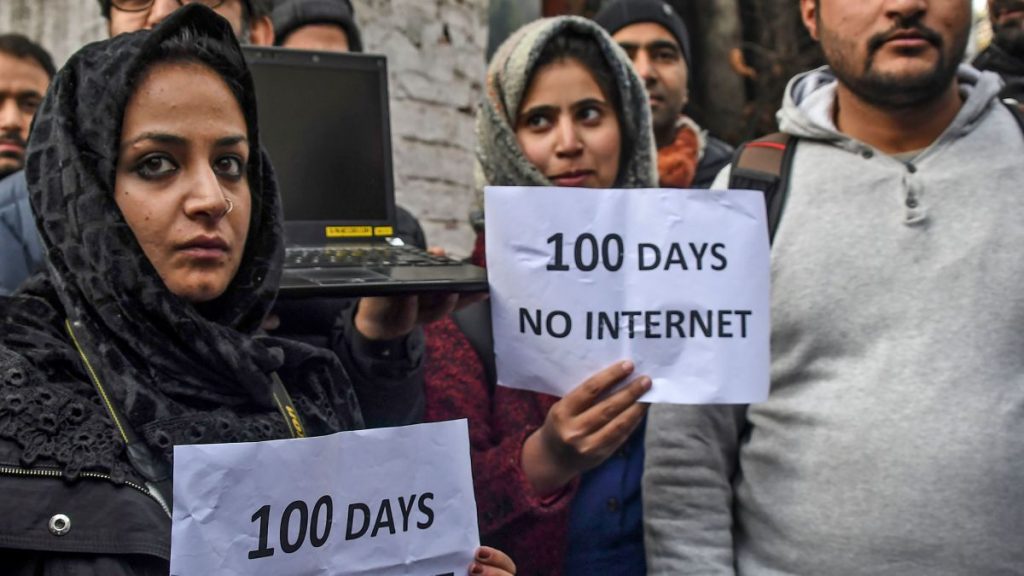

On January 19, 2020, the Supreme Court finally pronounced its judgment in the petitions challenging the communication blockade in Kashmir which was in place since August 5, 2019 after the special status of Jammu and Kashmir was withdrawn. The matter was decided through the case of Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India where the two main petitioners were the executive director of Kashmir Times, Anuradha Bhasin and senior congress leader Ghulam Nabi Azad.

The three judge bench lead by Justice NV Ramana, R Subhash Reddy and B.R. Gavai engaged with some extremely important questions of law and laid down certain guidelines to be followed in future. Some of these included the validity of the prohibition of the internet by the government, the validity of the restrictions imposed by the government under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPc), the effect of such restrictions on the freedom of press and the question of whether the right to access the internet can be called a fundamental right.

On The Issue Of Internet Shutdown

The petitioners through the case challenged the notification of the government through which all modes of communication such as the internet, mobile and telecommunication were suspended. In this respect, the court ruled that the indefinite suspension of internet in Kashmir without specifying any particular duration is a violation of the Telecom Rules. the Bench cited various precedents and stated that,

“Complete broad suspension of telecom services, be it the internet or otherwise, being a drastic measure, must be considered by the state only if necessary and unavoidable. In furtherance of the same, the state must assess the existence of an alternate less intrusive remedy. The suspension rules have certain gaps, which are required to be considered by the legislature. One of the gaps relates to the usage of the word ‘temporary’ in the title of the suspension rules. Despite the above, there is no indication of the maximum duration for which a suspension order can be in operation. Keeping in mind the requirements of proportionality expounded in the earlier section of the judgment, an order suspending the aforesaid services indefinitely is impermissible. It is necessary to lay down some procedural safeguard till the deficiency is cured by the legislature to ensure that the exercise of power under the Suspension Rules is not disproportionate.“

The petitioners through the case challenged the notification of the government through which all modes of communication such as the internet, mobile and telecommunication were suspended.

On The Issue Of Section 144

With respect to the orders by the government restricting movement under Section 144 of the CrPc, the court held that the power under the section cannot be used to curb legitimate expression of democratic rights. It was further stated that Section 144 is a remedial and preventive measure which must be subject to proportionality. Moreover, with regards to this issue, the Court directed the government to publish future orders passed under Section 144 and also directed for these orders to be reviewed by the concerned authorities within seven days and for the future orders to be reviewed in a timely manner.

On The Issue Of Rights

The most important declaration made by the Supreme Court in the case was that the freedom of speech and expression as well as the freedom of trade and commerce through the medium of internet are the rights covered by the Constitution under Article 19(1)(a) and Article 19(1)(g) respectively.

Based on the precedents Odyssey Communications Pvt. Ltd. v Lokvidayan Sanghatana (1988), Secretary, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India etc., the court observed that, “Expression through the internet has gained contemporary relevance and is one of the major means of information diffusion. Therefore, the freedom of speech and expression through the medium of internet is an integral part of Article 19(1)(a) of the and accordingly, any restriction on the same must be in accordance with Article 19 (2) of the Constitution.” Moreover, the Court also held that the freedom of trade and commerce through the medium of internet is also constitutionally protected under Article 19(1)(g), subject to the restrictions provided under Article 19 (6).

However, the bench was reluctant to declare the right to access the internet itself as a part of the freedom of expression, despite stating that the right to carry on any trade or business under Article 19(1)(g), using the medium of internet is constitutionally protected. In order to justify the said reasoning, the court stated that, “None of the counsels have argued for declaring the right to access the internet as a fundamental right.“

A Vague Sense Of Comfort?

The Supreme Court dealt with some of the important questions of law and set guidelines for future, but it did not follow its own deductions. Nothing has been decided with respect to the the legality of the restriction orders that have been passed since the special status of Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the constitution was removed and the internet services suspended. Most of the people in the valley have been deprived of the access to internet which has lead to a massive loss in business, especially the IT industry and other activities dependent on the internet. However, the court has not declared the 158 day communication shutdown as unconstitutional and neither has it directed the government to restore all telecom services in Kashmir.

The Supreme Court dealt with some of the important questions of law and set guidelines for future, but it did not follow its own deductions. Nothing has been decided with respect to the the legality of the restriction orders that have been passed since the special status of Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the constitution was removed and the internet services suspended.

Moreover, as all fundamental rights have certain reasonable restrictions, in the present case, the court was to decide what would constitute a reasonable restriction on trade and communication through the means of internet. For this, the court referred to the Telegraph Act which governs the rules restricting communications. The court also relied upon the concept of proportionality, according to which, a measure should be proportionate to its object. When applied to the case of internet shutdown, it would mean that internet shutdown can be ordered only on the occurrence of “public emergency” or “in the interests of public safety.”

Also read: Kashmir: Why Women In Conflict Is A Category Of Intersectionality?

In light of the present case, the court was expected to review the orders passed by the government and establish whether they were proportional in nature. However, the bench failed to do so despite the fact that the government did not establish that its orders were proportional to the object of maintaining peace, something that the judgment requires as a prerequisite.

With respect to the Section 144 orders passed in Jammu and Kashmir, the court did not question its legality and instead, asked the government to review them. Additionally, in this case, the bench appears to have rejected Bhasin’s contention that the internet blockade had a “chilling effect” on the freedom of press. She specifically stated in the writ petition that she was not able to publish her newspaper from August 6 to October 11, 2019 , yet no evidence was put forth to that effect. However, the expression “chilling effect” suggests that individuals who suffer it are unlikely to leave any evidence of having suffered it because they would refrain from taking any risk that would invite the wrath of the government. Thus, the argument could not be rejected solely because there was no evidence to support it.

Now, looking into the practical implementation of the judgment, on January 14, 2020, the Jammu and Kashmir administration issued a three-page order to “partially” restore internet facilities in the Kashmir Valley and mobile connectivity in five districts of Jammu region. The order also stated that there will be complete restriction of such social media applications that may facilitate “peer to peer communication.” In concurrence with the judgment of the Supreme Court, the order stated that the reason for doing so is to is to prevent the transmission of fake news and targeted messages being spread by various separatists and anti – national elements allegedly operating in Jammu and Kashmir.

Also read: Kashmir: Why Women In Conflict Is A Category Of Intersectionality?

Therefore, despite being a step in the right direction, the judgment leaves one pondering whether it will finally end a democracy’s longest ever internet shutdown, or is it a vague comfort embedded with certain ambiguities.

Featured Image Source: Tech Crunch

About the author(s)

Learning and unlearning in an endeavour to smash patriarchy through my imperfect feminism.