When we think of a party at home, we imagine a fun-filled evening with guests and conversations. For our mothers, however, a party is not a time for relaxation. Its chaos. The short film Juice, directed by Neeraj Ghaywan, whose best known work include Masaan and Sacred Games, covers the very common and ‘normal’ scenario of a middle-class house party in an Indian household and highlights one very significantly internalized topic in our lives— gender roles.

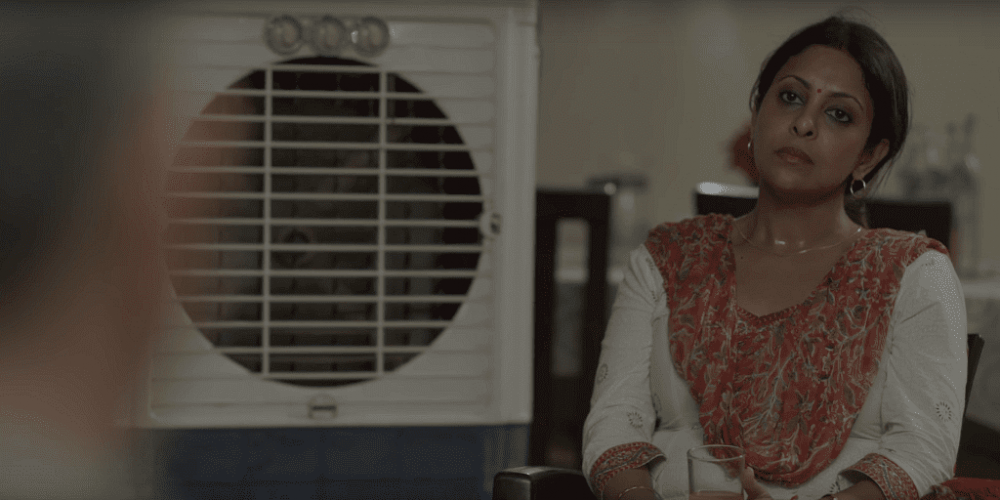

Juice begins with a setup that every middle-class Indian has witnessed in their own houses. It shows a housewife Manju Singh, played by the remarkable Shefali Shah, cleaning the half-eaten chicken bones of her husband and his friends from the table before moving on to watering the cooler to ensure the guests remain comfortable. The husband played by Manish Chaudhari, meanwhile, is regaling his friends with a story about his ‘incompetent’ female boss who had asked him to send an unnecessary email.

In the get-together, the men and women are separated on arrival with the men sitting together in the living room eating snacks and chatting about topics that they have very little knowledge about while the women are huddled in the heat-filled kitchen contributing to the cooking. Their roles as ‘guests’ versus ‘domestic caretakers’ are therefore immediately identified. Juice shows a stark difference between the two areas in the same house— “hot” versus “cool”, “comfort” versus “discomfort”, “party” versus “duty” and finally “relaxed” versus “chaotic”; the only common factor linking them being internalized patriarchy.

“Aap ko email se problem hai ya female se,” was the humorous reply from his friend before they all burst out laughing in front of Manju (with a “Don’t mind haan bhabhi”, of course). Thus, begins a story whose simultaneous subtlety and non-subtlety creates an ever-lasting impression on the mind of the viewers.

In the get-together, the men and women are separated on arrival with the men sitting together in the living room eating snacks and chatting about topics that they have very little knowledge about while the women are huddled in the heat-filled kitchen contributing to the cooking. Their roles as ‘guests’ versus ‘domestic caretakers’ are therefore immediately identified. Juice shows a stark difference between the two areas in the same house— “hot” versus “cool”, “comfort” versus “discomfort”, “party” versus “duty” and finally “relaxed” versus “chaotic”; the only common factor linking them being internalized patriarchy.

Photo Courtesy: Youtube

While the men are openly sexist, as seen in their discussion regarding the US elections and why Hillary (whom they refer to as “Bill Clinton’s wife”) will lose to Trump implying the inability of women to handle leadership positions, we simultaneously have women in the kitchen propagating other gender stereotypes. Having internalised their gender roles as ‘good’ wives/mothers, they passionately argue with one of their friends about how becoming a mother is a role that every woman must undertake despite her own plans and aspirations—a conversation which Manju steadily ignores as she continues her cooking.

Later when Manju is used as an example for their pregnant friend, as the ideal woman who quit her job after giving birth and took on the role of primary caretaker of the household and child, she retorts by saying, “Ye kaunsi kitab me likha hai ki ya to bachon ko paalo ya naukri karo, dono ek sath nahi kar sakte kya”. Therefore, in the same party and in the same household, the conversation of a woman is seen to be starkly different from a man.

Shefali Shah does not explicitly speak a lot during the film, preferring instead to do most of her acting through her eyes and expressions. “Diaper badalna hai toh woh hami ko karna padega na? Logon ke haath se toh remote chhoot jayenge,” is probably the only instance where her dialogue openly snarks at the opposite gender. She notices with a disapproving glance the imposition of gender roles when one of the women tells her young daughter to stop playing video games and go serve her brothers dinner, realizing then how these roles and ‘duties’ are defined right from childhood.

Also read: From Catsuits To Captains – The Evolution Of Women In ‘Superhero’ Films

Every time there is a task to be done—whether it is to stop the children from creating a ruckus in the living room or serving dinner for the men—Manju is immediately beckoned while her husband continues drinking with his friends. There is a hard hitting scene where the women are drinking tea and choose to serve the maid in a steel glass as opposed to the ceramic ones they’re using. While Manju glares at her friend knowing it’s wrong, she still does not protest the act thereby showing how even women have conformed to the societal hierarchy (gender, caste and class) which keeps them above at a higher pedestal than the maid.

Every time there is a task to be done—whether it is to stop the children from creating a ruckus in the living room or serving dinner for the men—Manju is immediately beckoned while her husband continues drinking with his friends. There is a hard hitting scene where the women are drinking tea and choose to serve the maid in a steel glass as opposed to the ceramic ones they’re using. While Manju glares at her friend knowing it’s wrong, she still does not protest the act thereby showing how even women have conformed to the societal hierarchy (gender, caste and class) which keeps them above at a higher pedestal than the maid.

Juice masterfully weaves the story of Manju Singh who goes on from kindly accepting her role to slowly getting more and more frustrated as the heat in the kitchen (and the anger in her mind) increases, complemented by her noticing the multiple impositions of gender roles around her to her finally reaching a boiling point and snapping. Her ‘rebellion’ is anything but explosive and loud. Her simple act of taking out the glass of juice and dragging a chair to sit in the front of the cooler (and the men) is seen as groundbreaking and yet this is the moment that has the most impact.

Manju’s eyes fill with relief at the cold juice that has finally given her some comfort in this hot and chaotic evening. Her act, simple enough as it is, is enough to make the men go silent and avert their eyes while the other women stand flabbergasted by the entrance (still not crossing into the living room themselves). Her ‘rebellion’ does not need words and the chastising eyes that Manju turns on her husband are enough to drive home the point.

Juice portrays a scenario that is familiar to us right from our childhood and yet something that has been internalized by us to the point of ignoring it. The mother plays the role of the host, cook, caretaker, cleaner and crisis manager whereas the father simply plays the host and occasional bartender while enjoying the party with the guests.

Also read: A Confession Of Corrections To Guru Dutt

The relevance of the story accentuated by the skillful directing makes it hard to miss the point and contemplate gender roles in our own households. The transformation of Manju does not come at the cost of a demanding ‘rebellion’ but in the quiet stand of identifying and taking charge of her own actions and decisions. The short film tries to highlight the gender roles that exist within our households and how the road to changing it does not need to be filled with loud protest but simple silences as hard and piercing as Manju’s final glare.

Feature Image Source: The Quint

About the author(s)

Vaishnavi Singh is an alumnus of The Young India Fellowship at Ashoka University. She is deeply interested in exploring the less understood aspects of something as vast and ever-changing as feminism. Vaishnavi is an opinionated introvert who loves travelling, watching movies and reading everything that she disagrees with.