her excellent work at AEI, Lalitha gained even more attention from the engineering community, both locally and internationally.

Achievements And Highlights Of Her Work

Lalitha was a brilliant engineer with a relentless spirit, and many organisations began to acknowledge that. In 1953, the Council of the Electrical Engineers, which is based in London, invited her to be an associate member. A few years later, she became a full member. The most celebrated and documented achievement of her career was being invited to the First International Conference Engineers and Scientists (ICWES) of 1964 in New York. Unfortunately, there had not been an Indian chapter in the conference, so Lalitha had to attend it in private capacity. Subsequently, Lalitha became involved in international organisations for female engineers. Her trip to a British factory was covered by several newspapers, and female-oriented magazines published many interviews with her. She also became a member of the Women’s Engineering Society of London in 1965. Lalitha continued to speak up for women in engineering until she passed away from a brain aneurysm in 1974, when she was only 60 years old.

A group of women who attended the First International Conference Engineers and Scientists (ICWES) of 1964 in New York. Left to right: A. Lalitha, Joan Shubert, unknown delegate, N. Sainani and Dee Halladay.

A Multi-Faceted And Inspiring Woman

Throughout her incredible career, she managed to stay committed to raising her daughter, Syamala, and made the necessary sacrifices for her as a single mother. Syamala has said in interviews that she never felt the absence of her father because Lalitha was so dedicated to her upbringing. On top of being a gifted engineer and a loving mother, Lalitha was also a spokeswoman for widows in India. When she made her speech at the ICWES in 1964, she famously said, “150 years ago, I would have been burned at the funeral pyre with my husband’s body”.

Throughout her incredible career, she managed to stay committed to raising her daughter, Syamala, and made the necessary sacrifices for her as a single mother.

Lalitha proved to the world that she could overcome social barriers, but also created opportunities for other women to do the same. She promoted the second ICWES in India, encouraging more Indian women to attend – five others joined her at the conference that year. She understood the importance of building up other women around her, and provided inspiration for her fellow female engineers. Today, there are still three times more male engineers than female in India, and the industry continues to prove difficult for women to enter. This is why A Lalitha’s legacy is still important; her example continues to provide hope to women who wish to follow in her footsteps as engineers in India.

Also read: Charusita Chakravarty: The Chemist Who Fought Sexism In STEM | #IndianWomenInHistory

References

- Mohan, Shantha. 24 May 2017. The First Woman Engineer in India. All Together. Retrieved from here.

- The Hindu

- Blush

About the author(s)

Beverly Devakishen is a final year student at the University of East Anglia studying Literature and History. She is interested in Asian history, as well as issues around gender and sexuality. She is deputy editor for The Queer Review and has done journalism internships at newspapers such as The Guardian.