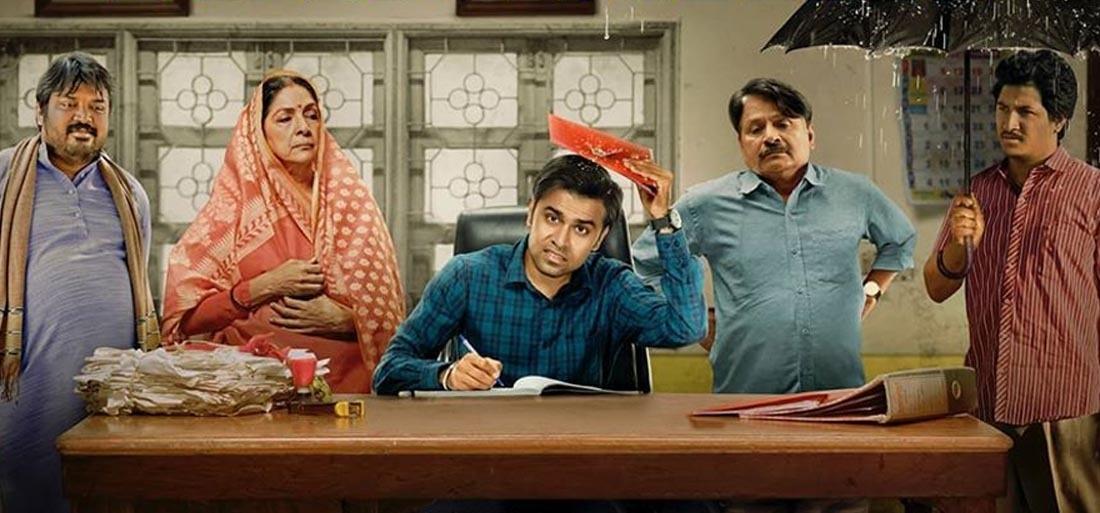

Panchayat’s heart is at the right place – or let’s just say at a real place. And the real makes it right, because the series has been uncompromising in its treatment of the plot line – as aggressive as ‘uncompromising’ might sound, the good-natured grey characters lend a breezy feel to the series. That is what Panchayat stands for – good-natured grey characters and their beliefs, but with the perpetual possibility of the grey fading into shades of white because a virtue is being constantly established by the writers about the central figures, almost as an apology on behalf of the characters themselves – they are ready to evolve, reluctant at first, albeit slowly, but they are ready to make amends to their problematic belief systems, and this is precisely why many like me are ready to give the benefit of doubt to the entire team.

Panchayat beautifully exposes its characters – it deconstructs every character in the course of its own narrative, a practice that would ideally be taken up by serious viewers. It creates a premise of flawed characters, and with the male characters outnumbering the females, we see a group of male characters falling flat on their faces and getting up to fix themselves, without the plot line glorifying any of their attempts. And that is precisely what has captured my attention – the character sketches of the male characters, their purposefully flawed nature and their overwhelming failures. Now, more than ever, we need characterisations such as these, as most popular culture characterisations of male characters are replete with a very obvious sense of heightened masculinity which would only make them party to a ridiculous number of success stories.

Let us start from the very end of Panchayat’s story line. You would expect Jitendra Kumar’s, Abhishek Tripathi to succeed in his attempt of cracking the all-important CAT examination—the writers had created a build-up for this sub plot, Abhishek’s ticket out of Phulera would be an excellent CAT score. And well, our very own ‘Mohan Bhargava’ fails and how.

‘Panchayat‘ beautifully exposes its characters – it deconstructs every character in the course of its own narrative, a practice that would ideally be taken up by serious viewers. It creates a premise of flawed characters, and with the male characters outnumbering the females, we see a group of male characters falling flat on their faces and getting up to fix themselves, without the plot line glorifying any of their attempts. And that is precisely what has captured my attention – the character sketches of the male characters, their purposefully flawed nature and their overwhelming failures.

Next, the fight sequence, which proved to be nothing short of a wild goose chase for both parties, was the epitome of attacking the otherwise machismo portrayed by popular culture. The writers constructed the setting, complete with guns, sunglasses, leather jackets and motorbikes – you would expect a very obvious Rohit Shetty-isque culmination. But the gun was never fired, the jackets were adorned to protect their bodies from an anticipated bout of thrashing, the bikes never participated in physics defying stunt; instead Abhishek’s own bike resulted in his own injury. The construction of this scene hinges on being a caricature – but this caricature is much needed; it is perhaps a direct attack on the ridiculousness of the Rohit Shetty genre.

Same stands for Raghubir Yadav’s Prandhanpati spending 3 nights at a supposedly haunted locality, and although the script only spent about a minute on Prahlad and the Pradhanpati’s antiques while they spent nights under a haunted tree, it was amply clear that their otherwise masculine bravado was not enough to ward off the non-existent ghost. Generally, the ‘social reform’ that is brought about by Abhishek Tripathi’s appointment as the Secretary of Phulera’s Panchayat office is often de-glamourized, de-glorified by Abhishek himself – with his resentment towards living in Phulera and generally giving up an urban lifestyle. Abhishek does initiate noteworthy projects in the village, but he constantly establishes that he does not want to be Swades’s ‘Mohan Bhargava’ in the first place—he does not want to be the hero who saves the day—he simply desires a high-flying job, very banal, very everyday, very anti-climactic.

It might seem like through my reading of Panchayat, I gained pleasure in pointing fingers and laughing at the failures, an almost ‘it was bound to happen to men’ moment. However, the pleasure was gained through realising that the men in the series have been stripped off their gender’s toxic history or at least an attempt was made – the men of Panchayat were indeed lesser ‘men’. We deserve more men in anti-climactic situations, an overwhelming number of heroes in climactic situations have stood as alibis for men in our everyday realities – somehow, the on screen heroes flexing their muscles were a good example for the men in our lives to flex their generational privileges. This machismo presented both off and on screen is a carefully constructed one, with the sedimentation of multiple populist portrayals of men.

It might seem like through my reading of Panchayat, I gained pleasure in pointing fingers and laughing at the failures, an almost ‘it was bound to happen to men’ moment. However, the pleasure was gained through realising that the men in the series have been stripped off their gender’s toxic history or at least an attempt was made – the men of Panchayat were indeed lesser ‘men’. We deserve more men in anti-climactic situations, an overwhelming number of heroes in climactic situations have stood as alibis for men in our everyday realities – somehow, the on screen heroes flexing their muscles were a good example for the men in our lives to flex their generational privileges.

The indispensability of Vikas and Prahlad in the entire series is also important to our discussion—for Abhishek and the Pradhanpati respectively, both these characters are central to their daily professional and personal functioning. It is also amply established that there is a substantial class-caste difference between the central characters and their apparent sidekicks. However, in too many sticky situations, Vikas proves to be Abhishek’s mouthpiece while the Pradhanpati almost always seeks Prahlad’s advice and is also fairly dominated both by his towering physicality and his scathing remarks.

In quiet ways, Vikas and Prahlad show their ‘seniors’ their places, in the process letting the audience know that both Abhishek and Pradhanpati’s lives would pause without their presence. This is an important development, as across the series we see both Abhishek and the Pradhanpati explicitly making casteist statements – be it Abhishek’s issue with Vikas’ pronunciations or the Pradhanpati’s perpetual obsession with ensuring an endogamous marriage for his daughter. Thus, the writers’ investment in constructing Vikas and Prahlad’s indispensability is a quiet triumph for both these characters—it is established that Abhishek and the Pradhanpati’s upper class-caste privilege would fall flat on its face without Vikas and Prahlad hoisting it up.

Also read: Kabir Singh: The Poster Boy For Toxic Masculinity

However, Panchayat does engage in two particularly tired tropes – firstly, the quintessential ‘angry wife’ trope and secondly, an incorporation of a heightened sense of nationalism at the very end.

The second plot development presents some potential however, I believe it is an unintended by-product of the script. Neena Gupta’s Manju Devi being unfamiliar with the national anthem of her country exposes multiple systemic problems. Other than the obvious exclusion of women in bureaucratic positions, it also brings home the realisation that the national anthem is not an accessible nationalistic icon. The obvious expectation of being familiar and subsequently having the national anthem memorised is a product of a social placement—intersections of your identity would ensure your accessibility to nationalistic cultural icons.

It really does not come off as a shock given Manju Devi’s rural placement, in addition to the exclusion her gender has faced historically with respect to having access to information. This plot development perhaps acts as an attack upon the strictures placed by a government to maintain a consistent image of the nation – it brings forth questions of whether the ideas of a ‘nation’ is solely defined by political boundaries, is it not a product of the imagination triggered by one’s layered identity? If nationalistic icons such as the national anthem has failed to permeate through every nook and cranny of the country’s landscape, is it successful in propagating an all-encompassing uniform image of the nation?

In quiet ways, Vikas and Prahlad show their ‘seniors’ their places, in the process letting the audience know that both Abhishek and Pradhanpati’s lives would pause without their presence. This is an important development, as across the series we see both Abhishek and the Pradhanpati explicitly making casteist statements – be it Abhishek’s issue with Vikas’ pronunciations or the Pradhanpati’s perpetual obsession with ensuring an endogamous marriage for his daughter. Thus, the writers’ investment in constructing Vikas and Prahlad’s indispensability is a quiet triumph for both these characters—it is established that Abhishek and the Pradhanpati’s upper class-caste privilege would fall flat on its face without Vikas and Prahlad hoisting it up.

The ‘angry wife-frightened husband’ trope is a misfit in the script which otherwise attempts to quietly expose the male characters—it is historically a much abused development which feeds directly into the hands of the popular stereotypes pertaining to a ‘radical, angry female’, her anger of course unjustified. While most of Manju Devi’s concerns and suggestions are well-meant and rational, we see the Pradhanpati continuously establishing an unfounded sense of fright on his part – this perfectly fits into the traditions of populist portrayals of opinionated women, who are carefully constructed as threats to a very fragile sense of masculinity.

Also read: Why We Need To Reject Toxic Masculinity For Better Mental Health

Lastly, Panchayat is a TVF production – the same TVF which had harboured a sexual assaulter for many, many years. Although Arunabh Kumar has stepped down ever since the allegations against him came to light, stories like Panchayat is perhaps a slight compensation on their part, perhaps the beginnings of an undoing of a very, very toxic culture which also found place in many of their other works. Panchayat is a flawed, unformed beginning, but it surely is an encouraging start.

Sayati is currently in her final year of Master’s in Sociology at Presidency University, Kolkata. Her primary areas of interest are Culture Studies and Contemporary Kinship Studies. You can find her on Instagram.

Featured Image Source: Cinema Gators