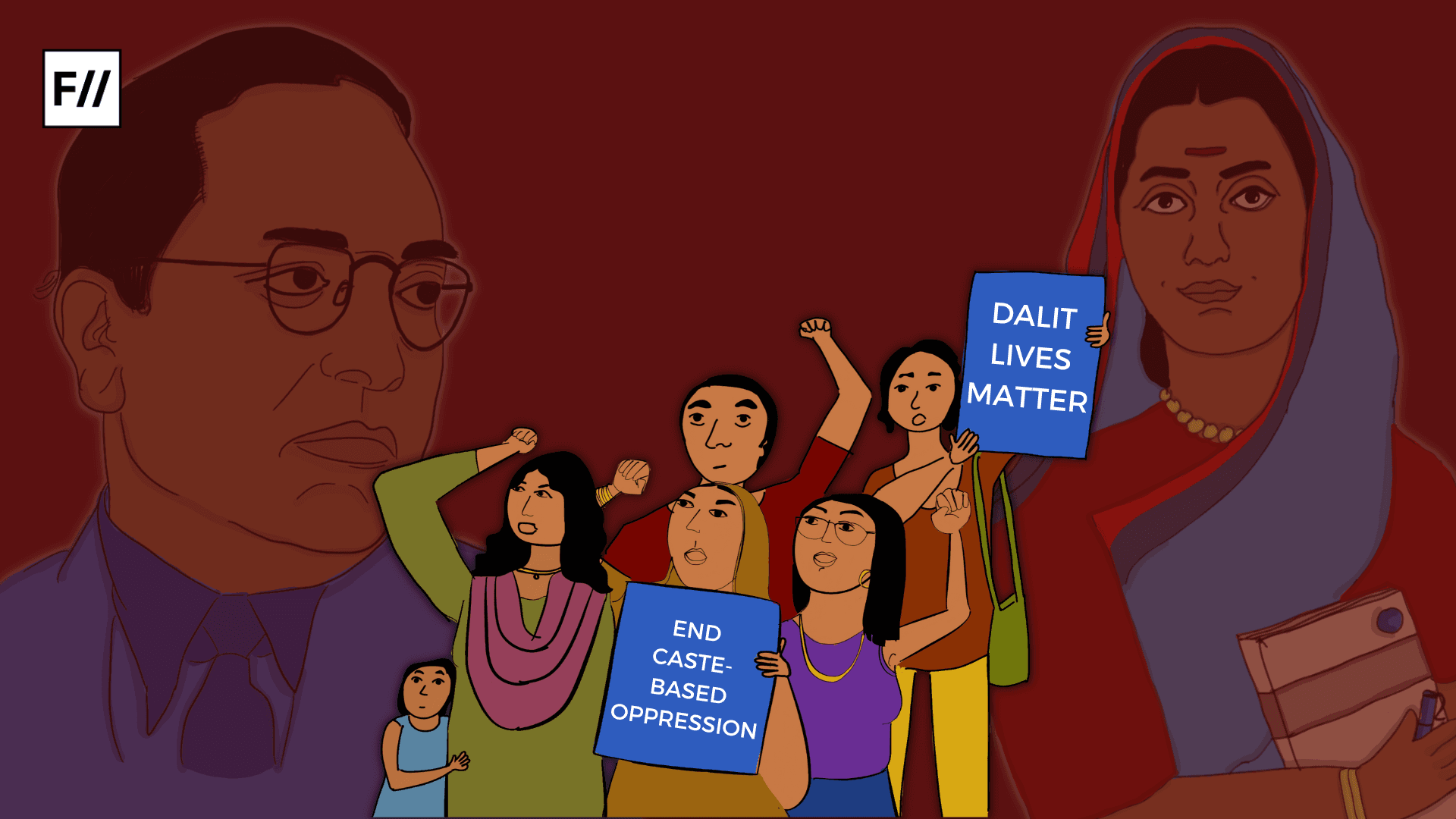

Editor’s Note: This month, that is April 2020, FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth is Dalit History, where we invite various articles about historical moments in Dalit movements as well as Dalits in history who have been part of the anti-caste movement in India.. If you’d like to share your write ups, email us at pragya@feminisminindia.com.

Siddalingaiah is one of the first Dalit Kannada poet, playwright, activist, and politician. He is an Ambedkarite and one of the founders of the Dalit Sangharsh Samiti (DSS), an organisation formed to fight for Dalit causes. In 1988, he became a member of the Karnataka Legislative Assembly and, in 2006, chairman of the Kannada Development Authority, a post with Cabinet rank. He has been head of the Department of Kannada at Bangalore University and a member of the University Syndicate of Kannada University, Hampi.

Literary Background

Siddalingaiah is a part of the Bhandaya or Dalit Bhandaya movement in Kannada literature, which began as a reaction and to the Dalit Movement in Karnataka. He’s the first Dalit poet to receive Karnataka’s highest literary award, “Pampa Award” in February 2020. His poetry was filled with fire and anger from the hardship he faced, and his call to fight atrocities took the form of poetry. Late critic D.R. Nagaraj said about Siddalingiah, “I trembled in surprise when I read my friend Siddalingiah’s poetry. The reason being the difference between the poet’s persona and his poetry… But his poems, they were fireballs. So this humility was just a facade, I learnt very soon. Behind this veneer of politeness was his mischievousness…”

He’s the first Dalit poet to receive Karnataka’s highest literary award, “Pampa Award” in February 2020. His poetry was filled with fire and anger from the hardship he faced, and his call to fight atrocities took the form of poetry.

His prose, unlike poetry, was humorous, mischievous, and full of youthful excitement and vigour. His autobiography, “Ooru Kare” in Kannada, and translated into English as “A word with you world” are both testimonies to his humorous writing. In an interview on the Hindu, he talks about humour being an intricate part of being Dalit. “During the Peshwas rule, the lower castes went around with brooms tucked into their backsides, and a pot for spittle hung around their necks. When this wretched system refused to look at them as fellow human beings, you know what they said? “When we spit, it rains pearls. And when we walk lotuses bloom. So we spit into our pots so that others do not make away with the pearls, and we sweep clear our footsteps so that others do not trample upon the lotuses!” Look how they created counter myths. If it was not their sense of humour, what was it?”

Also read: Why Ambedkar Matters To The Women’s Rights Movement

Anti-caste Struggle

DSS was part of the anti-caste struggle, and a means to unite the people of Karnataka to fight the structural castist oppression. DSS over the years broke down into factions, and when Siddalingaiah was asked how he sees it today, he said, “It is no longer a pressure group that can make the establishment take note of it. It lacks mature leadership. I wish that all the splinters group would come together and fight for a common cause. Sadly, there is very low ideological awareness. But that is the state of all progressive movements – be it the farmer’s, the labourers, the Left… all of it.”

As a member of the Legislative Council, Siddalingaiah was able to address and table many Dalit issues. Talking about other Dalits in politics and leadership roles, he said, “Most Dalit leaders, MLA or MLC, have not been able to raise Dalit issues because they fear they will lose in the next elections. Since most of the deciding votes are by the upper classes, a Dalit leader hardly speaks for his brethren. Many of the Dalit leaders would come to me and say, ‘There is this problem in our constituency, can you please raise it?’ This is exactly why Ambedkar in the 1932 Round Table Conference said that Dalit leaders have to be elected by Dalits itself. Now since non-Dalit electorate decides the fate of Dalit contestants, a true Dalit leader will not emerge. This is exactly why Ambedkar lost the elections twice!”

In 1988, he became a member of the Karnataka Legislative Assembly and, in 2006, chairman of the Kannada Development Authority, a post with Cabinet rank. He has been head of the Department of Kannada at Bangalore University and a member of the University Syndicate of Kannada University, Hampi.

For whom, and where, did the freedom of ’47 come?

It came to the pockets of the Tatas and Birlas

It came to the mouths which eat up people

It came to the rooms of the crorepatis

The freedom of ’47, the freedom of ’47

It did not come to the houses of the poor

It did not bring the ray of light

It did not lessen the sea of misery

It did not let bloom the flower of equality

This poem was written by Siddalingaiah over forty (40) years ago and translated roughly on the news minute.

Also read: Student Politics And Ambedkar: Voicing Dalit Bahujan Agency In University Spaces

Siddalingaiah believes the poems apply to the nation today more than it did forty (40) years ago, “I think it is more relevant than it was when I wrote it 40 years ago… Economic inequalities have increased, the poor live miserably, farmers are committing suicides. Liberalization, privatisation, and globalisation (LPG) are the enemies of people. But the worst hit are Dalits. With privatization, Dalits have lost out on affirmative action, which is not applicable in the private sector. We still need to ask people this question: For whom, and where has the freedom of 1947 come?”

Featured Image Source: Outlook India

About the author(s)

A freelance photographer & writer who drinks too much coffee.