“Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.”

~Ways of Seeing, John Berger

Humour and satire have been instrumental in representing the many political realities we are currently living in. In this way, owing to its unique multiplicity in meanings and forms, political cartoons have provided us an almost democratic space to dissent. While most usually have a momentary impact on public opinion, in a few cases these messages echo longer and even strike up the public into action.

In the present political context, cartoons have also provided a safe space to communicate the otherwise provocative reality, which is often so unsettling that many choose to consume it in passivity. The sad reality of today’s India is that cartoons are amongst the only few safe spaces where one can communicate the truth. Many activists, writers, and journalists who speak out and provide ‘real’ visibility to the conditions are either arrested, killed, or simply censored. Recently, Masrat Zehra, a professional photojournalist from Kashmir was booked under the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) for allegedly indulging in “anti-national activities” on social media. All these hint at the growing intolerance that the ruling party has shown towards what can be understood as a breakthrough movement of storytelling as a means of resistance.

Past, Present and Future

Image Source: DNA

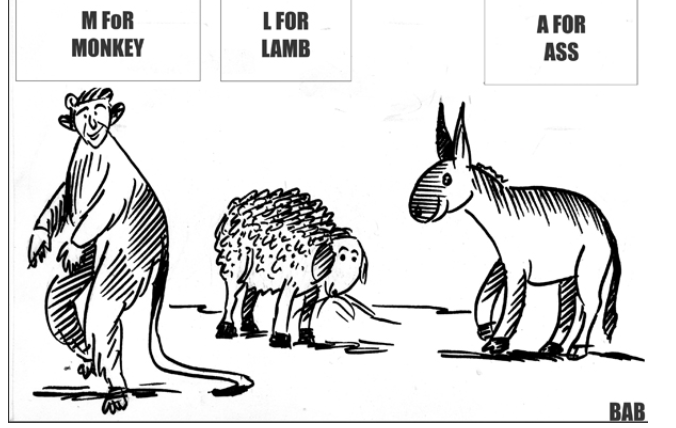

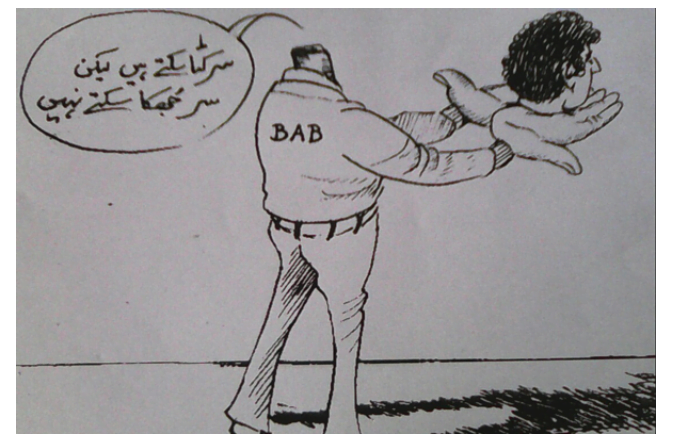

Kashmir’s political cartoon culture began sometime around the 1940s and focused on creating powerful imagery through collective memories to evoke feelings familiar to its viewers. For a long time, its rich cartoon culture was held synonymous to Bashir Ahmad Bashir’s (dearly called BAB) unapologetic, tongue-in-cheek cartoons that brilliantly brought humor out of the ordinary. Interestingly, BAB’s caricature of Sheikh Abdullah on the Srinagar Times is believed to be the first-ever cartoon in the history of Kashmiri journalism. His cartoons were also deeply instrumental in expressing the collective anger and suffering that Kashmiris have gone through in the past few decades. Though now in his old age, BAB continues to draw relentlessly and often shares his work on Facebook.

Image Source: DNA

The impact of his works in Kashmir was such that the readership of Srinagar Times increased many folds with many subscribing to it just to get a glimpse of BAB’s witty sense of humor. Many such cartoons are now archives of a rather distinctive trajectory of Kashmiri politics and have also turned into cultural icons over the years. In many of BABs interviews, he narrates anecdotes of getting into trouble for his work. One which particularly stands out is when his newspaper stirred controversy for a cartoon he drew when Jammu and Kashmir Assembly MLAs got into an ugly verbal spat. Following this, BAB appeared in front of the assembly and defended his cartoon on the grounds that he like many others was simply exercising his freedom of speech. However, part of the reason why he was able to do so was that he owned the newspaper he worked for. As things stand now, many cartoonists have transitioned into digital artwork and social media putting their work out for a larger viewership. Even though there has been considerable progress especially with contemporary Kashmiri cartoonists adopting diverse platforms like newspapers, digital magazines, and even comic strips to publish their work, most of them often bear the brunt of unspoken censorship.

Even though there has considerable progress especially with contemporary Kashmiri cartoonists adopting diverse platforms like newspapers, digital magazines, and even comic strips to publish their work, most of them often bear the brunt of unspoken censorship.

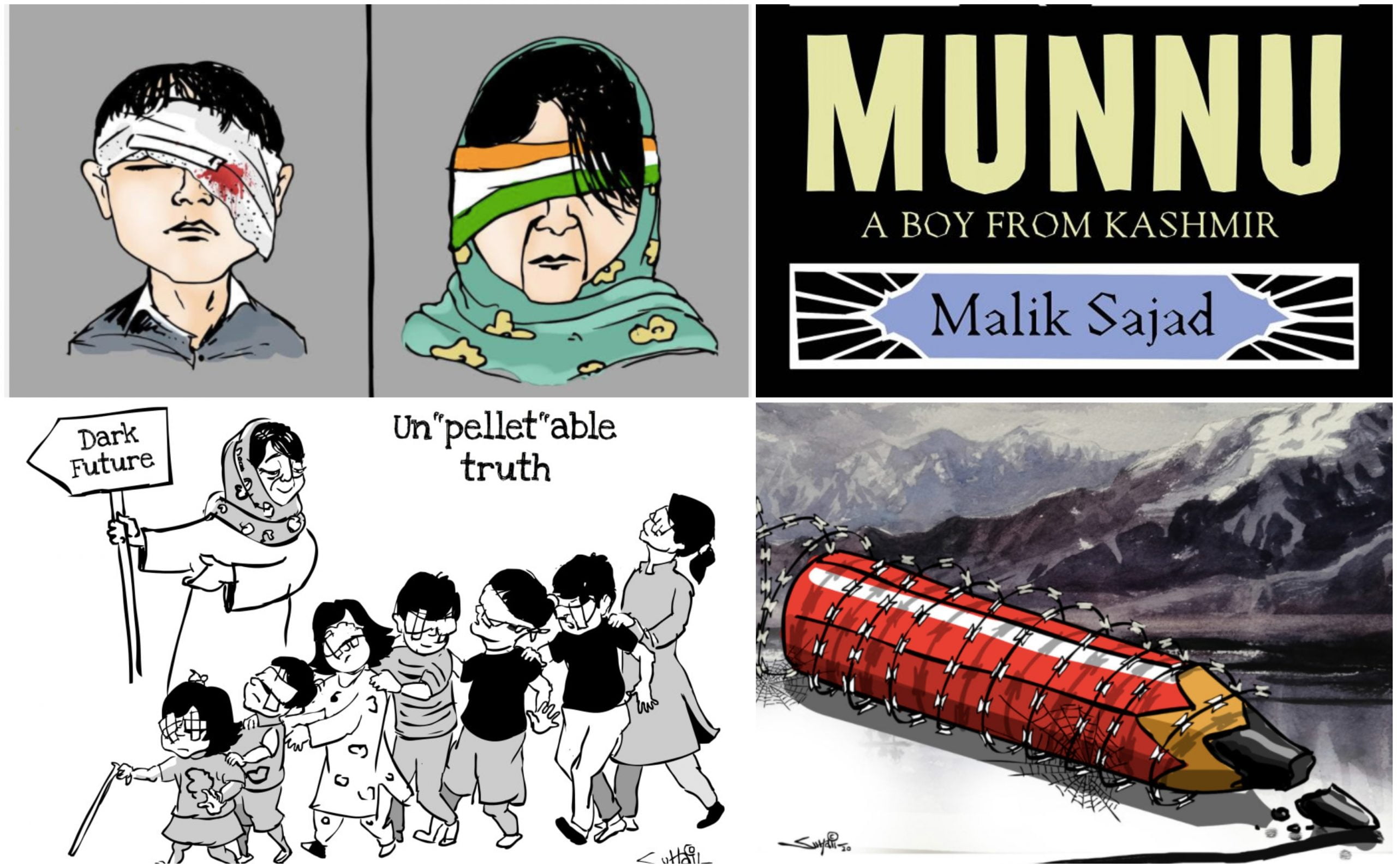

Newer progress in Kashmir’s political cartoon culture was seen when Malik Sajad, released a first of its kind graphic novel, Munnu: A Boy from Kashmir that traces the life of a seven-year-old boy navigating through the realities of living in a conflict zone. The book is a clever and satirical rendition of Art Spiegelman’s remarkable graphic novel Maus. In Sajad’s version mice (for Jews) and cats (for Germans) are replaced by the Hangul deer, an endangered species found in Kashmir (symbolic in some senses). Ultimately, the work is instrumental not just for the unconventional medium it adopts, but also the ease with which is amalgamates art and storytelling.

Also read: The Swelling Male Gaze Of Kerala’s Cartoon Culture

Representation And The Freedom Of Pens?

Cartoons may not be the whole truth but certainly, present a large part of reality wrapped in light humor. A deeper analysis of why cartoonists are pivotal to politics and media, in particular, trace back on how they represent realities. The striking representation and presence of guns, barbed wires, and violence as symbols of lived realities point towards something larger. As feminists, we need to understand that our ideas of representation stem from our unique experiences. In recent past, the representation of Kashmir in political cartoons has struck many controversies. BAB’s infamous cartoon on Sheikh Abdullah stirred up a huge controversy leading up to point where the cartoon was removed from NCERT textbooks and replaced with a rather pacificatory image of Kashmir during those times. It is safe to say that the small space on our front pages reserved for low-paid, censored cartoonists has signified the truth with greater sensitivity despite persistent arbitrary censorship.

Even though digital platforms have been a powerful medium for cartoonists to share their work, many of them have come under attack. Many cartoonists who have turned to social media, sharing their digital artwork, are often trolled for by people of diverse ideological alignments for their works if administrative censorship was not enough. A lesser-known side of digital platforms is the unsaid hush up that many social media sites like Facebook and Instagram impose with no explanation but often follow it with a vague message contending how the post goes “against community guidelines”. The question one needs to ask here is that if at all, we are living in a digital community, isn’t there a pressing need to re-examine how various identities we take up virtually can be limiting if one does not play an active role in shaping and reshaping them?

The growing influence of Kashmir’s cartoon culture has brought us to reflect that even though we have politicized news, we are yet to become political about a significant part of the news we consume. In terms of representation, women cartoonists remain almost absent from this scene.

In a letter for the Cartoonist Rights Network International, Suhail Naqshbandi, a cartoonist from Kashmir explains how cartoonists in Kashmir are being censored into silence. He also explains why he quit Greater Kashmir, a leading newspaper daily in Srinagar.

“The editor said he felt that cartoons had become passé the world over, and yet he still wanted them. Later I realized these mixed messages were a tactic for bargaining on remuneration. But freedom to create and express freely was curtailed; I was clearly told to avoid making cartoons of high-ranking ministers, military, police, and political friends of the newspaper’s management. This led to self-censorship and made my job tougher as I had to find other ways to transmit my message, using indirect satire through allusion and tropes.”

The letter also points towards the implicit hierarchy that exists within journalism wherein cartoonists lie somewhere between “a junior reporter and a stringer… Sadly this is the attitude of many journalists who don’t consider cartoonists their peers. In fact, cartoonists are pariahs of journalism in Kashmir. We are a rare breed of creative who have a nose for news and an artistic touch.”

The growing influence of Kashmir’s cartoon culture has brought us to reflect that even though we have politicised news, we are yet to become political about a significant part of the art we consume. In terms of representation, women cartoonists remain almost absent from this scene. This is not to say that the domain of art and resistance in Kashmir is entirely male-centric. Women are actively claiming agency drawing inspiration from their own lived experiences and excelling in all domains of artistic expertise. Often, the debates on representation pin down to where Kashmir women are visibly present resisting through individual art and expression. We need to look beyond this rhetoric because it often comes with presumptions and uninformed realities. In this way, it is imperative to be critical but also sensitive to the paths that marginalised communities adopt towards social change.

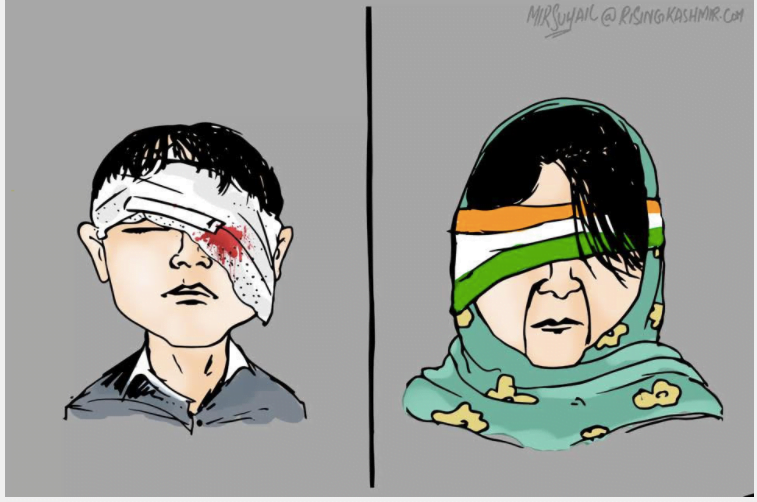

For many like Mir Suhail, cartoons have been “a way of educating people outside through visuals about the everyday realities of people here who are just asking for the freedom to live a life of dignity”.

Also read: The Cartoons Of Mario Miranda And The Art of Sexist Nostalgia

Featured Image Source: The Wire