The Chipko resistance is one of the most meaningful social attempts to right a power asymmetry, born out of a spontaneous rural outburst that spread through Northern India, creating waves in its wake in the 1970s-80s.

Society is built on power imbalances and wherever there are power imbalances, there will always be conflicts. Social movements are one of the primary channels to express these conflicts and create some sort of structural equilibrium. The Chipko resistance is one of the most meaningful social attempts to right a power asymmetry, born out of a spontaneous rural outburst that spread through Northern India, creating waves in its wake in the 1970s-80s. Its distinctive character becomes all the more important when one analyses the pivotal role that women played in making the movement a success.

The real roots of the Chipko movement go back to 1730, when Amrita Devi led the movement to resist soldiers from cutting down trees, on the orders of the Maharaja of Jodhpur, in her native Khejarli village. In the ensuing violence, 363 members of the Bishnoi tribe were beheaded as they hugged the trees to prevent them from being cut. The news of the massacre made the Maharaja pass a decree, disallowing the felling of trees in the area, and left two unforgettable legacies behind—the value of collective protest and the importance of women in local resistance. Using Neil Smelser’s six stages structural strain theory, one can discern the imminent causes of the Chipko movement, literally ‘to hug’ in Hindi, and its growth.

Stage I: People in society experiencing some sort of problem

Villages in Uttrakhand were experiencing severe ecological strain due to the unsustainable extraction of resources by the government. In a continuation of a colonial practice that began in 1821, the government systematically began to close off more and more forest area from the natives. It gave contracts to private companies who ruthlessly withdrew forest goods without a thought to the long term effects, which the locals kept in mind while utilizing forest resources.

Large scale clearing of trees for the building of roads had left the area prone to disastrous landslides which devastated the community. Government programmes for development, such as in education and health, did not exhibit the desired results and the condition of the locals remained poor. There was a clear incompatibility between government interests, which were exploitative in their profit-oriented drive, and local interests, which depended on forests to survive

Stage II: Recognition by people of that society that this problem exists

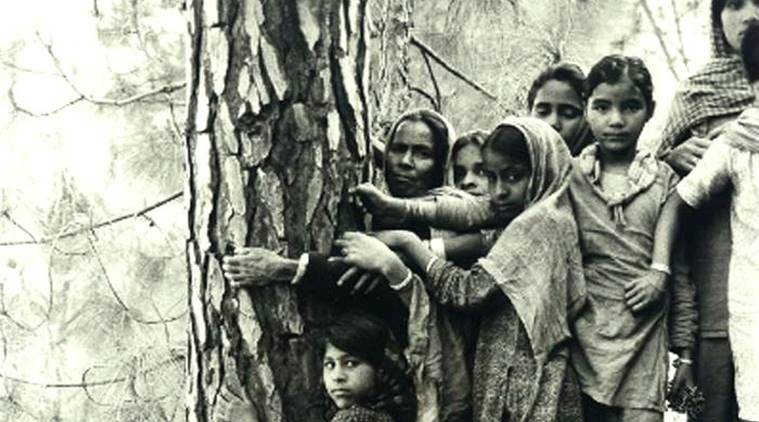

Women were particularly vulnerable to government channelled private bleeding of resources due to the unique social circumstances in the area. A significant proportion of households in the area were single-member female ones and the demographic was biased in favour of females. There was also large scale male migration, which meant that the responsibility of running the household fell on the women.

The gendered division of work prohibited them from ploughing farmland, but they actively weeded, planted and harvested it. Collection of forest materials for sale, such as honey, or for subsistence, such as firewood, was also a largely female-driven process, making their very survival indelibly tied to the natural ecosystem. They recognized the relationship between the environment and landslides relatively early on, and in the face of increasing resource scarcity, allied with the men to protect their forests.

In a continuation of a colonial practice that began in 1821, the government systematically began to close off more and more forest area from the natives.

Stage III: An ideology purporting to be a solution for the problem develops and spreads its influence

For the women, the movement became about conserving as well as challenging a norm. They wanted to protect the environment, preserving its state. Simultaneously, they questioned the status quo, biased in favour of men, and demanded a say in decisions which affected them. Eco-feminism became an important factor in the development of the movement, emphasizing as it did the relationship between the exploitation of nature and the suppression of women.

Also read: Six Women’s Movements From The North East That You Should Know Of

Stage IV: An event or events transpire that convert this nascent movement into a bona fide social movement

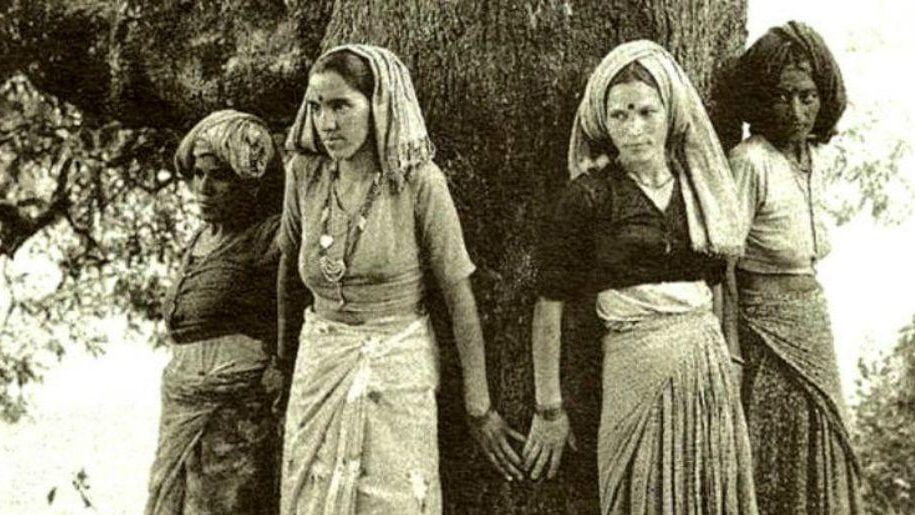

The modern movement was triggered in 1973 in Uttrakhan’s Chamoli district and restricted itself to non-violent measures to express dissent. The immediate cause was the allotment of an entire ash tree forest to the Simon Company for commercial purposes. The same forests had been petitioned for by the villagers to make their agricultural tools, but had been denied. The allotment to the private company inflamed the furious locals further and on the day allotted for felling, they came out in large numbers to fight for their livelihood and subsistence.

They sang folk songs and clasped the trees, daring officials to fell them. Despite the brutality they faced, they refused to give up and eventually the company retreated without a single tree being felled. In the ensuing debates, the Forest Department finally agreed to let the locals use the ash trees, after cancelling its contract with the Simon Company. The success of the resistance bred the Chipko movement, which became an acclaimed means in the area to safeguard local interests.

Collection of forest materials for sale, such as honey, or for subsistence, such as firewood, was also a largely female-driven process, making their very survival indelibly tied to the natural ecosystem.

Local leaders such as CP Bhatt and Sunderlal Bahuguna began propagating the cause and mobilizing the villagers, yet the large role the women played in the movement is somewhat ignored. A careful analysis reveals that the Chipko movement is largely based on spontaneous demonstrations where these leaders were absent, and there were very few organized protests.

Gaura Devi and Sudesha Devi are two popular leaders in a large sea of women overshadowed by their male counterparts who played an equally important role in securing forests rights and protecting the environment. In 1974, the former led the women against local loggers who appeared to fell trees, when the men were negotiating with the government for land compensation. Refusing to be daunted, Gaura Devi referred to the trees as her ‘maika’ (mother’s home) and invited the loggers to shoot her instead of harming the forests.

Ultimately, the loggers were forced to withdraw from the Reni village in the face of the mass demonstration by the women. Similarly, Sudesha Devi spearheaded the women’s drive to protect the Rampur forests from contractors, going as far as to spend nights amongst the trees to shield them from abuse and destruction.

After initial successes, the movement developed a gendered split most evident in the example of the Dongri village. The Horticulture Department came to an agreement with an all-male council in the village which allowed them to fell trees in the area in exchange for a cement road and secondary school, among other things. They believed that the development of the village was more important than the protection of the trees, which was in complete opposition to what the women believed. The threat to their subsistence prompted the women to go against the men in the village and protest the felling, forcing the company to withdraw. This polarized the movement and the women were subsequently banned from village meetings but they persisted to safeguard their interests and conserve the environment.

The lack of support from the community also gave the Chipko movement a distinctive tinge in fighting against familial oppression. They saw the movement as a means to assert their freedom, and it also broadened into a movement against alcoholism at one point. The Chipko resistance became an umbrella movement to conserve the environment, fight the private sector and government and resist patriarchal norms.

Stage V: The society (and its government) is open to change for the movement to be effective

There were several wins in the protests that took place especially in terms of government acquiesce to popular demands. A notable concession included a fifteen-year governmental ban against felling trees in the Himalayan region till the forest cover was restored. It is believed that the Forest Conservation Act (1980) and subsequent creation of the Environment Ministry were due to the pressure created by the Chipko movement.

THE CHIPKO RESISTANCE BECAME AN UMBRELLA MOVEMENT TO CONSERVE THE ENVIRONMENT, FIGHT THE PRIVATE SECTOR AND GOVERNMENT AND RESIST PATRIARCHAL NORMS.

Stage VI: Mobilization of resources takes place as the movement develops further.

The non-violent means of protest employed received international acclaim and the widespread involvement of women brought Eco-feminism to the foreground in worldwide conservation debates. Mahila Mandals became important local networks to ensure proper usage of forest resources and gave women an additional path to organize and affect decision making about matters that concerned them.

The dwindling of the movement can be attributed to several factors. The polarization between the Bahuguna and Bhatt camps of conservation and the lack of support from the Communist Party of India are among them. The region that birthed the Chipko resistance is now ironically littered with ped kato (cut the tree) activists. Yet, the importance of the protest cannot be undermined because of its present day decay the importance of non violent social movements and women’s participation remain timeless legacies of the Chipko movement.

Also read: 5 Prominent Indigenous People’s Movements That Hit Back At The State

References

- Eco India

- Times Now

- India Times

- Down To Earth

- Shobhita Jain. ‘Standing up for trees: Women’s role in the Chipko Movement’ (1984)

- Anindya Sen. ‘Why Social Movements Occur: Theories of Social Movements’, (2016)

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism in India