Warning: Multiple spoilers

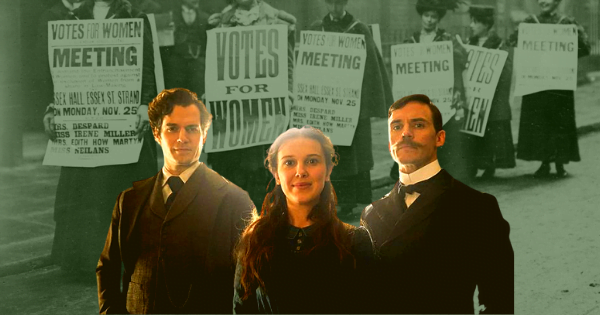

At the surface, as intimated by the trailer—Enola Holmes passes off as a whimsical, comedic adventure, with perhaps a hint of romance. Sounds about right—except that the movie has about 50 additional layers to it. Directed by Harry Bradbeer, written by Jack Thorne and based on the book series by Nancy Springer, Enola Holmes is the story of Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes’ teenage sister Enola (Millie Bobby Brown). After their mother, Eudoria (Helena Bonham Carter) mysteriously goes missing on Enola’s 16th birthday, the Holmes brothers are called in for the rescue. Unfortunately, for the sheer combined size of their male egos, they won’t be doing any rescuing at all.

Departure from Tradition

On a quick personal note—while I know that Enola Holmes has nothing to do with previous versions of Sherlock Holmes in pop culture, it’s impossible to completely isolate it from the vast field of canon by Arthur Conan Dyle and its multiple resurrections (good and bad) on celluloid. The last version of anything to do with the Holmes family that I saw was the BBC series starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman. With time, I grew to actively detest the series.

The episode ‘The Abominable Bride’ literally demonised the Suffragettes and even made them resemble the Ku Klux Klan. Towards the arc of the storyline—the women’s rights group stood silent with deadpan expressions while Sherlock mansplained their situation and their motivations—for the sake of ‘context’. In the episode titled ‘The Final Problem’, it was revealed that the Holmes family had another genius who was a woman. That joy was short-lived. The genius sister, Eurus Holmes, was a psychopath who inflicted immeasurable cruelty. Again for the sake of ‘context’, it was later revealed that she was desperate for her brother’s affections and her violent actions were rooted to the latter.

Enola Holmes brings back the Holmes sister and the Suffragette elements, and places both as central storylines and neither have anything to do with Sherlock’s affections or approval. They don’t really need him, for they are complete storylines on their own. Enola is brave, bright, vulnerable and absolutely endearing. The Suffragettes make it clear, time and again, the reasons for why their movement must exist and the actions they must undertake to ensure a new and better world for future generations. On a side note, I cannot express how relieved I am that ‘hysteria’ was not mentioned once.

Also read: The History Of ‘Hysteria’ And How Science Can Be Sexist

Meeting Enola (and wanting to be her friend)

From watching the trailer, we already know that this is not your conventional Victorian heroine. Enola is determined to take matters into her own hands. Courtesy of her convention-eschewing and firebrand mother Eudoria, she is proficient in literature, chess and combat—with a penchant for word games. On the surface, she is a textbook badass. Look a little deeper and you can spot her vast reservoir of empathy. While her upbringing was an attempt to shield her from the patriarchy and systematic inequalities of the external world—she always knew more than she let on. Another stereotype that was broken by Enola Holmes: you can be a brilliant detective and be a decent person at the same time. In this setting, genius sociopathic jerks are not welcome.

On the surface, she is a textbook badass. Look a little deeper and you can spot her vast reservoir of empathy.

She is street-smart, quick on her fists and feet and extremely efficient, as proven by her ability to quickly overcome the daunting and grimy landscape of 19th century London and its hostile elements. She meets the Viscount Tewkesbury (Louis Partridge) who looks the part of a ‘quintessential hero’—but is in constant danger and is in repeated need of rescuing. Where the latter is concerned, Enola rises to the occasion magnificently. However, their relationship dynamic does not comprise one party rescuing the other and the rescuee swooning in the arms of the rescuer. It’s a budding romance that entails the concept of ‘you scratch my back and I scratch yours’—except they do it happily and selflessly. They help and support each other, as well as pull each other out of tight spots.

The Insufferable Holmes Brothers (with some scope of redemption)

I must admit I jumped to conclusions and I was NOT happy about Henry Cavill being cast as Sherlock. Having immersed myself completely in all the Sherlock Holmes stories as a child, I had a very set notion of what Sherlock must look like (Robert Downey Jr came close to my very rigid demarcation). The latter was combined with my unfavourable opinion of Cavill’s acting skills.

Henry Cavill as Sherlock was a pleasant surprise. I did not deem it possible for a Sherlock who joked, showed compassion, felt remorse, got told to shut up and sit down and one who developed an affection for others. Cavill rose to the occasion. This is a Sherlock who gets called out for his white male privilege. This is a Sherlock who is outpaced by his younger sister. While he was open-minded and more accommodating of Enola, he was also calculating and emotionally distant and refused to acknowledge his faults as a physically and emotionally distant brother, and a son who looked the other way when his mother needed him most. But he evolves, becomes an occasional source of support for Enola and comes to term with the idea of a sister who would be a remarkable comrade and a worthy adversary.

The character of Mycroft Holmes (Sam Claflin) is an obnoxious toad. I am not joking when I say that his character needs a trigger warning at all times. Traditionalist, patriarchal, conservative and a control freak – Mycroft’s approach to Enola is one of ruling with an iron fist (much like the idea of a British state he desperately wants to hold onto). At first, he seems incapable of basic humanity having been so wrapped up in Victorian society’s ideas of appropriate and especially misogynist ideas about women’s roles in society.

According to him, his free-spirited, jujitsu-efficient and clever sister must dress properly, must have her spirit broken (he literally calls her ‘unbroken’) by a finishing school for privileged ladies and must be presentable in society in order to be married. Her aspirations don’t matter to him and he shows no remorse when destroying her agency. He later learns what a mistake it is to underestimate Enola.

The Storytelling Narrative

One of the storytelling and cinematic features of this film is that of a journey—and it does a good job of transporting the viewer from one place to another—and the journeys here are many. What really helps this aspect of storytelling is Enola consistently breaking the fourth wall and literally asking viewers for advice and inviting them to keep her company. While her name spelt backwards spells ‘alone’—her mother reminds her that she is never alone. Maybe that really is the purpose of Enola breaking the fourth wall. While the journey is solo, Enola is never actually alone. We the viewers are there with her through all of it—rooting for her through her triumphs, her obstacles, her tendency to literally headbutt dangerous elements as well as the occasionally terrible but well-meaning decisions.

I did not deem it possible for a Sherlock who joked, felt remorse, got told to shut up and one who developed an affection for others. Cavill rose to the occasion.

We are carried through Enola’s journey from the lively but isolated Ferndell Hall to the daunting and bustling interiors of London. We accompany Enola while she cycles through the countryside. We are front-seat spectators in her escapade-filled journey from childhood to adolescence. We watch as the Holmes brothers struggle to evolve when face to face with a sister who will defy all things convention. Credit to the cinematography and the pacing of the film where it’s due – it does justice to these multiple journeys and ensures that the audience is always aware as to how the characters reach their physical and emotional destinations.

There has been come criticism towards this film, describing it as ‘tepid’. While I respect their opinions, I would also like to point out that this film shouldered a LOT of tropes and narrative arcs and executed most, if not all, of them. Besides the A-Z plot, it undertook non-linear narratives, very layered and multi-dimensional characters, multiple genres, a lot of elements from Arthur Conan Doyle’s canon, important moments in England’s history and managed to be a love letter to word scrambles all at the same time. This story has a little bit of everything for everybody—some chilling scenes, some laughs, the whodunnit mystery element, historical fiction, feminist reclamations of space and last but in no way least—a love for the game of scrabble.

Also read: The Madwoman In The Attic: How “Mad” Was Bertha Mason In Jane Eyre?

Featured Image Source: Collider

About the author(s)

Friends with half the dogs in the city, can make a career out of procrastinating and when people engage in body shaming, am quick to remind them that I eat patriarchy for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Brilliantly written, thank you for articulating the experience of watching Enola Holmes so wonderfully; I had been looking for the right words!