The most recent Lok Sabha (17th) session witnessed the highest number of women ever in the Indian Parliament, with 78 women MPs elected from all over the country. Women’s representation in the Lok Sabha has increased from 11.3 percent in 2014 to 14 percent in 2019, coming across as a positive development. However, the diversity composition within the group of elected women candidates needs further analysis on the lines of caste, class, religion and ethnicity. Adding to this, these numbers are also significantly lower in India than its neighboring countries like Nepal (32.7 percent), Pakistan (20.2 percent) and Bangladesh (20.7 percent). The relatively stronger representation of women in these countries is due to the implementation of legislated gender-based reservations. This increased representation of women in politics is seen to grab local, national and global attention on issues of violence against women and grow awareness around sexual harassment and mental trauma.

THE BILL CERTAINLY LOOKS PROMISING IN ITS ATTEMPT TO ACKNOWLEDGE THE INTERNAL COMPLEXITIES WITHIN THE CATEGORY OF WOMEN BY RECOGNIZING THEIR RESPECTIVE DEPRIVATION POINTS DERIVED FROM CASTE INEQUALITIES.

It is about time that we move beyond a general cry for women’s empowerment and try to look outside our assumed sense of homogeneity with respect to the category of women. In the context of the Women’s Reservation Bill or The Constitution (108th Amendment) Bill proposed on 06 May 2008, by the UPA-I government, that remains pending till date in the Indian Parliament, the proposition to have one-third of all seats reserved for women in the Lok Sabha and the state legislative assemblies was a sincere concern aimed at increasing the representation of women in these male dominated spaces. The same Bill also seeks to reserve one third of the total number of seats for women from Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. However, reservations for women from Other Backward Classes (OBCs) has not been incorporated within the Bill, despite receiving recommendations from the Report examining the 1996 Women’s Reservation Bill. The reservation policy is said to be discontinued 15 years after the commencement of the Amendment Act.

The Bill certainly looks quite promising in its attempt to acknowledge the internal complexities within the category of women by recognizing their respective deprivation points derived from caste inequalities. Such a Bill would ensure that their specific narratives, concerns and modes of oppression are voiced out in the public sphere, which otherwise receives very little attention. This lack of attention mostly results due to two major reasons -one, that only a section of the privileged, upper caste, urban educated women occupy the few spaces available for women, and two, within the existing framework of general reservations, the privileged among the underprivileged, that is the men within these socially deprived groups are able to find more opportunities of education and employment than the women.

It is of little surprise, that women’s empowerment and their intersectional forms of oppression often get subsumed within the general, tokenistic political discussions. Adding to that, most of the major political parties do not encourage women’s issues to be a central political theme in their campaigns, unless a physically or sexually violent matter such as rape, or domestic violence is highlighted in the media. Further, it is also important to understand how “women’s issues” are often relegated within the sphere of the private, whereas their socio-economic marginalization is systematically invisibilised or selectively visibilised within mainstream politics. For instance, women’s empowerment revolves around issues of reproduction and marriage, but their socio-economic conditions of employment, education and health rarely in politics. Such systematic invisibility diverts our attention from larger structures of oppression such as the state, to more immediate oppressors like the patriarch of the family. The lack of representation of women in powerful positions in the Lok Sabha or the legislative assemblies hinder the focus required on women’s education and financial independence, that may have helped them to break free from oppressive familial ties. This is not to trivialize everyday forms of oppression within the family. It is to stress on the idea that not only the category of women is internally heterogeneous, but the antagonisms and challenges that they face in their everyday are also multiple.

The proposed Bill therefore would be an entry point to raise such questions of the politics of intersectional deprivation within the category of women. However, one cannot ignore but notice the exclusion of OBC women from the proposition. Although, post Mandal Commission, the specific issues of OBCs have been voiced in different spheres, it certainly did not eradicate the gender hierarchies within the backward classes. Research has also depicted that among the OBCs, the Muslim OBC women are further deprived due to various intersections of oppression inflicted by religious and caste discrimination.

The lack of representation of women in powerful positions in the Lok Sabha or the legislative assemblies hinder the focus required on women’s education and financial independence, that may have helped them to break free from oppressive familial ties.

The BJP manifesto that was released before elections by the party has included the Women’s Reservation Bill on page 32, item 14, which promises that, “Women’s welfare and development will be accorded high priority at all levels within the government and the BJP is committed to 33% reservation in Parliament and State Assemblies through a constitutional amendment”. However, this promise has remained unfulfilled by several other parties in the past.

Also read: India Needs More Women In Parliament And Here’s Why

Ahead of the first Lok Sabha session of 2019, about 270 civil society activists have written to the Indian Law Minister, Ravi Shankar Prasad, urging him to “draft a proposal or revise the old draft of the Women’s Reservation Bill”, which had lapsed multiple times in the past three decades. With the rising concerns over the decreasing labour force participation rates and the increasing number of cases of violence against women, the country and its women are looking forward to the upcoming Lok Sabha sessions.

Tara Krishnaswamy, the co-founder of Shakti, issued a statement after the first Lok Sabha Session saying, “Shakti is keenly looking forward to the Parliament sessions and welcomes new Parliamentarians. The ruling party has promised to execute a constitutional amendment to deliver the Women’s Reservation Bill. And we hope they will keep up their promise. We are also excited that many other parties, including the opposition have added it to their manifesto, passed it as their resolution in state assemblies and have raised it in their all-party meeting, asking the BJP to make sure that the Bill is tabled and passed. We think that there is an unprecedented momentum towards this and we plan to keep up all the public pressure that we can. We invite all fair minded citizens – women, men and all genders, to join Shakti in this campaign. This will be a campaign joining hands with many organizations and individuals in the country, under the common umbrella in improving democracy in India.”

Despite the deplorable track record of the proposed Bill, one could only hope for better representation in various legislative bodies to address these concerns promptly and more effectively.

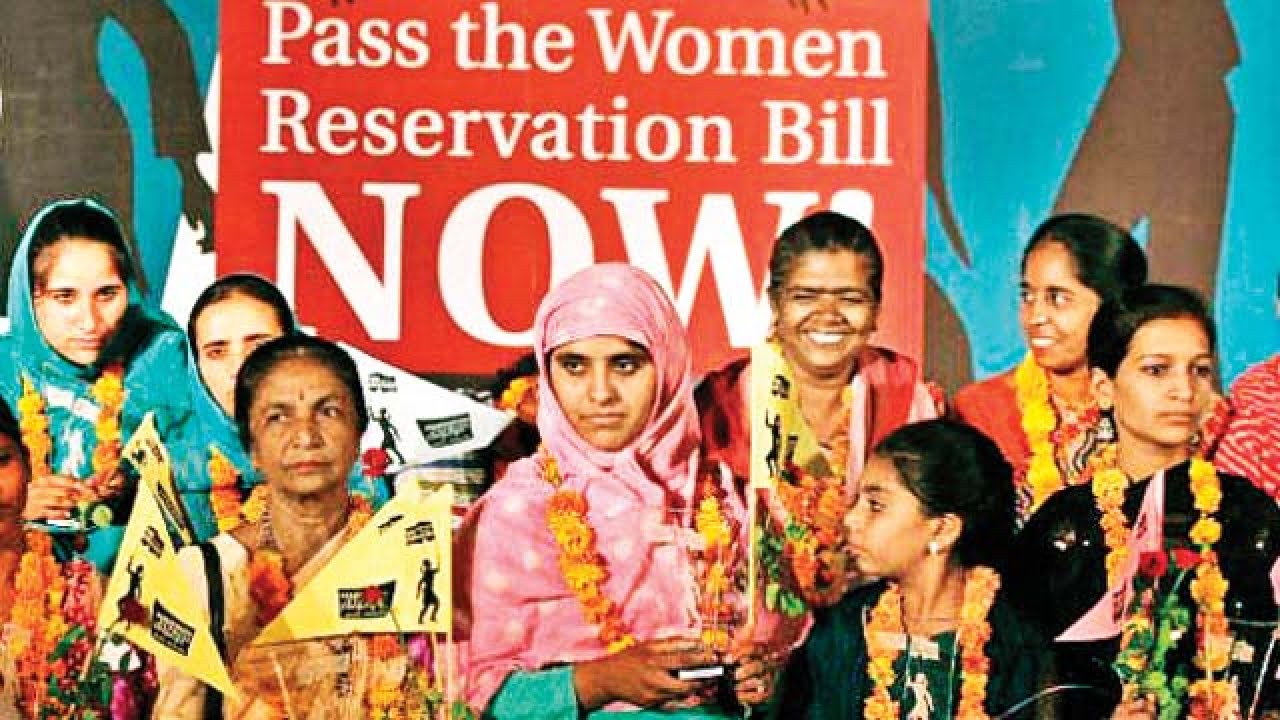

Featured Image Source: DNA India

About the author(s)

Pragya is a Master's Graduate in Sociology from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She works as the content editor at Feminism In India. She is also a ramen enthusiast, a hummus mother, a postcard hoarder and a wannabe cat lady. She still prefers writing on her notebooks, rather than on her laptop, but her job demands her to do just the opposite. Her favourite season is spring, and her alter ego is that of Mrs. Dalloway who said, "She would buy the flowers herself", in case no man ever buys her any!

Well written! Congratulations Pragya:)