Editor’s Note: This month, that is July 2020, FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth is Feminism And Body Image, where we invite various articles about the diverse range of experiences which we often confront, with respect to our bodies in private or public spaces, or both. If you’d like to share your article, email us at pragya@feminisminindia.com.

Posted by Vatya Raina

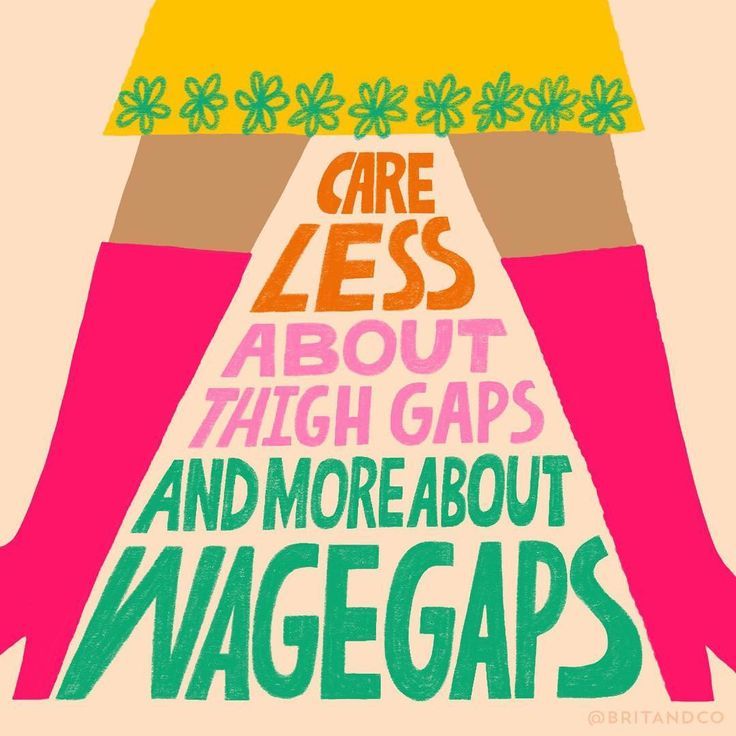

A thigh gap, for the people unfamiliar with it, is a cavity between the inner thighs when standing upright with both feet touching each other. The trend started in 2012 when visuals of models with the thigh gap from Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show exploded the internet introducing us to the ‘Thigh Gap’.

The media as an industry acts within the patriarchal structures of society, interacting with women’s bodies and teaching us what it means to be a female, and concurrently how to be a female, based on our sex assigned at birth which is fallaciously used as a model to gender bodies. The thigh gap trend came in as yet another teaching to self-discipline ourselves and conform to the societal pressures. This new aspiration led young women towards obsessive dieting and eating disorders.

Thigh gap was the new ‘Thinspiration’ (an amalgamation of thin and inspiration), and continues to be one of the most trending manias that shape our understanding of an ‘ideal body image’. It is the most trending objective marker of beauty. The internet is flooded with ‘ways to lose weight’ videos that have successfully lured women and young girls into aspiring for and achieving something as redundant as a thigh gap. When we go online, we have a galore of videos and articles promising us that perfect thigh gap in just a matter of days.

Thigh gap was the new ‘Thinspiration’ (an amalgamation of thin and inspiration), and continues to be one of the most trending manias that shape our understanding of an ‘ideal body image’. It is the most trending objective marker of beauty. The internet is flooded with ‘ways to lose weight’ videos that have successfully lured women and young girls into aspiring for and achieving something as redundant as a thigh gap. When we go online, we have a galore of videos and articles promising us that perfect thigh gap in just a matter of days.

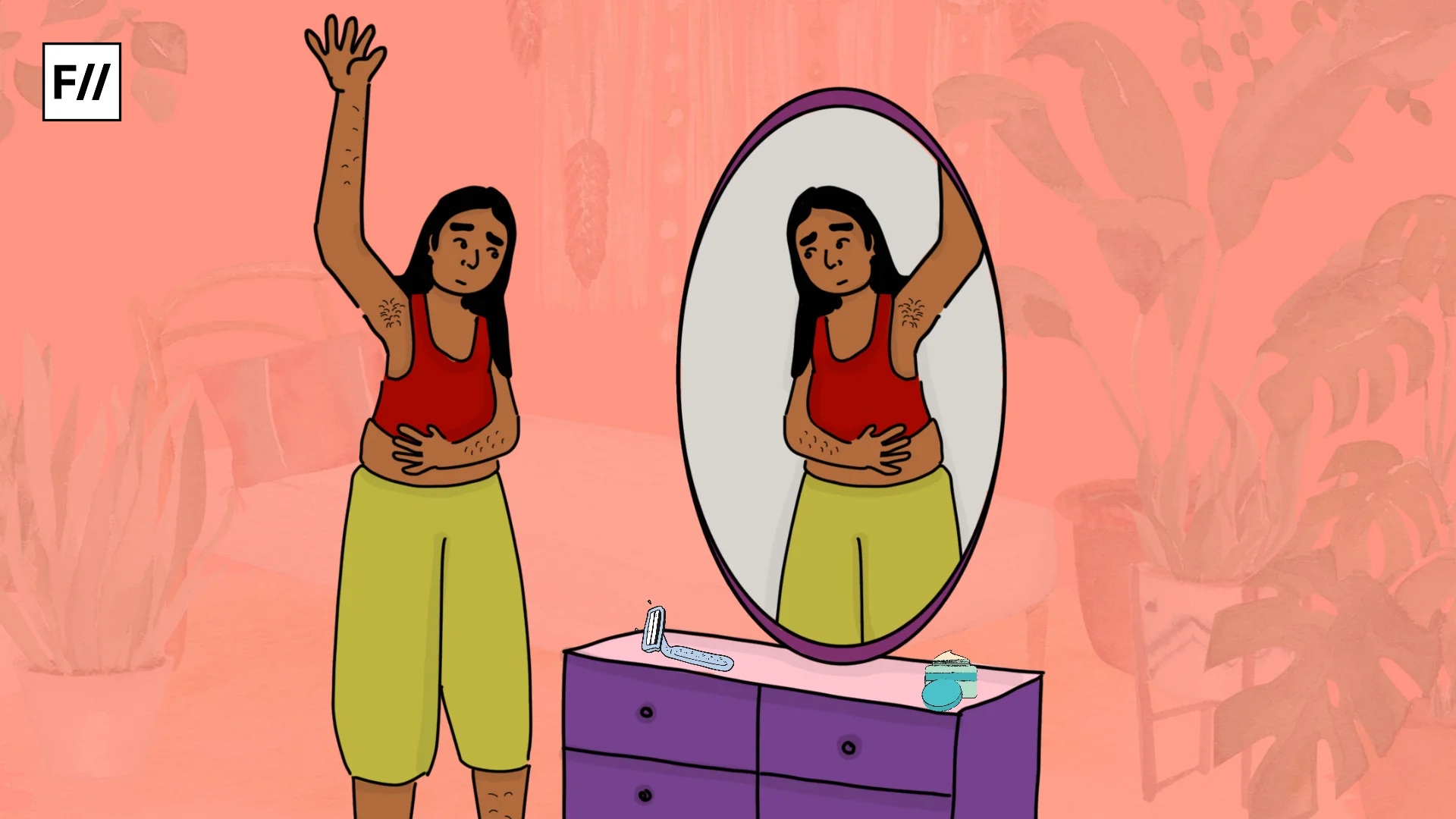

The exhausting idea of “feminine beauty” is defined within the limits of patriarchy. Visual online culture backed by the capitalist beauty and fitness industry magnifies this notion of feminine beauty. The recurring pressure of self-discipline, to perfect our bodies, to keep our “unwanted” hair away, and to make our fats burn, is a ploy to compel us to ‘fit in’ to the standard ideals of beauty. Many of us who are unable to build our defense, spend our time shrinking and hiding. Our bodies become our liabilities, which have to be presented and portrayed according to the expectations of society.

Historically, women’s bodies have been situated within the binaries of divine and whore: The divine wife and mother who pleasures her husband and bears his children and the whore, who becomes the vamp, the homewrecker, the loose woman. These images sanctioned and legitimized in the media put forth the definition of the ideal woman as ‘sexy, but not sexual’. We grow up internalizing that society has the right to determine our character.

Also read: “It Leaves A Scar”—The Psychological Burden Of Marks On Our Bodies

Our generation is known for its “selfie culture”. It means that we see and learn from the images that are reflected on us. We are taught to judge ourselves and our bodies very easily and when we are unable to meet the set standards, we end up disappointed and in a state of self-loathing. It can also lead to fatal illnesses. Social media has been no alien to Generation Z. From our bodies to our opinions, everything is shaped by the internet these days. This gap remains a part of the larger trend of ‘thinspiration’. On failing to achieve this wrongly glorified and romanticised body image, we experience an increase in body dissatisfaction which leads to decreased self-esteem.

A direct response to the thigh gap trend is the mermaid thigh movement. The movement has “called out” the body-shaming trend of thigh gap and promoted a body-positive image of being beautiful without the thigh gap as well. It has encouraged women to be comfortable and confident in any and every body type. The growing conversation around mermaid thighs has not only pushed the boundaries of an ideal body image but also motivated people to be confident in their bodies.

A direct response to the thigh gap trend is the mermaid thigh movement. The movement has “called out” the body-shaming trend of thigh gap and promoted a body-positive image of being beautiful without the thigh gap as well. It has encouraged women to be comfortable and confident in any and every body type. The growing conversation around mermaid thighs has not only pushed the boundaries of an ideal body image but also motivated people to be confident in their bodies.

However, I am still unable to overlook the existence of the commodified and sexualised nature of this trend. The sexual nature of this trend signifies ‘sexual access’ to women’s intimate parts. In addition to the control of women’s fashion by the male-dominated society, our bodies are also inaccurately controlled by the structure.

As a young girl, when I started obsessing over the ongoing fashion trends like off-shoulder shirts, I was sat down and told by my father that, “…the various cuts in women’s clothing, (example: cold shoulder tops or cleavage openings) are controlled by this patriarchal structure (like everything else), it is to attract attention to and sexualize that specific body part and it is how this structure will always try to trap and obsess you with your appearance, so you do not raise questions and function under their control.”

Now, I understand that any piece of clothing one wears is one’s choice, but the 15-year-old girl learnt her lesson of how the structure functions as well as controls our choices and opinions. Fashion remains the favourite child of capitalism. Our choice is also constrained by the patriarchal values incorporated by capitalism. Therefore, the importance of the gap between our thighs is another way to achieve the unconsented sexualisation of women’s bodies.

Also read: The Real-Time Effects Of Reel-Time Representation

We have always been told how our bodies can be our assets and our brains are of no good. This shifts our attention to the importance of reclaiming our autonomy and self-worth from a world which is going to staunchly bring us down and judge us based on how we should look. A thigh gap should be nothing more than something which can be achieved when one stands with their legs apart. The debate is not about, ‘to have’ or ‘not to have’ a thigh gap but about creating a platform for all body shapes, sizes, colours and abilities.

Vatya Raina, is a student of Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, pursuing her Master’s in Women’s Studies. She completed her Bachelor’s in Spanish language and literature from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. Find her on Instagram and Facebook.

Featured Image Source: Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Vatya is a Master’s student of Women’s Studies at Tata Institute of Social Sciences. She has played an active part in student politics with her organisation, AISA (All India Students Association) and continues to be a part of it. Her view of the future is intersectional and she believes in change. The love for theatre keeps her alive. She fears silence the most.