Cilappatikaram (literally, “The Tale of an Anklet”) is a Tamil epic, a remarkable example of one of the earliest pieces of Sangam Poetry (poetry that talks of love), passed down through oral traditions. Often considered somewhat feminist, written by a Jain monk Ilango Adigal between first and third century AD, Cilappatikaram is an interesting piece of literature that makes a woman the lead of the story. More than that, she ends up defending her husband and “winning” him back in some ways. But how feminist can we call this story?

Cilappatikaram starts with the marriage of Kannaki, the “noble daughter of a prince among merchants” to Kovalan, an equally virtuous man. The ideals of virtue around this time, for a woman, had much to do with her “chastity”. Kannaki is portrayed as the prime “wife-material”, so to speak, literally mentioned in how “beyond all praise was Kannaki’s name renowned for making a home”. But as it so very often happens with the men in classical literature, Kovalan inevitably falls in love with Matavi, a courtesan, and “under her spell” abandons Kannaki. Courtesans around this time were one of the only women to be highly educated, skilled in arts and crafts traditionally reserved for men. The use of “under her spell” however, points to the relatively similar sentiments of the public itself. She is someone who is almost “witch-like”, someone who will “steal” away the man -by “bewitching” him.

Also read: Tamil Cinema And Its Misogyny Endorsing The Vain Macho-Hero Image

In ‘Cilappatikaram‘, Kannaki is the ideal wife. The translation would be that she has a subversive nature disguised in the form of “devotion”. Distraught, she remained “chaste and innocent”, loyal, and waited for her infidel of a husband to come back.

But, in Cilappatikaram, Kannaki is the ideal wife. The translation would be that she has a subversive nature disguised in the form of “devotion”. Distraught, she remained “chaste and innocent”, loyal, and waited for her infidel of a husband to come back. And Kovalan does indeed come back, but only because of a misunderstanding that drives him away from Matavi. At a festival dedicated to the god Indra, they both sing of lovers, and they both assume they mean someone else. The reason why Kovalan leaves her is important, it shows the almost hypocritical arrogant belief he had and not because of his sense of duty to Kannaki. Kannaki never gets the choice of being angry-her character must be “ideal” at all times. Embodied in her almost radical character, Matavi exerts her own agency. She keeps the memories but decides to not beg for his love.

Kovalan returns to Kannaki, who unsurprisingly forgives him. She even moves away with him to the city of Maturai because the people who know them are angry at Kovalan for what he has done (rightfully so). In dire need of money, Kannaki takes off her anklets and asks him to sell them. This is a noteworthy motif because the anklet was an auspicious symbol of their marriage. The anklet changes the course of the story. Because it resembles the Queen’s stolen anklet, Kovalan is dubbed a thief and killed for it. The King is unjust, he looks for a thief only to satisfy his “nagging” wife. The relationship married men and women share in Cilappatikaram is almost relatable. It distinctly reminds one of Whatsapp jokes of men (who benefit from patriarchy) complaining about their nagging wives and how they are a “slave” to them.

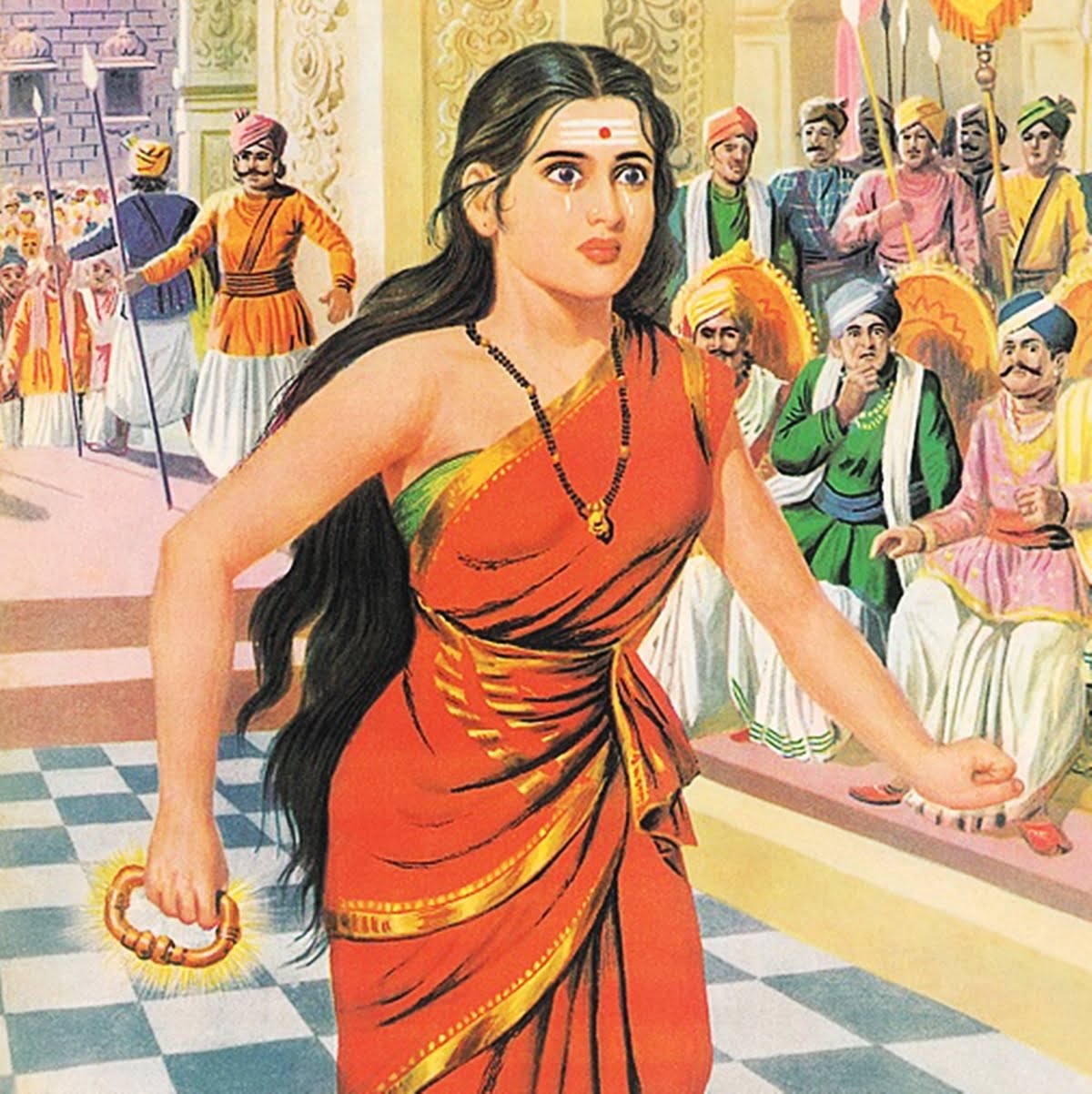

Back to the story, Kannaki finds out about his death when she goes to look for Kovalan; enraged, disheveled, resembling goddess Kali, she enters the palace and breaks her other anklet to reveal gems (the queen’s anklet has pearls) and immediately establishes her husband’s innocence. She then goes on a rampage tearing off her breasts and sets the city ablaze. The act itself becomes a symbol. Not only has she ended her marriage by breaking her second anklet and “saved” her husband(‘s reputation), she has ripped off her “feminine” features. The only people her fire spares are brahmins, good men, chaste women, cows, the young and the old. Surprise, surprise.

The gods take pity on her, she ascends to heaven on Indra’s chariot, is reunited with Kovalan, and becomes a goddess still worshipped today, Pattani. The rest of the story follows a King who uses her identity as an excuse to start wars.

Cilappatikaram uses symbolisms liberally, flowers defining “moods” of Sangam poetry amongst everything else. It is a reflection of the politics of the time as well. In fact, there is a bit about the unjust, unfair, corrupt royal family-the omens of their misfortune, however are not very sensitive in modern context: “hunchbacks, dwarfs, mutes and maidservants clustered thickly about the queen”. Right from the beginning, the politics of class lurks behind the curtains; the significance of Kannaki and Kovalan’s family being of a certain class and how it directly relates to them being virtuous is obvious.

But behind the façade of a woman “saving” her husband is an interesting dynamic of chastity as a weapon. The reason of the King’s death is an embodiment of this idea. He dies because he fails to protect “chaste and moral” woman, he does Kannaki wrong. It is not entirely because he is guilty of corruption and has ignored his duty to the kingdom-but because he cannot protect chastity either.

In Cilappatikaram, in her rant in front of the Queen, Kannaki mentions seven women and how they were all rewarded. A woman was told that a mound of sand on a river bank was her husband, so she didn’t move, and the river left the mound alone. Another woman was given back her husband when he was carried off by a river and she prayed to the gods-“embracing him, the golden vine of a girl returned home”. Another woman turned herself into a stone to avoid the gaze of onlookers to keep herself chaste for her husband- while waiting for him to come back from the sea (victim blaming, anyone?).

Yet another one told herself “Into a monkey face will I turn” because only her husband should look at her, a face she ripped off when he returned. Another woman dropped her child into a well because her husband’s mistress’s child fell in, then she rescued them both (because solidarity requires endangering your own child). Another girl heard her mother say “a woman’s understanding, however fine, is childish”, and for not listening to it, she gets punished by having her daughter marry her maid’s son (the idea of this being a punishment doesn’t quite sit well with modern readers). Besides pointing out that women can never fully comprehend something, that they fail to look beyond what’s in front of them, the fact that these women are all “chaste” does not skip the readers.

Chastity is also the major reason why Kannaki was rewarded. The eight women are not rewarded for their loyalty at heart, but the lengths they’d go to to protect the societal notions of an “ideal” wife. Kannaki is probably raised to the status of a god only because she was chaste. The story would have taken a completely different path if at any moment, Kannaki deviated from this ideal. Women are again hidden away, or told to hide away, they compromise and they put up with what’s given to them in marriage-going as far as to rip their own “monkey face” off so that no one lusts after them. And yet, this monkey face must be taken off in front of the husband, the face is not “ideal”.

In this sphere, the question that looms is-what becomes of women like Matavi in Cilappatikaram? She is smart and intelligent, and by no means a chaste woman. She grieves for Kovalan’s absence but she doesn’t get hung up on it. Not only is it important for the sake of the plot, it also makes her a mistress more than a courtesan.

In this sphere, the question that looms is-what becomes of women like Matavi in Cilappatikaram? She is smart and intelligent, and by no means a chaste woman. She grieves for Kovalan’s absence but she doesn’t get hung up on it. Not only is it important for the sake of the plot, it also makes her a mistress more than a courtesan. She isn’t as “equal”, she doesn’t get a say in what is given out to her either. And yet, even if she were to rip off her breasts, it’s not certain that she’d have become a goddess. So, she chooses a “silent resignation”.

Also read: How Tamil Cinema Normalises And Promotes Rape Culture

Kannaki on the other hand, ripped off her breast. This also makes the reader question if the results would have been the same without this action. In Cilappatikaram, her token of “femininity” is taken away, she is all the more fearsome when this happens. And yet again, we see that the woman is rewarded when she is chaste, when she chooses to throw away her femininity. She doesn’t need it anymore, it seems. Even though Kovalan is gone, she must remain loyal. Again, it brings us back to the beginning of Cilappatikaram. Only chastity is rewarded, none of the loyalty.

Featured Image Source: Jackson Cyril/Medium

About the author(s)

Anvi is a student of English literature who finds it condescending to divide literature into high and low, guiltlessly enjoys mangas, and uses her literary criticism skills to analyse them. She also likes to fight the patriarchy one at a time by hoping to spread more awareness about it.

This is so well put. Thanks for writing it da.

Love this article thank you Anvi !!!!