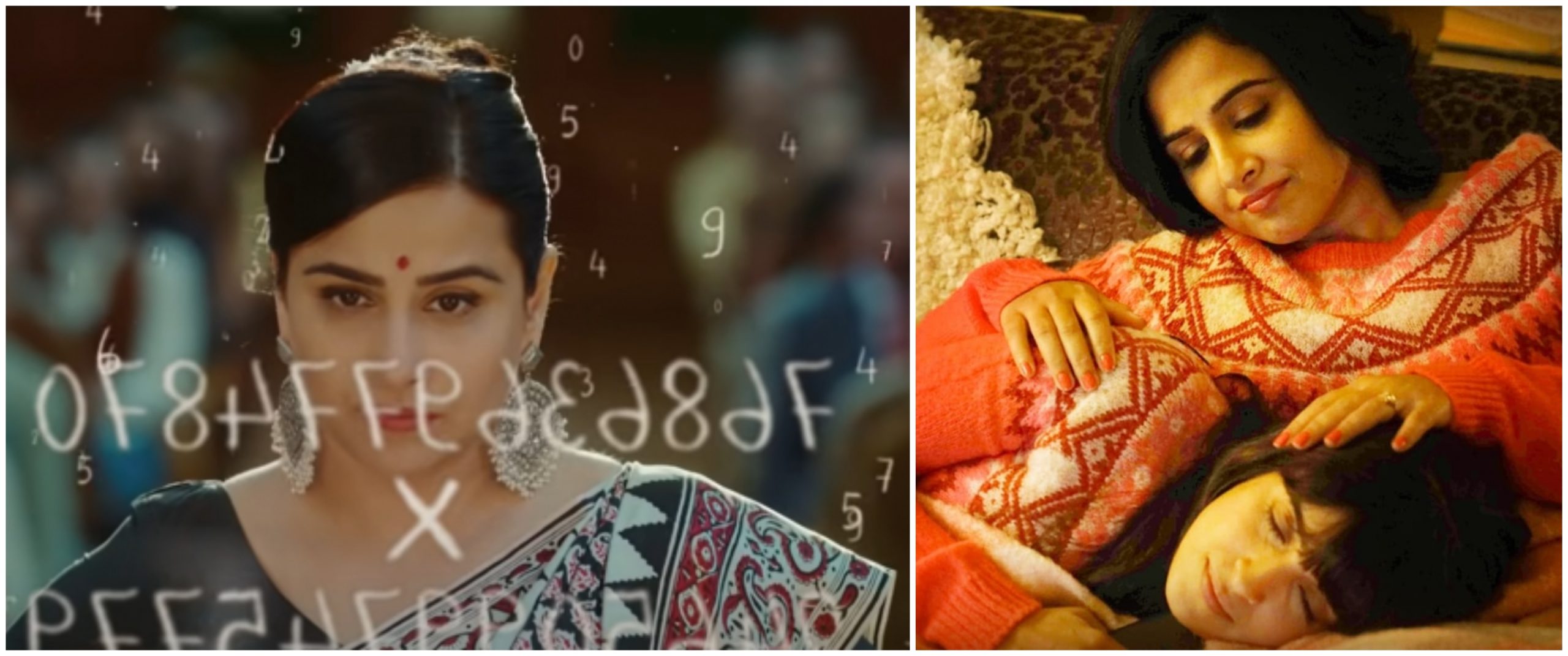

The moment of vulnerability that pushes Shakuntala Devi (played by Vidya Balan) to question her inseparable love for Mathematics is a scene where her husband (played by Jisshu Sengupta) mentions on the phone that their daughter uttered her first word, “Baba”(father). The scene belongs to Anu Menon’s biopic of the internationally acclaimed Indian mathematician Shakuntala Devi, which recently premiered on Amazon Prime.

Shakuntala is on an international tour in the scene and her infant is back home in Calcutta under the care of her husband. She tears up, ends the call on the pretext of poor connectivity and flies back home. What follows is a heated argument between the couple as Shakuntala proposes taking her husband and child along on work tours so as to not miss out on her personal life. Despite being a Guinness Record holding mathematics genius, who the world refers to as a human computer, Shakuntala is seen to have second thoughts about her career because she is asphyxiated by what psychologists would call ‘the mother’s guilt’.

Mother’s guilt or the guilty mother syndrome is an emotional state of feeling persistently ineffective as a mother. The mother believes that she is not doing enough for the child and experiences extreme guilt when she spends time away from the child for work, self-care or other reasons. These feelings primarily arise when the mother feels that she is failing to deliver what is expected of her as a good mother.

Mother’s guilt or the guilty mother syndrome is an emotional state of feeling persistently ineffective as a mother. The mother believes that she is not doing enough for the child and experiences extreme guilt when she spends time away from the child for work, self-care or other reasons. These feelings primarily arise when the mother feels that she is failing to deliver what is expected of her as a good mother.

In the scenario mentioned above with respect to the film, Shakuntala Devi feels extremely guilty despite being aware of the fact that her child is in the loving care of the father, an equally responsible caregiver in parenting. When she suggests that both her husband and daughter travel with her, he is quick to object because he does not want to be her “stepney husband”. Though it is fair for a man to not want to globe trot with his wife, the following question raised by Shakuntala is poignant – “If you (her husband) were a world-famous mathematician, the entire world would expect me to pack my bags and tour with you so that you do not miss out on your personal life. So why is it different because I’m a woman?”

This question forms the fundamental conflict of the film. It is also central to the lives of many working mothers who struggle to balance work and family without compromising on identity. The eventual, unavoidable choice that plagues most working women at some point in their lives is – career or family? It is undeniably true that an extra emotional burden is thrust upon women when it comes to raising children. The fact that the film indulges in Shakuntala Devi’s domestic conflicts more than it does in her extra ordinary intellect is very telling of the skewed vision with which we look at women and motherhood. That even the film maker, a woman herself seems to be unable to steer the story into a broader horizon, only confirms how ingrained this bias is in our collective psyche.

Does a woman have to play in to our expectations of a “good mother” to be appreciated for her success?

The moral burden of being a “good mother”

The society mandates that a “good mother” is one who makes herself available round the clock, with selfless vigil and energy to cater to the child. In circumstances when she has to be away, she must bend over backwards to make sure her absence is not felt. This constant image to live up to, puts the mother under immense duress. Many young mothers opt not to work because of this fear of failure on the home front.

What happens in the process is that instead of looking at motherhood as one of the many roles in a woman’s life, it is placed at a pedestal that supersedes everything else she is, or aspires to be. It is of course every woman’s choice to embrace motherhood the way she deems appropriate, but pressurizing her and limiting her individuality to motherhood alone is the denial of her rightful choice to be the kind of mother and person she wants or does not want to be.

The “good mother” is a carefully constructed set of patriarchal commandments put in place to make sure women are held more accountable for the upbringing of children and the smooth functioning of the family. Working mothers guilt themselves into unnecessary self-criticism about their commitment towards children because they are conditioned to believe that somehow, they are the ones who have to be more available. The busy father who misses a sports day match at his child’s school is allowed to be absent because he has important work, work that brings money to the table.

The “good mother” is a carefully constructed set of patriarchal commandments put in place to make sure women are held more accountable for the upbringing of children and the smooth functioning of the family. Working mothers guilt themselves into unnecessary self-criticism about their commitment towards children because they are conditioned to believe that somehow, they are the ones who have to be more available.

But replace him with a working mother who pitches in equal or more financial contribution towards the family in the same scenario, and we get what we call “the career woman with no time for her child.” She must feel guilty because she is not good enough for the society to be a respectable mother. In her book, Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead, author and Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, Sheryl Sandberg writes,

“When a couple announces that they are having a baby, everyone says ‘Congratulations!’ to the man and ‘Congratulations! What are you planning on doing about work?’ to the woman. The broadly held assumption is that raising their child is her responsibility.”

Mother’s guilt as is evident, is an outcome of the gendered assumption that a mother is duty-bound to do more because we have set motherly love on a divine footing and it now works as patriarchy’s best trope to ensure that women feel guilty about going back to work or spending time for themselves after childbirth. Men often do not experience guilt in similar, daunting ways. Slacking at childcare is not a cause of stress for them as much as it is for women because they are used to having women in their households who step down from other pursuits to ensure wholesome childcare.

This is not to ridicule the efforts of the many fathers who pitch in to childcare, but to remind ourselves that it is not a father’s magnanimity to have been there for his child because childcare is a joint responsibility to be shared collaboratively by both partners. There is no space for blame in it, neither is it fair to expect mothers to be guilty and fathers to be patted on the back when they make time to cater to their offspring, despite their schedules. In her Wellesley Commencement Speech 2015, Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said,

“…and in media interviews make sure fathers are asked how they balance family and work. In this age of ‘parenting as guilt,’ please spread the guilt equally. Make fathers feel as bad as mothers. Make fathers share in the glory of guilt.”

Also read: Women’s Sexuality In The Indian Nationalist Discourse

What brings down the thematic focus of Anu Menon’s film is the sad fact that she also seems to give in to the larger than life idea of maternal love in the narrative of a film that strives to document the incomparable genius of a defiant woman who earned global repute in the 1950s against several odds. Shakunatala Devi had a mind that worked in ways the world could not fathom. Her love for numbers was also her love for clarity, precision and her dismissal of bias. She simplified mathematics for students without any formal education in the subject. She published books on mathematics, astrology and homosexuality.

Her book, “The World Of Homosexuals” is considered to be the first study on the subject conducted in India. She also contested the Lok Sabha elections in 1980, against Indira Gandhi. While documenting such a feisty, multi-faceted personality, it is disappointing that the film chose not to indulge in the mysterious, meditative preoccupation her intellect had with numbers as much as it did with her role as a mother. Her tryst with patriarchy including the racist instances where her South-Indian, saree-clad, pig tail spotting appearance was considered a joke by white men are not treated with the emphasis or nuance they deserve in the film.

Domestic conflicts are of course a seminal part of a person’s life. But when we look at biopics made on men, it can be observed that the importance and relevance of their intellect triumphs the narrative of their inner lives. There is a heroism about those films that accentuates the body of the subject’s work and celebrates the brightness of their minds. In Shakuntala Devi’s biopic, apart from the scenes that showcase Devi on stage shows, basking in the glory of applause and accepting felicitations for her brilliance, there is no engagement with the guiding conscience of her choices as a globe-trotting mathematician who herself asks, “Why be normal when I can be amazing?”

Also read: Shankuntala Devi: The Math Prodigy Who Researched About Homosexuality | #IndianWomenInHistory

In the end, the film narrows down her ambitious dynamism into the guilt of a conflicted mother who sometimes regrets having been passionate about her career. Towards climax, the film voices the importance of looking at mothers as independent women with minds of their own, but the dialogues seem performative since the film itself fails to stick to them in its treatment of Shakuntala Devi’s story.

The film gives in to the very same cliché, overdone motherhood trope that it tries to warn us against. This is quite a disservice to the rich, extraordinary life of Shakuntala Devi, a phenomenon in herself. For all her glory and daring, I wish the film celebrated the prodigy that Shakuntala Devi was, instead of melodramatising her into a guilty mother seeking approval from her child for being amazing instead of normal.

About the author(s)

Sukanya is a lawyer-turned-journalist with experience in writing, editing, development communication, and advertising. She holds a graduation in law, a post-graduation in philosophy, and a post-graduate diploma in print journalism. She is also a published poet and was awarded the All India Poetry Prize in 2015. Her journalistic work is deeply focused on gender and intersectionalities, and they appear in Feminism In India, True Copy Think, and The News Minute.

This is really well written thought provoking article.

My sentiments exactly!! Great piece- her daughter did not do justice to her remarkable mother. No mother is perfect or “normal.” It saddens me that the line “why be normal when I can be amazing?” held such a negative connotation and the focus of the biopic, at the end of the day, was on Devi’s inability to adhere to societal expectations of a “good” mother rather than a successful woman!

While your articles makes some good points on what is perceived as acceptable for a woman/ mother, you forgot that at the end of the day, this movie is a biopic, a true story where the director hasn’t taken creative liberties as clearly mentioned by the Shakuntala Devi’s daughter. How the protagonist behaved in the situation is how she actually felt. The director could have changed the story to potray that the protagonist didn’t feel that way but then it wouldn’t be true or fair to her. She made mistakes and learnt from them ( When I say mistakes, I mean the one she made trying to separate her daughter from her father, tried to push her into staying with her, not neglecting the child. I believe while the child had an eventual childhood and missed certain stuff in life, she still lead a entitled childhood, a good one, certainly better than most kids get anyway.)That was supposed to the message in the end.