I remember reading about the concept of private histories, quite recently. History that is documented often pertains to external events – happenings in public spaces. The wisdom, wealth of experience and private agonies that transpire within our interior lives remain undocumented other than in our memories. Since public spaces have predominantly been occupied by men, the available documented histories that we have, are also largely about male lives. The histories of women who live and operate chiefly within intimate spaces are thereby private, save a few scattered efforts. Though women are very active in the oral culture they remain in the background when it comes to documenting their thoughts.

Turkish-British writer Elif Shafak calls women “transmitters of memory” while addressing her conversations with her grandmother and mother, thereby bringing out the closed nature of the inner worlds of women. Indian author Kamala Das in her memoir about growing up in Malabar (Kerala) mentions at length about the many tips for survival, nourishment and self-care that are passed down from women to women through generations within their private interactions.

The many original thoughts and voices of women are consequentially unavailable in their original forms for the world to know other than through other women who carry them in their hearts. This is largely because women’s dialogues always have repercussions. They always feel conscious of the image that may befall them if they open up about their lives. This has held women back from being honest in documenting their lives for the longest time. Therefore, it is fair to say that the bulk of the representations that we have about the inner worlds of women are appropriated voices and imaginative constructions from the male perspective.

In fiction, this is particularly true because for the longest time, the ratio of female authors to that of male authors has been considerably low. Early women writers often adopted male pen names to put their thoughts in the public domain without judgment. The prototypes of women we have been encountering through fiction are male versions of femininity that are removed from the original. Even if they are inspired by real women, we have no documented histories of the internal lives of women to compare and contrast.

This is also perhaps why we see very few angry women in fiction, because the male imagination has seldom been besotted with angry women, if not for the possibility of taming them at some point in the narrative. This takes away the focus from the deep-rooted, socio-political triggers of female rage, depriving it of its legitimate expression and human truth. This also in turn influences the female psyche at large, creating a behavioural mould for readers to follow. It continues, cyclically.

However, with more and more female authors being published and read, there has been a significant change in the nature of the representation of female rage in fiction. Slowly and steadily, women are able to dismantle the male narrative of female fury. The initial character arcs of women created by women were also not entirely free from the patriarchal idea of suppressive angst. Women who supress their agonies and ultimately vanish from existence without making much noise like Esther Greenwood in Sylvia Plath’s Bell Jar, show us that female rage was perhaps not valid in the author’s psyche itself. Women were expected to be modest in their expressions in life as well as fiction.

The initial character arcs of women created by women were also not entirely free from the patriarchal idea of suppressive angst. Women who supress their agonies and ultimately vanish from existence without making much noise like Esther Greenwood in Sylvia Plath’s Bell Jar, show us that female rage was perhaps not valid in the author’s psyche itself.

Today, the context has changed. Our political conscience has become more accommodating of women and their original voices. Female rage is no more subtle or inconvenient. Women writing about women are raw, real and relatable. The private worlds of women are being put out for us to take stock of by female authors who understand that the anger of a woman is not to be suppressed and that, while we hail the wrath of men as transformative, heroic and even natural, women too are entitled to being open about their emotions.

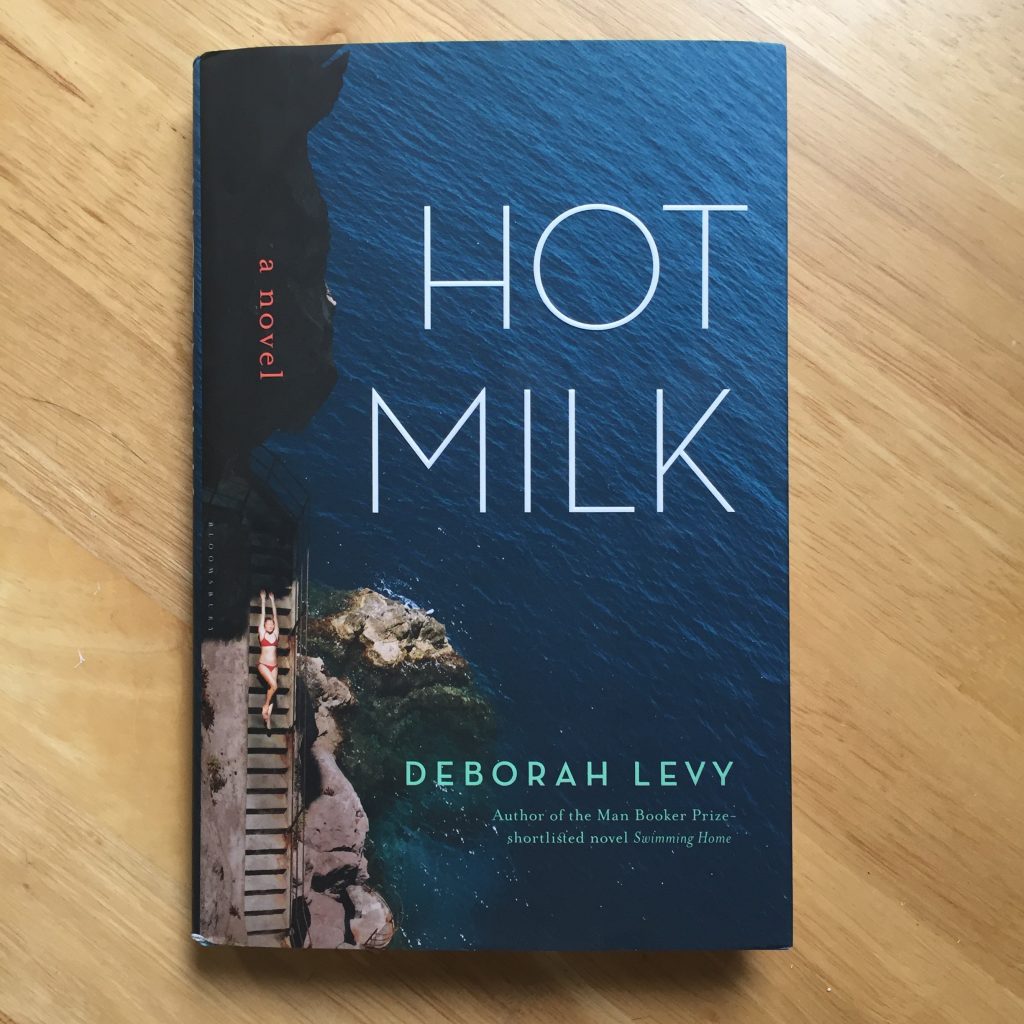

Hot Milk by Deborah Levy and Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn are two recent examples of books authored by women that present angry women protagonists who stand closer to the emotional truths of womanhood. Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2016, Hot Milk is the story of an anthropology student Sophia and her aging, paralysed, wheel-chair user mother Rose. The duo travel to a Spanish clinic seeking medical treatment for Rose’s paralysis. Gone Girl on the other hand, is the story of a woman’s seething revenge towards her failing matrimony. Both these novels subvert the popular idea of female rage. They explore the layered, cultural, gendered triggers of untapped, unexpressed female anger in eye-opening ways.

The Negation of Glory in Sacrifice

A striking, radical similarity in both these narratives is the absence of the glorification of sacrifice. It is a common practice to glorify the ability of women to take on more than they can and project it as their strength or establish it as their inherent capacity for nurture. Deborah breaks that narrative and weaves a nuanced plot about the situational necessities of women that force them to take on more than they can. The mother-daughter relationship is as dysfunctional as it comes. Rose’s disability is not explained in the book. Sophie often feels that it is Rose’s pretense to make sure Sophie is forever bound to her.

Rose on the other hand, is unwilling to acknowledge the pauses she creates in her daughter’s life and seems almost vengeful in her dependency on Sophie. Neither characters assign unnecessary piety to their relationship and are blunt about their inconveniences. The chapter where Sophie imagines leaving her mother in her wheel chair in the middle of the road, is a stark contrast to the typical, all enduring, male narrative of maternal love and its universality.

Gillian Flynn skillfully uses her protagonist Amy’s anger to critique matrimony and its structural hostility towards women. Unlike most other male narratives where the woman’s grace and integrity of character rest in her silent exit from the unfaithful man’s life, Flynn’s protagonist is chillingly human. She does not internalise her anger, or try to be the “the better, bigger person” at the cost of her sanity like most women are expected to. Her rage is rooted in the grave emotional absence of her spouse and its slow, lethal erosion of her self-esteem. It is perhaps for the first time that we are exposed to the inner workings of an emotionally abandoned woman’s escalating anger and corrosive grief. She decides to avenge herself violently.

Though Flynn does not entirely validate criminality, what she offers is an insight into the human vulnerability of a woman who is driven to her edge. While it is easy for us to accept the self-sabotaging and violence of male protagonists in similar circumstances, a woman like Amy is new and therefore perhaps difficult to digest. But that is definitely on us; our conditioning as readers and individuals who live in a world that offers men more privilege to vent and take their own emotional course on things.

Sacrifice is not presented as something inherent to women, in either of these novels, as against the bulk of literature that treat sacrifice as a woman’s ultimate destiny. Both the novels brim with the rousing frustrations of women who refuse to water down their rage for social acceptance.

Also read: Sharp Objects Review: Imperfect Women And Female Rage

Male Absence as a Trigger for Female Rage

While most other novels place a killer like Amy, Flynn’s protagonist in unilateral, villainous light, Flynn simultaneously presents her as a victim of the emotional violence of matrimony. Amy refers to herself as “easy cargo that can be jettisoned” in her marriage. Her monologue about the “cool girl” stereotype is radical, relatable and transformative. She says that men often prefer ‘cool girls’, girls who listen to them without question, admire and facilitate their illusion of grandeur about themselves, laugh at their jokes and are available for intercourse when they so desire. When Amy’s husband Nick finds a younger lover, Amy decides to go to great lengths to account for her emotional abandonment. She refuses to let Nick have it all, after escalating her insecurities with his infidelity and indifference towards her mind and body.

Flynn tells women that being who a man wants them to be in order to receive love, is carefully constructed nonsense. She brings out the grey shades of a woman’s rage, apathy and self-destruction that is deep rooted in patriarchal triggers. Amy says that once Nick is punished, she will fill her pockets with stones and jump into a river to float away like most other “inconvenient” women. This reminds us of Virginia Woolf’s death. The use of the word “inconvenient” is indicative of Flynn’s awareness about the typical male slotting into which women and their fury fall.

Deborah Levy adequately juxtaposes her plot with poetic metaphors of the sea in which Sophie swims despite the stings of the Medusas that hurt her and burn for days, to signify the lasting scars of male abandonment in women’s lives. The mother and daughter are characters who derive their frustrations from the inescapable imbalances in social, moral and political norms for women. Men, their absence and lack of emotional sensitivity as a predominant trigger for female rage is very present throughout the plot. Sophie’s complex dynamic with her father and his conspicuous absence from Rose’s life is very telling of the repercussions of male absence on women.

The prosecution of men for their lack of emotional accountability is a relevant thread that both these novels explore. Women are taught to depend on the men in their lives from early on and when they are faced with its lack thereof, it confuses them. This combined with the already existing pressure of confirming to gender roles, marriage, and social acceptability put women in a place of absolute emotional isolation and struggle for self worth. A lot of it manifests as passive aggressive outbursts of constant irritability. This is a theme that is often unique to female writing because it comes from a space of experience and is therefore strikingly original.

Both Deborah Levy and Gillian Flynn treat female rage as a natural consequence of micro aggressions, inequalities and dominant male privilege. They break the popular idea that a woman’s anger should be private and mellowed, a condition that men seldom have to follow. In their writing, female fury finds original expression. It is not on women to be graceful all the time, or to not make a scene to be respected and loved. We need more angry women in fiction, because fiction is an essential tool in making the political feel personal. Female rage is a cumulative outcome of generations of suppression and it has to be understood with a deeper sense of complexity.

Also read: Book Review: Rage Becomes Her: The Power Of Women’s Anger By…

This not only normalises the fact that women, like everyone else are entitled to raise their voices and vent their anger, but also helps to address the social, economic and gendered triggers of female rage.

About the author(s)

Sukanya is a lawyer-turned-journalist with experience in writing, editing, development communication, and advertising. She holds a graduation in law, a post-graduation in philosophy, and a post-graduate diploma in print journalism. She is also a published poet and was awarded the All India Poetry Prize in 2015. Her journalistic work is deeply focused on gender and intersectionalities, and they appear in Feminism In India, True Copy Think, and The News Minute.

Well written!