February 2020 marked the release of Kate Elizabeth Russell’s much awaited debut novel, My Dark Vanessa. The story is set in 2017 at the height of the #MeToo movement, when fresh allegations of sexual abuse against the teacher she used to have a ‘relationship’ with as a teenager, forces the protagonist, Vanessa Wye, to re-evaluate her own past. It is a powerful book, confronting issues such as grooming of minors; gaslighting; trauma and suppression; the hypersexualisation of young girls in popular culture; and institutional silence around sexual exploitation that inadvertently protects the perpetrators—problems that have spawned what people are now calling the “fourth wave” or, more accurately, the “global digital wave” of feminism.

Also read: We Need More Angry Women In Fiction: ‘Female’ Rage And Her Inner Worlds

February 2020 marked the release of Kate Elizabeth Russell’s much awaited debut novel, My Dark Vanessa. The story is set in 2017 at the height of the #MeToo movement, when fresh allegations of sexual abuse against the teacher she used to have a ‘relationship’ with as a teenager, forces the protagonist, Vanessa Wye, to re-evaluate her own past.

And yet, what immediately followed the publication of this book for Russell was not acclaim as much as questions—specifically those about the authenticity of the story itself. This was, in part, resultant of a controversy in relation to some similarities with the memoir of Wendy Orciz. However, by and large, whether at publicity tours or magazine interviews, the author was dogged with the same question: Was the story of My Dark Vanessa based on true events from her own life? With this question in the forefront, the real purpose of the book—to “spark conversation about the complexity of coercion, trauma, and victimhood”—was forgotten.

One of the issues with this is glaringly obvious—the cultural expectation that artists and writers are obliged to present details about their private life to the public; the idea that they have to be able to ‘open up’ about their trauma in order for it to be considered real. On the one hand, we do have the ethics of trauma representation to consider. However, it is almost perverse for readers to base the degree of pleasure we derive from reading fiction on whether it results from ‘real’ pain, especially when the point of these stories is to address real and concerning events that do happen all around us all the time—and that is not nearly the worst of the problem.

Underlying the treatment of Russell and many others like her is another, equally harmful and highly sexist idea, where it is assumed that serious and politically-charged works of writing by women and non-binary folks are bound to be borne of their personal experiences and are unlikely to be fruits of an active imagination and a solid grasp on worldly realities. Such attitudes unwittingly and overwhelmingly confer men with a sort of monopoly over imagination—after all, Nabokov was never asked if the predatory, pedophiliac character of Humbert Humbert in Lolita (1955) was based on his own self.

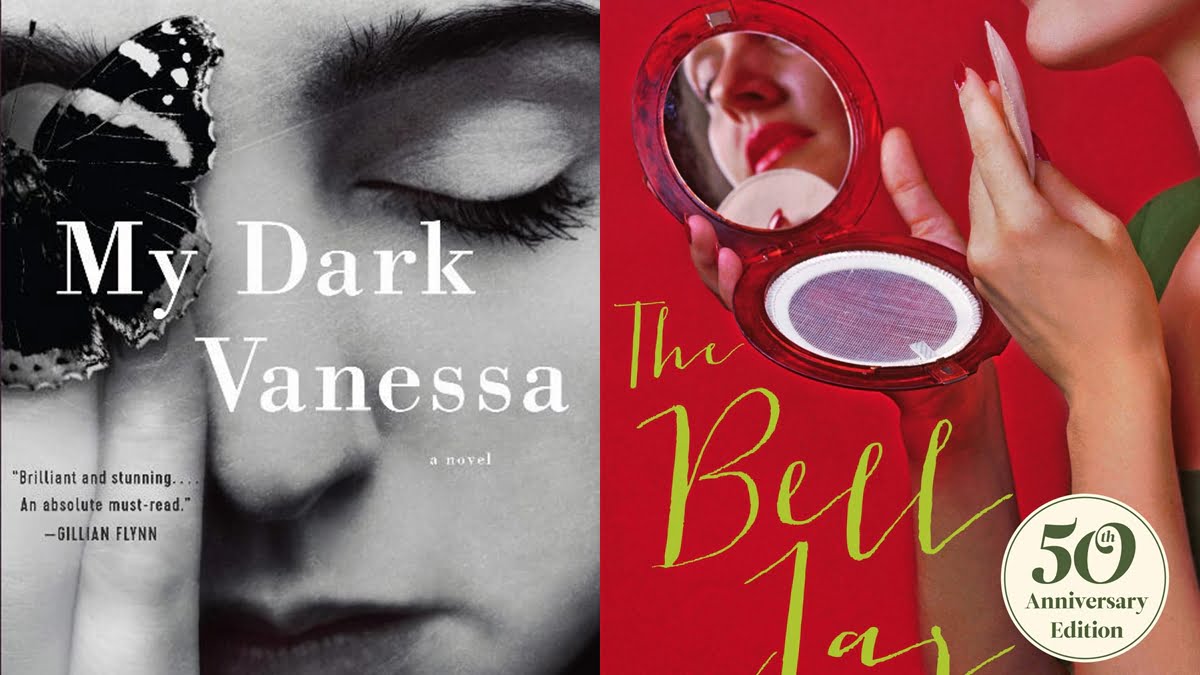

In fact, the publishers have barely allowed for My Dark Vanessa to be considered a work of serious literary and political merit, as evident from how the book has been marketed as a physical object. While the cover art is not a grave problem, it does lack originality and investment—it seems all too similar to the covers typical of the genre derogatorily known as “chick lit” at best and “those silly women’s romances” at worst, featuring a sad woman’s face alongside a ‘feminine’ motif (in this case, a butterfly). Of course, there is nothing inherently ‘inferior’ about romance novels—only, My Dark Vanessa is not a romance, and by drawing such visual parallels accompanied by an even worse worse sin in the form of an ambiguous blurb at the back, the publishers seem to consciously limit its readership, and therefore, its literary and cultural impact.

This trend of publishers depoliticising women’s writing to drive sales only within a certain demographic is not new, neither is it limited to newcomers like Kate Elizabeth Russell. Books by some of the most prominent women writers have been treated in much the same way—take, for instance, poet Sylvia Plath’s critically-acclaimed novel, The Bell Jar.

The Bell Jar has a history of particularly tasteless and sexist covers, but it is Faber’s 50th Anniversary Edition published in 2013 that draws the most ire—and for good reason. Whereas the book is a dark tale about the dehumanising treatment of mental illness in the 1950s and concerns serious topics such as suicide; electroshock therapy; and ambition within a world of contradictory (and sexist) expectations, there is no way one would be able to make the claim based on the cover, which features a stock photograph of a woman applying makeup. The impassive blurb on the back cover, too, refuses to focus on the gravity of concerns this book deals with, instead making it look like the story of a glamourous holiday followed by a footnote of an inconvenience:

“When Esther Greenwood wins an internship on a New York fashion magazine in 1953, she is elated, believing she will finally realise her dream to become a writer. But in between the cocktail parties and piles of manuscripts, Esther’s life begins to slide out of control. She finds herself spiralling into depression and eventually a suicide attempt, as she grapples with difficult relationships and a society which refuses to take women’s aspirations seriously.”

The sexism in Faber’s approach to marketing this edition of The Bell Jar is evident not only in their usage of reductive tropes and visual language, but also in noticeable absences such as that of an introductory essay. Such an absence seems almost deliberate for an edition marking the 50th year in print for a book this monumental, particularly since works by male authors of even lesser acclaim and merit obtain these much sooner. In any case, the overall effect is one of the publishers trivialising Plath’s work as something unworthy of critical study and reducing it to a crude caricature of itself rather than acknowledging it, at the very least, as a rightful equal of contemporaneous era-defining male-authored classics such as Catch-22.

Also read: 12 Powerful Books Written By Women Writers In 2020

Be it Russell or Plath; My Dark Vanessa or The Bell Jar; they invariably become testament to a disturbing trend among publishers to treat women’s writing as a genre of its own, one that needs to be marked by explicitly ‘feminine’ designs that women can recognise and men can avoid; one that reduces the issues faced by women and addressed in their writing as things concerning only women and not every single member of society and so on.

Be it Russell or Plath; My Dark Vanessa or The Bell Jar; they invariably become testament to a disturbing trend among publishers to treat women’s writing as a genre of its own, one that needs to be marked by explicitly ‘feminine’ designs that women can recognise and men can avoid; one that reduces the issues faced by women and addressed in their writing as things concerning only women and not every single member of society; one that routinely subjects women and queer authors to questions and invasiveness about their talent and ingenuity, forcing them to second-guess their position in the world even as they’re writing for a more equitable claim in it. Whereas women and feminists keep crossing old bounds and reinventing themselves, publishers are yet to get the memo and are entirely lost to the irony of it.

About the author(s)

Vartika is a journalist and writer based in New Delhi. Her work tends to oscillate between poetry and politics, and was most recently published in Speaking Tiger’s Battling for India: A Citizen’s Reader (2019).