TW: Mentions sexual violence and victim blaming and related trauma

Lacy M. Johnson in her memoir The Other Side writes,

“I’m afraid the story isn’t finished happening. Sometimes I think there is no entirely true story I could tell. Because there are some things I just don’t know, and other things I just can’t say. Which is not a failure of memory but of language.”

We are rarely trained to respond appropriately to “disclosures of sexual violence” and so, when someone close or distant confides in us about their experience of sexual abuse we are either at a loss of words of comfort or too quick to extend our solidarity where we end up blaming the survivor or making statements which might bring more pain to them.

We are rarely trained to respond appropriately to “disclosures of sexual violence” and so, when someone close or distant confides in us about their experience of sexual abuse we are either at a loss of words of comfort or too quick to extend our solidarity where we end up blaming the survivor or making statements which might bring more pain to them.

Here is a list of things that you should definitely not say to a survivor of sexual assault.

1.“It has happened to most of us, it’s not extraordinary”

In a world where sexual violence against women and other marginalised genders is prevalent to the extent of its normalisation, people tend to trivialise the experiences of a survivor if it fails to arouse shock or pity.

A cis-het man professor passing lewd comments during viva, incidents of groping in religious and other public spaces, for instance has sadly become a part of our everydayness and so when someone gets visibly disturbed by such incidents one tends to cite their own experience of a similar violence to make the other person feel better. But it does exactly the opposite—to tell our experience of sexual assault to another survivor has the potential of creating a sense of comfort but to police their reaction to it ends up invisiblising their trauma; it also is a form of subtle victim blaming where one questions the seriousness of their experience.

2. “But why don’t you take legal actions against the abuser?”

Who is unaware about how long legal trials take to even start in any cases of sexual violence and more so when the survivor comes from a social location which lies lower in the social ladder power?

And if trials begin, they require the survivor to revisit the trauma and as they say ‘the process itself becomes a punishment’. Most if the workplaces or educational spaces which are required to have an internal committee to look into the matters of sexual harassment and assault are either confusing without one or rarely encourage their employees to report such incidents. From character assassination to facing attempts to murder (and actually being murdered) or to being jailed because of demanding her statement to be read by a social worker, survivors in Indian legal spaces (though not limited to) have rarely been comforted or delivered justice.

This dissatisfaction and disillusionment with legal institutions is one of the driving forces behind the global #Metoo movement.

Also read: No Indian Judges, Marriage Is Not The Remedy To Sexual Abuse

3. “You will never feel complete again.”

While trying to make case for justice after the 2012 Delhi rape and murder case, the then BJP MP Sushma Swaraj referred to the victim of the incident as a “zinda laash (comatose)”. She might have been trying to convey the gravity of the crime but her comment ended up stigmatising the victim. This is founded in the argument of ‘honor’ and ‘purity’ which in the general understanding is lost when a woman is sexually assaulted and what is not obvious to many is that by this ideological underpinnings we are reducing the entire existence of a survivor to their sexuality.

At times we fail to understand that solidarity not only means the acknowledgement of the trauma and pain of the survivor but also the respecting the right of the survivor to move on and lead a life which is not only about pain.

The patriarchal Indian conscience has a well constructed image of women who are at the receiving end of sexual violence—acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. At times, we fail to understand that solidarity not only means the acknowledgement of the trauma and pain of the survivor, but also the respecting the right of the survivor to move on and lead a life which is not only about pain.

4. “Are you sure that it happened because you don’t even remember the entire incident?”

James Hooper and David Lisak in an essay for Time argue that-

Fear, “can direct attention away from the horrible sensations of sexual assault by focusing attention on otherwise meaningless details. Either way, what gets attention tends to be fragmentary sensations, not the many different elements of the unfolding assault. And what gets attention is what is most likely to get encoded into memory.”

Disclosing any case of abuse especially sexual abuse is a very triggering process which leaves the survivor in an emotionally vulnerable space where support of those who have been narrated the incident becomes important. On top of that, questioning the survivors about the authenticity of their claim by demanding minute details or tangible evidences portrays the failure of the legal systems and the society at large, at understanding the psychology of abuse.

5. “Why did you wait so long to talk about it/ report it?”

I recently saw a video of popular poet Rahat Indori’s mushaira ( poetry recitation gathering) where he jokes about #MeToo movement in which women have started telling stories of sexual assault from past and that he is afraid of finding his name in the morning newspaper someday; his ‘joke’ is greeted by a thunderous applause (nobody is shocked here given the fact that mushairas are attended mainly by men for various reasons). This shows that most of us fail to recognise our adherence to a misogynistic thought process. .

Processing the reality of being sexually abused is complicated; one has to fight the internalised urge of self blaming; one also has to feel that the people on the other end will somehow be able to make sense of their pain. Then there are other reasons like abuser holding powerful positions or perhaps a lack of supportive environment or even a legal recognition of an assault. Survivors have all the rights to choose if/when and how to narrate their experience.

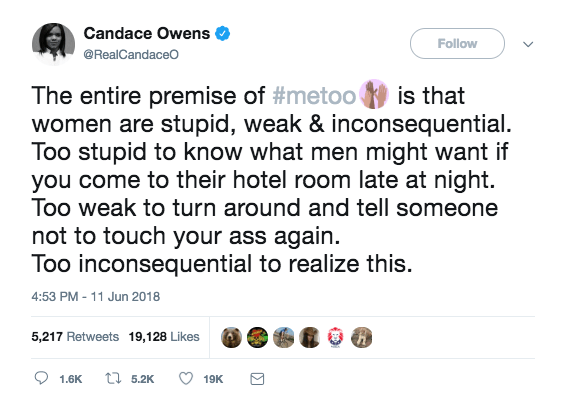

Also read : Victim Blaming In The Garb of Women Empowerment

6. “If you are a feminist then you must come out with your survival story in public.”

Incidents of sexual violence may be unique but they are never isolated. All these incidents irrespective of their gravity are results of this patriarchal society’s collective failure to create safe spaces for women; a failure to create masculinities that are not driven by fragile egos that try to reproduce their power by abusing women.

As feminists women might be able to get around with the shame that comes with an experience of sexual violence but to come out in public not just opens them to more hurt and unnecessary questioning, jeopardising their careers or relations but also to defamation cases—another law that abusers have weaponised in order to silence those who call them out.

7. “I thought you people were in a relationship!”

To say this or perhaps invoke the marital status of a survivor in order to dismiss their experience of abuse is deeply problematic. Intimate partner violence is more rampant than we choose to believe. Society teaches us to always associate sexual abuse with the figure of a ‘stranger’, an ‘unknown other’ probably to escape having uncomfortable discussions around consent, marital rape and abuse by relatives and close friends. Marital rape is still not recognized by Indian law because marriage is a “sacrament”(?).

No matter what kind of relationship people share or their past engagements (be it ten years or ten seconds ago) is not a license to do it again. Remember consent is always dynamic.

8. “We are with you, just be a little more careful next time”

As understanding and concerned friends, partners, parents, colleagues or therapists, telling a survivor to be ‘more careful’ so as to avoid being assaulted might pass as harmless or even concern but it implies a shift in the responsibility of the assault from the perpetrator to the survivor; that the latter could have saved herself if she had tried enough. Women have been assaulted by strangers and lovers, in broad-day light and in nights, in crowded as well as isolated places, while they were drunk also also when they were sober.

When we ask survivors to be “careful” we are basically asking them to not occupy as much space as they do- to deliberately belittle their existences.

First of all, what does being “too friendly” even mean? How is one supposed to quantify one’s friendliness towards someone? And if this is the line of reason we are to follow, then, how do we rationalize the action of perpetrators who were total strangers for the survivor?

9. “I am never ‘too friendly’ with my colleagues, just to be on the safe side.”

First of all, what does being “too friendly” even mean? How is one supposed to quantify one’s friendliness towards someone? And if this is the line of reason we are to follow, then, how do we rationalise the action of perpetrators who were total strangers for the survivor? It follows the same old defense of men that puts the blame on the survivor mostly a “woman for luring the man—for turning him into a monster” Cis-het boys and men are rarely taught about boundaries and often early incidents of abuse are pushed under the carpet by parents and very often teachers and later on by bosses.

This kind of social conditioning makes them entitled and rightly believe that they can get away with abusive behavior because accept it or not most of the socio-cultural odds favour them.

Also read: Infographic: Sexual Violence In Conflict

It is on those who are witness to these stories of violence to be not inflict more pain than already exists to the survivor and most importantly understand and even ask how would the survivor want us to respond.

Featured Image Source: Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Aparna is a post-grad student of Women's Studies at TISS, Hyderabad. When she is not talking about intersectional politics and re-reading The God of Small Things, she can be found listening to Mehdi Hassan while she pets cats and collects yellow flowers.