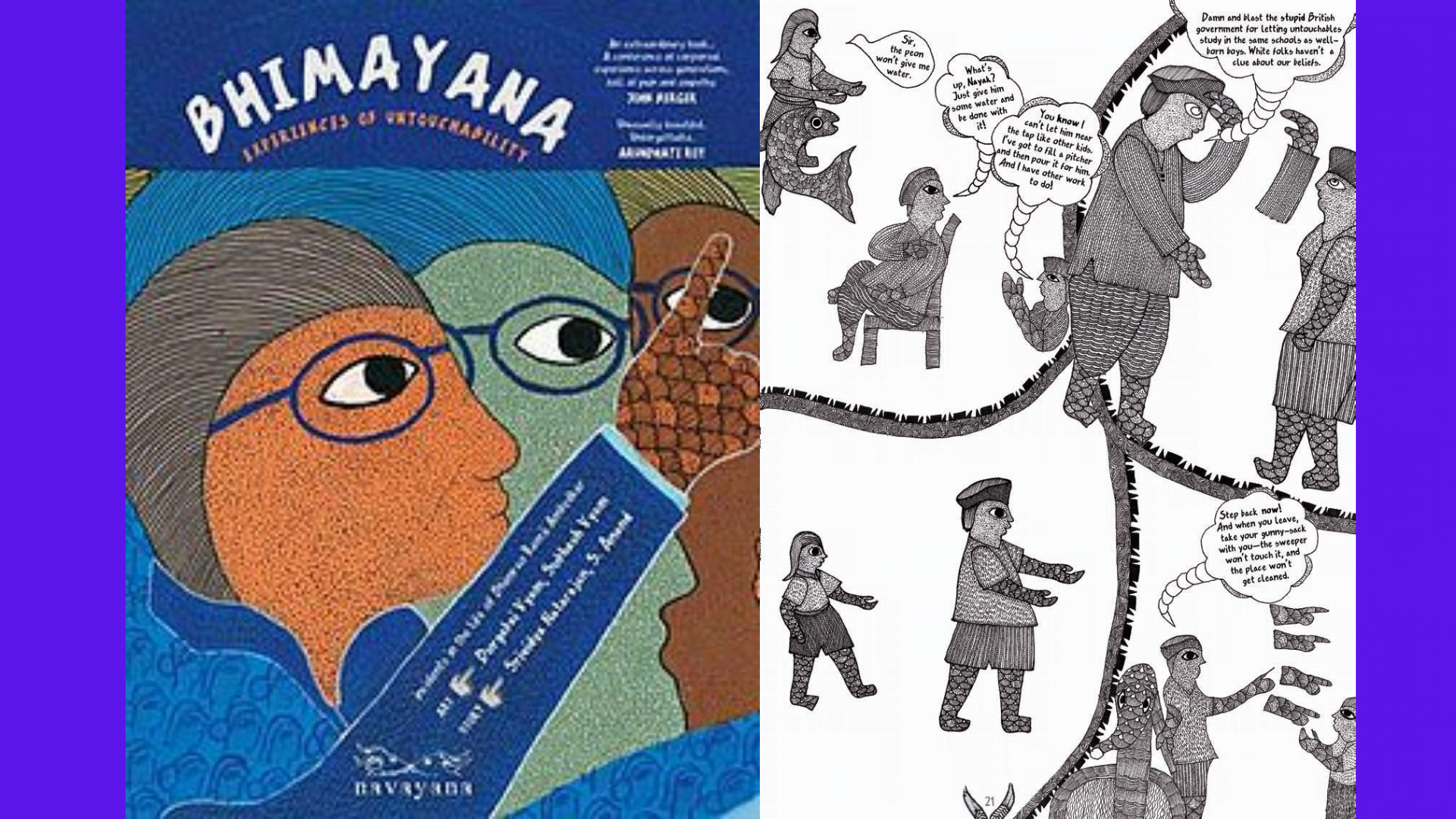

Published by Navayana in 2011, the graphic novel ‘Bhimayana: Experiences Of Untouchability’ has been included in the list of top 1001 Comics to Read Before You Die. Covering a few incidents from the life of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar; through seminal symbolisms drawn in the Pardhan Gond art style, Bhimayana makes the readers encounter the brutal realities of lives of millions of people across the country, relevant even today. Created by artists Durgabai Vyam, Subhash Vyam and writers Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand, the “catchy” medium of graphic novels serves the purpose of Bhimayana by helping it penetrate mainstream media which, as an understatement, tends to ignore caste-bias. By showing, rather than mainly telling, Bhimayana confronts people who refuse to listen.

Created by artists Durgabai Vyam, Subhash Vyam and writers Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand, the “catchy” medium of graphic novels serves the purpose of Bhimayana by helping it penetrate mainstream media which, as an understatement, tends to ignore caste-bias. By showing, rather than mainly telling, Bhimayana confronts people who refuse to listen.

Bhimayana is a hard to miss, tongue-in-cheek, forcing-you-to-draw-parallels kind of play on ‘Ramayana’. We compare the epic tale of an upper-caste Hindu male chauvinist exiled from his kingdom, kept away from royal luxuries (and dedicated a festival to); to the life a Dalit man exiled from society, “living on the edge of the village” (Pg. 14) and refused the so-called ‘social ladder’ itself in ‘Bhimayana’. Within this comparison, ‘Bhimayana’ starts with the question: Why “quotas”? And we go on to confront statements of the likes of “That’s crazy, that’s sick. The villages are stuck in a time-warp…” and how the buck doesn’t stop there.

Also read: How Reading Ambedkar Made Me Understand Feminism Better

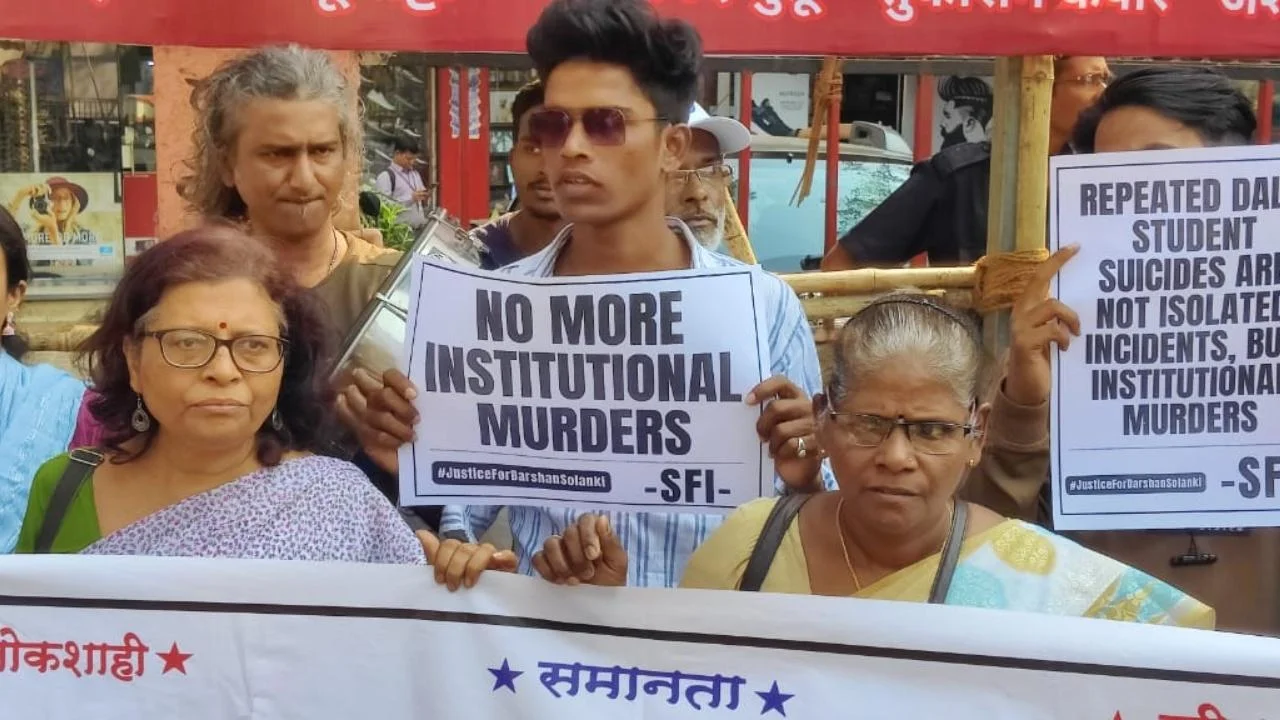

The acknowledgement that Ambedkar was not the “worst off” intends to highlight what this ‘worse’ is that we are not considering yet. If Bhim was denied the basic need of shelter, food and “as elemental a feeling as thirst” in ‘Bhimayana’ (Pg. 45), what is this “worse”? Interwoven with the narrative of ‘Bhimayana’ are multiple newspaper reports from fairly recent ‘past’ for readers in 2020 wherein there seems to lie our answer: “Yet another Dalit woman gangraped and killed in UP’s Balarampur” (October 1, 2020); “17-year-old Dalit youth not allowed to enter temple, shot dead by upper caste men for arguing” (June 9, 2020); “Indian Dalit man killed for eating in front of upper-caste men” (May 19, 2019).

If not violence, then outright denial: “Dalit student denied admission in Tamil Nadu government school” (October 30, 2020); “workers ‘denied drinking water, access to toilets for being Dalit’” (August 22, 2020); “25 Dalit Families Forced To Stay Out Of Shelter Homes During Fani In Odisha” (May 14, 2019).

The choice of using ‘tribal art’ in ‘Bhimayana’ is particularly interesting as Ambedkar’s own views on the tribal community was certainly not the most progressive; as he calls them “savages” in his ‘Annihilation of Caste’ and makes the argument that Hinduism has ‘failed’ because it couldn’t convert them into ‘good’ people. The modern politics around these two “reserved” categories is also very different. It wouldn’t be too much of a leap to guess that the creators of ‘Bhimayana’ were willing to oppose Ambedkar’s own biases. While he is an ‘icon’ in the story, he is not to be ‘put on the pedestal’.

But what particularly stands out is the sheer lack of non-male narratives in ‘Bhimayana’. While many critics have assumed that the two narrators are male and female because of their clothes, it is not made explicit within the text itself. Perhaps by not making their gender identities explicit, the creators of ‘Bhimayana’ want us to tackle our assumptions about people in certain clothes, why this social construct of clothes denoting gender even exists.

But the fact remains that critics have assumed the narrators of ‘Bhimayana’ to be either two women, or one man and one woman – still very well within the socially acceptable gender binaries. Given that patriarchy and caste are deeply interconnected, the Dalit LGBTQIA+ community and Dalit women face a deeper act of discrimination. By excluding these voices, it plays only within the old sense of normalcy that we need to move away from. At the end of the day, even though they all face the same oppressive system, caste-bias may overshadow their “feminist consciousness”. The Aunt’s presence in the story stands only in relation to the man, as the worrying ‘motherly figure’. While we do witness their “sexual, physical and psychological oppression”, similar to the aforementioned news clippings, they are always juxtaposed with Ambedkar’s own life. They do not play a “central role” in agency. While we wonder who is the protagonist in ‘Bhimayana’, we cannot for definite say it might be a non-heterosexual, non-male Dalit.

Bhimayana is a story that has not ended yet. Ambedkar’s struggles did not magically stop when he converted to Buddhism with half a million others. The readers are instead handed the baton, they must join in the struggle for basic human rights, acknowledge their social privileges and biases – of reading this story instead of having to live in it.

Also read: Dalits & Religious Conversion: Tracing The History Of The Neo-Buddhist Movement

Unlike some generic Hindi books on caste-discrimination, Bhimayana has rejected the pitiable tone. Neither is there a conclusive ending. Bhimayana is a story that has not ended yet. Ambedkar’s struggles did not magically stop when he converted to Buddhism with half a million others. The readers are instead handed the baton, they must join in the struggle for basic human rights, acknowledge their social privileges and biases – of reading this story instead of having to live in it.

About the author(s)

Anvi is a student of English literature who finds it condescending to divide literature into high and low, guiltlessly enjoys mangas, and uses her literary criticism skills to analyse them. She also likes to fight the patriarchy one at a time by hoping to spread more awareness about it.