An ordinary morning for most women in India would be tangled and cluttered in getting their children ready and off to school or college, stepping aside so husbands can get ready and leave for work, and often feeding and helping aging parents and sick relatives. If lucky enough to have house maids, women lay out their chores for the day and supervise them as well. Women who themselves work do all of the above, in addition to getting themselves ready for their own job responsibilities. Many women also run the gamut of grocery shopping, paying bills, settling accounts at the bank, keeping children’s medical appointments, attending parent-teacher conferences, taking children for tuition, helping children with their homework, making social visits and any number of other responsibilities.

A World Bank study indicates that India’s female labor force participation stands at 27% compared to 96% for men. Women, disproportionately, are engaged in unpaid work at home and the outside. While women of each generation find opportunities for greater and varied labor participation, it would not be inaccurate to say that women in general, face greater challenges in finding and keeping gainful and satisfactory employment. Women also face greater obstacles in defining and claiming their relationship to their professions with the same degree of dedication, satisfaction and pride with which men own their paid labor.

The three films from three different regions of India in three different languages discussed here provide a prophetic and resilient vision of how women have negotiated and claimed their economic and existential worth in a society that is all too ready to deny them the opportunity to discover their own autonomous personhood through work.

Women’s troubled relationship to compensated labor, and thus their own autonomy, share a history of resistance against certain types of deeply rooted patriarchal norms characteristic of all societies across the length and breadth of India. The three films from three different regions of India, in three different languages discussed here, provide a prophetic and resilient vision of how women have negotiated and claimed their economic and existential worth in a society that is all too ready to deny them the opportunity to discover their own autonomous personhood through work.

Two Films And A Common Theme Of Solidarity

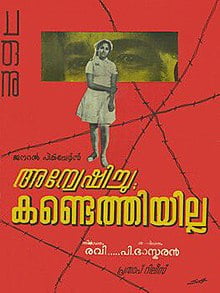

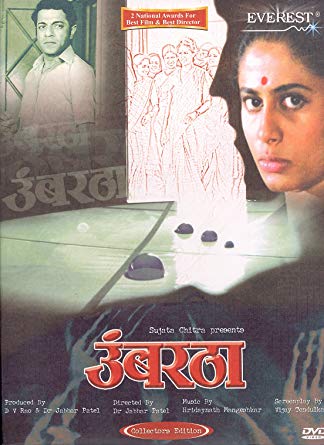

Both Satyajit Ray’s Bengali film Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963) and P. Bhaskaran’s Malayalam film Anweshichu Kandethiyilla (I Searched But Did Not Find, 1967) were released in the same decade—the former telling the story of a young married woman from a genteel family fallen on hard times in Kolkata in the 1950s, and the latter narrating the story of a bright young woman from a Christian family in Kerala in the 1950s.

In Mahanagar, based on a story by Narendranath Mitra, Madhabi Mukherjee plays Arati Mazumdar, a sprightly young wife, mother and daughter-in-law in a traditional Bengali household who decides to break the family’s principle—”a woman’s place is in her home“—and take on the job of a salesgirl for a company that sells knitting machines. Susamma, played by the Malayali actress K. R. Vijaya in Anweshichu Kandethiyilla, likewise, decides to become a nurse in the military to offset the financial hardships of her family.

Both Ray and P. Bhaskaran artfully expose the social prejudices, not only against women entering the labor force, but also women working at certain specific jobs. In the time period in which the films are set, in the 1950s, both being a door-to-door salesgirl as well as a nurse were not seen as professions suitable for “good” women. These were jobs that necessitated women to go into unknown areas and mix and mingle with unknown men. Of course, these strictures were placed upon women by a patriarchal code of honor, chastity, mobility and modesty.

Image Source: FirstPost

Arati’s husband Subrata, played by Anil Chatterjee, is at first supportive of his wife taking up the salesgirl’s job, but soon he finds himself resenting his unsuspecting wife, as his own insecurities at his inability to find a better-paying job begin to fan the flames of a competitive jealousy within him. Ray expertly shows the bitterness contracting Subrata’s demeanor as he watches his mother serve his wife breakfast alongside him in the morning as they both get ready to leave for work, or when Arati comes home with presents for the family when she gets her first month’s salary. Subrata turns away petulantly in shame and jealousy at the clear evidence that his wife, his efficient “housewife,” is equally efficient at work and has even received a commission on top of her salary! Underneath the vows and the intimacies or lack thereof, a marriage is an economic partnership, and a family is an economic unit. Man is the head of this unit in patriarchy’s version of the story.

In Anweshichu Kandethiyilla, Susamma becomes the head of the family as she lovingly accepts the responsibility to take care of her aging uncle and aunt who had fostered her after her own mother had died, and her father and his wife had cast her out. If married women had to ensure that they did not earn more than their husbands did and always stayed a step behind and not tarnish the glow surrounding their husbands, unmarried women found their single status itself to be a burden in the workplace.

Both Ray’s film and P. Bhaskaran’s film in the 1960s assert solidarity with working women in the characters of Arati and Susamma… Susamma stands up for herself. Arati stands up for Edith.

Based on a story by the acclaimed Malayalam writer Parappurath, P. Bhaskaran’s film explores the baseless prejudice Kerala had against nurses from the Christian community; often, young single women who traveled far and wide, all over the country and the world, worked and took care of their families, and served as exemplary examples of the nursing profession. Susamma’s brother refuses to accept a watch she sends him, and once again, imitating Subrata in Mahanagar, he commands Susamma to quit her job.

Also read: Fishing For The Hidden Feminist Agency In Kumbalangi Nights

He fears social disapproval of her nursing profession, and the disapproval staining him as well. A potential groom tells her that he will marry her if she would keep the fact that she had been a nurse, a secret from his family and friends. Susamma stands adamantly against these irrational demands. Befitting an educated and progressive woman, Susamma tries to find a partner herself. It is instructive that the two male romantic interests of Susamma are both cowardly and weak men who Susamma ultimately rejects. Susamma has to choose between her profession and dreams of a family. She chooses her profession.

Both Ray’s film and P. Bhaskaran’s film in the 1960s assert solidarity with working women in the characters of Arati and Susamma. Arati’s decision to quit her job when her boss insults her colleague, a young Anglo-Indian woman named Edith, after slandering her character (“Anglo-Indians girls like to have fun“) is an unforgettable moment in the film. ‘Apologize to her‘, Arati tells her boss. ‘It is a big world, we will both find some job, won’t we?,’ Arati asks her husband, who was also newly unemployed, and who finally admits and admires her courage to stand up for justice. Earning our daily bread has made us cowards, Subrata tells her, but you are brave. Susamma stands up for herself. Arati stands up for Edith.

Umbartha (The Doorstep, 1982)

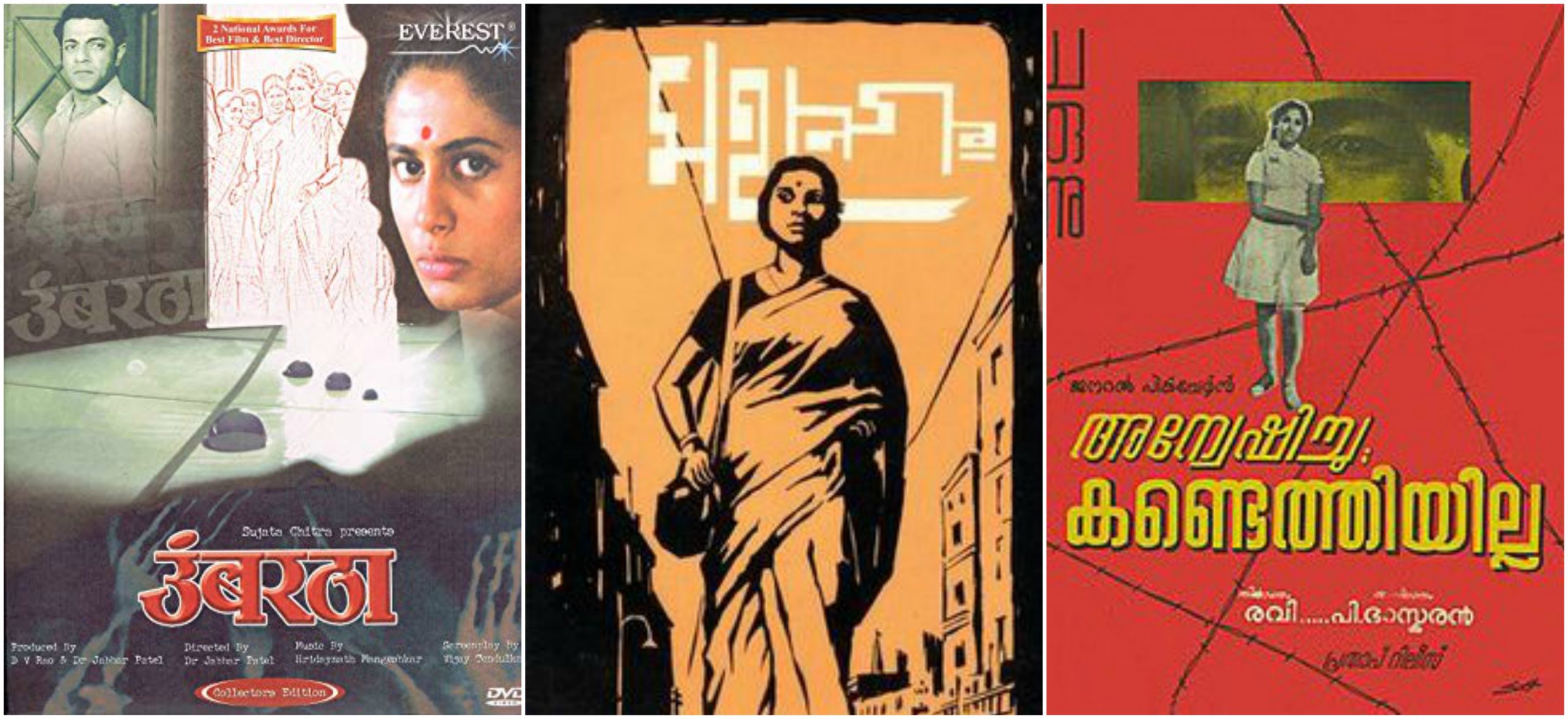

Women standing up for oneself and for other women in both private and public life is reprised in Jabbar Patel’s Marathi film Umbartha (The Doorstep, 1982), which was also simultaneously made into the Hindi film Subah (The Morning). Based on the Marathi writer Shanta Nisal’s story Beghar (Homeless) and scripted by the Marathi playwright Vijay Tendulkar, Umbartha is the story of Sulabha Mahajan, a thoughtful young wife and mother, who wishes to escape the gilded cage of a loving marriage with a carnal husband and affluent in-laws.

Sulabha, played by the Marathi and Hindi actress Smita Patil, eventually convinces her husband Subhash, acted by Girish Karnad, to let her go to the village of Sangamvadi to take on the job of the superintendent of a women’s reformatory home. Living in the midst of abused, sick, unwanted, cast out women, Sulabha instinctively understands that even the most comfortable woman is just one unknown step away from being homeless, as she institutes changes in the women’s reform home, and the women’s home makes changes in her.

As with the professions of nursing and salesgirl, being a social worker in an abused women’s home is not where women of “sound mind” work, according to Sulabha’s husband, her in-laws and the people who know her. Why worry about these women who nobody wants? The most “good”, that women can do for such places is to serve as a member of the board or management. While Umbartha does have its limitations for an eighties film, especially in its treatment of lesbian sexuality, it admirably and boldly exposes the dangers awaiting professional women who put themselves in the frontline and show solidarity with other abused and exploited women. Sulabha’s husband goes back estranged from her when he visits her at the reform home. She stops him when he accosts her for a quick shag while an inmate bleeds to death in the hospital from premature labor. Sulabha carries her own homelessness within her like a talisman; she finds her home with the other homeless women. This is not a tragic ending, but a clear awakening.

Also read: 4 South Indian Movies That Start A Conversation About Caste

Susamma, Arati, and Sulabha. Decades later, these women still give voice and face to scores of Indian women who grapple with the true object of their attention: themselves, their work, and the others.