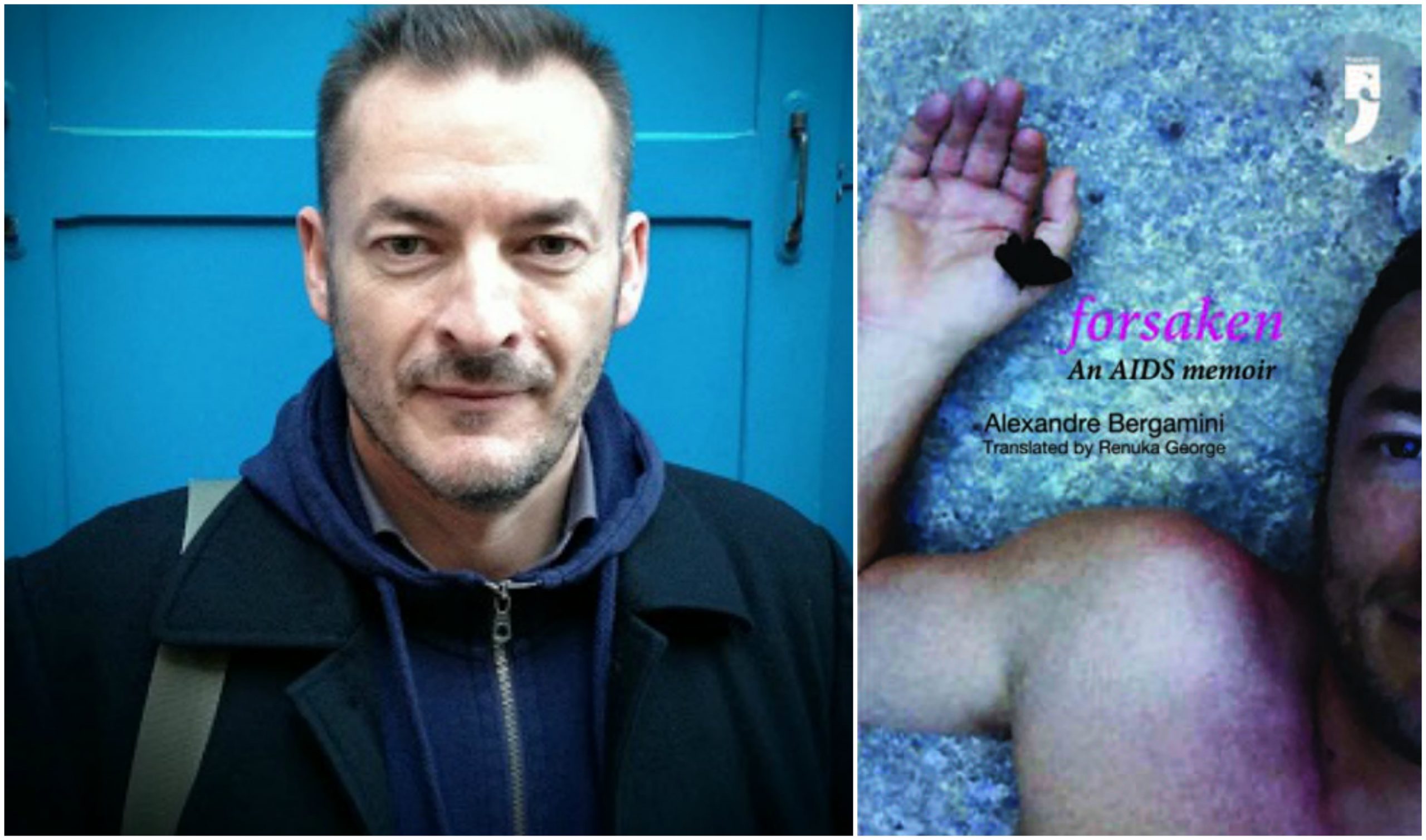

“It is not sexuality which haunts society, but the society which haunts the body’s sexuality.” — Maurice Godelier. This line by Godelier in Forsaken: An AIDS Memoir best serves the function of this book for me. In its eloquent translation in English by Renuka George, this memoir by the French author, and a poet, Alexandre Bergamini examines what it means to be homosexual and seropositive; and serves as a reminder for our society that continues to stigmatize people who have AIDS, especially, for those who think that it’s a “gay disease.”

Forsaken: An AIDS Memoir

Author: Alexandre Bergamini

Publication: Yoda Press (2015)

Genre: Biography

Reading Forsaken: An AIDS Memoir will give you a feel that you’re reading a series of vignettes as some sort of a diary entry. Last when I read something that had semblances with the sense of isolation, trepidation and making-sense-of-one’s-own-being life was reading The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank, which was also a collection of diary entries.

In these vignettes, Bergamini in Forsaken: An AIDS Memoir, takes us through the profound inquiries that one must make. These inquiries range from immediate ones to far-fetched debates concerning every socioeconomic and political construct and puts the marginal and dilapidated lives of people having AIDS in the spotlight.

Structure Of The Book

Being a collection of vignettes doesn’t mean that this book doesn’t have a structure. It does. Divided in three part — bucketing several private events that happened between 1968–1997, 1997–2006, and after 2006, and juxtaposing them with the social reality in France — Forsaken: An AIDS Memoir takes us through the author’s internal dilemmas and struggles: social stigmatization (because he’s gay), love (instable relationship), tragedy (brother’s suicide), and internal transformation (new perspective for life during and post-treatment of AIDS).

Affected by the politics that gave rise to the hatred among people toward homosexuals and people having AIDS, and appalled by the lack of material published on AIDS for general awareness purposes, he reminds us of how the LGBTQIA+ community is overlooked time and again, discriminated since ages.

Beginning with, what Bergamini describes, his unwanted birth, to his brother’s suicide, to his relationship with his parents, he comes out as someone negotiating this cruel world unarmed and often bruised. Bruised with words such as this by his father: “I will bury all of you.” Affected by the politics that gave rise to the hatred among people toward homosexuals and people having AIDS, and appalled by the lack of material published on AIDS for general awareness purposes, he reminds us of how the LGBTQIA+ community is overlooked time and again, discriminated since ages. However, according to him, homosexuals do serve a purpose for people, as he observes, for there are people who want to police our sexuality. He writes, “Homosexuality is permitted when it contributes to the wealth of the country.” And when cops regularly raid public places determined to “‘cleaning up’ Paris,” describing the then contemporary situation in France “as if the homosexuals who do not see themselves as ‘gay’ were garbage.”

“Today, men have forgotten the struggle concealed in the depths, between the conscious state and the body, as it arises in courage, particularly in physical courage. We generally see awareness as passive, while the acting body would constitute the essence of everything that is boldness and audacity. However, in the drama of physical courage the roles are, in fact, reversed. The flesh cautiously retreats to adopt its defensive role, while it is the decision taken by perfect awareness that makes the body soar by renouncing itself. The exquisite clarity of awareness is one of the factors that contribute the most actively to self-renunciation,” Bergamini writes.

How Our Society Controls Our Sexuality

Two outstanding achievements of this work is its commentary on the shallowness of societies — be it East or West. Firstly, their make-believe system that what they consider is “natural” and, hence, acceptable. Bergamini writes, “A sexual disease is an excellent way for society to control its citizens. To control sexuality is to control revolt. Disease makes every man his own censor.” And how can society control our sexuality? By being armed with misinformation, as provided by state-sponsored machineries, and these agents of hatred succeed in their mission as this misinformation is happily accepted by our society. For example, this comment by one of his neighbors, “It’s better to be a fascist than gay.”

Also read: Book Review: Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices Of Queer Diaspora By Gayatri Gopinath

Secondly, what remains at the heart of this memoir is the complicity of the medical arm of the state machinery in France that led to the metastasization of the disease AIDS into an epidemic.

He writes, “[W]ith the tacit agreement of all those involved, they took the decision to continue in silence to distribute the infected blood to people who had undergone operations, accident victims, the sick or haemophiliacs. It was not a mistake but a sordid calculation based on financial interest. When the last infected batches could not be disposed of in France, they were distributed and sold to ‘friendly’ countries.”

What makes Forsaken: An AIDS Memoir more relatable to the contemporary situation in India is the fact that despite the reading down of Section 377, that criminalized same-sex consensual relationship among adults, homosexuality is still considered something ‘queer’ – in the pejorative sense of the word. A remark by Moussa, a dancer whom Bergamini met during his voyage to different places, says that Bergamini is not a homosexual, but “killing time before [getting] married.” This is the proof of how people perceive homosexuality — having flings with boys or men before settling for a girl or a woman.

What makes Forsaken: An AIDS Memoir more relatable to the contemporary situation in India is the fact that despite the reading down of Section 377, that criminalized same-sex consensual relationship among adults, homosexuality is still considered something ‘queer’ – in the pejorative sense of the word.

However, he’s not only quick to remark but intelligent in his response for his reader to note the fact that it’s not only those societies that don’t understand, or rather don’t want to understand or accept homosexuality are regressive, but western societies too are characterized and “methodically standardised by men, white, heterosexual, tax-paying. And seronegative [people].”

“I have just turned twenty-nine. Seropositive and homosexual. Double jeopardy.” – Alexandre Bergamini

Striking a chord with a recent passing of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, 2019, back home, Bergamini’s observation of transphobia is spot on. He recalls, “In February 2010, transsexuals cease to be considered psychiatric patients as homosexuals were prior to 1982. However, they are still not officially recognized, not is transphobic violence. Most incidents are closed without any follow-up by the police.”

Also read: Book Review: Love, Loss, And Longing In Kashmir By Sahba Husain

Struggling with all this amidst his own personal battle against the disease, toward the end, Bergamini finds life to be cherished as is. He seems to be making music out of the situation when he leaves us with a hope, a meditation for himself, but it’s well applicable to all of us, “Living is a therapeutic act. Reconciled, repaired would my writing cease to be fragmented? Would I no longer write? I know the gulf created by the inexplicable and the incomprehension of those who never encounter anything like this: neither confrontation with a mortal disease, nor sudden loss or the suicide of a family member, the closest. This knowledge is not a wound.”