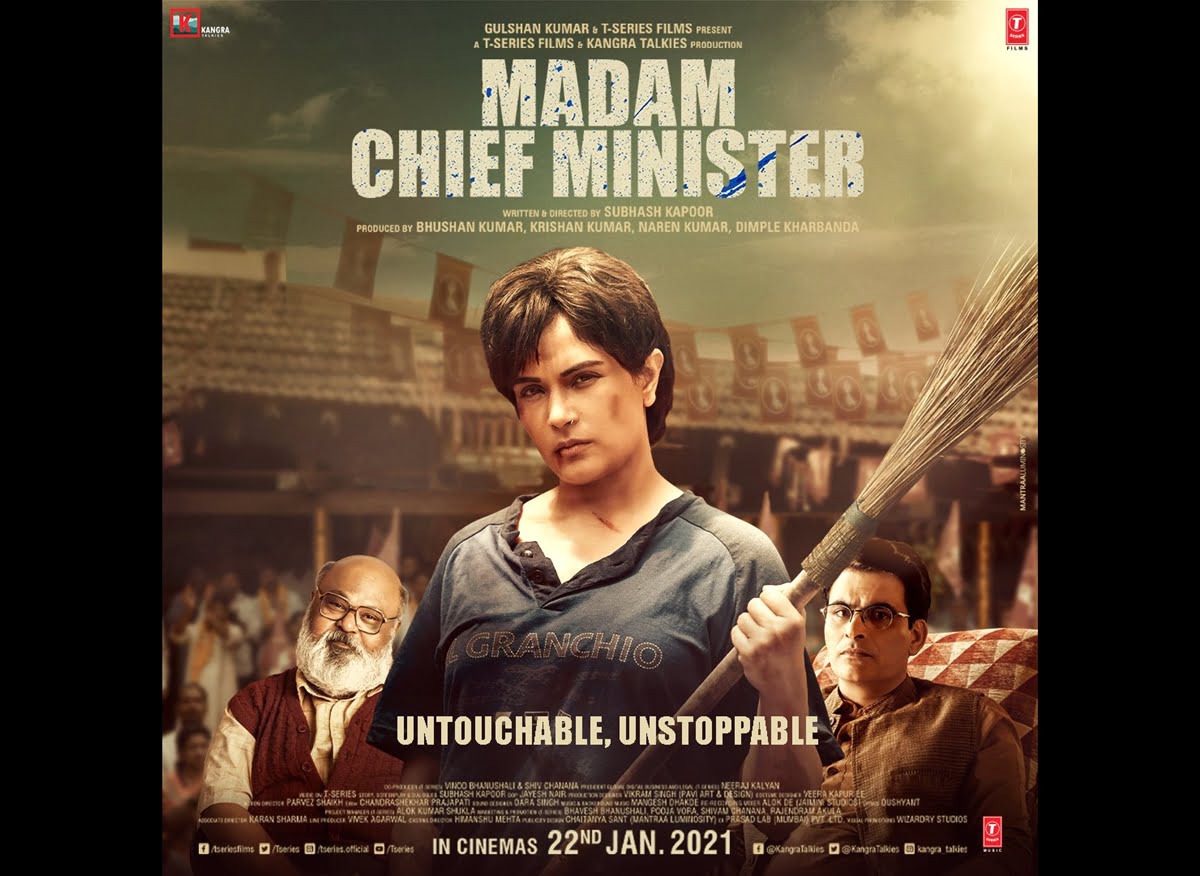

On January 4, 2021, Richa Chadha excitedly unveiled the poster of her upcoming film Madam Chief Minister, on Twitter. She wrote, “Glad to present to you all, my new movie #MadamChiefMinister, a political drama about an ‘untouchable’ who hustles and makes it big in life! Out in cinemas on 22nd January! Stay tuned!” The movie seems to be loosely based on Mayawati, who was the first Dalit woman to be appointed as Chief Minister of a state, serving four terms as the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh and who continues to be a powerful political icon and representative of the Dalit community.

The poster shows a bruised Richa Chadha holding a broom in her hand (almost like a weapon) with the tagline “Untouchable, Unstoppable.” Precisely right after, several activists and social media users took to the Internet criticising the poster for having offended the sentiments of the community. Many held that it is a tone-deaf misrepresentation of Dalits and an appropriation of Dalit narratives by upper-caste community members. In the days that followed, as a response to the feedback, Richa Chadha took what seemed a rather dismissive, defensive stance on the matter, criticising the “cancel culture” and “woke agni-pariksha” that she was being put through.

Also read: Film Review: ‘Laxmii’ Is Nightmarish, Triggering And Basically Unwatchable!

So, what exactly is wrong with the poster of Richa Chadha starrer Madam Chief Minister?

Several arguments have been put forth by allies and representatives of the Dalit-Bahujan community about why the poster of Richa Chadha’s Madam Chief Minister is problematic. If we look at Richa Chadha’s clothes, the muddy face, the broom in her hand, it doesn’t take one long to decode the savarna lens that imagines a Dalit with this aesthetic.

The broom, a symbol of savarna oppression is wielded like a weapon by the determined character portrayed by Richa Chadha who is ready to make her mark in the political world in Madam Chief Minister. Yet one ought to ask the question, why exactly is the broom important here? How is it related to her identity other than the one given to her by the brains behind this portrayal? Does her identity as a Dalit woman need to be condensed to her old, washed out clothes and the broom? Is her politics related to it? What exactly are the creators trying to say here? Simply put, did we need the broom, a symbol historically associated with the lower caste communities in the regressive varna system, in the poster at all?

“Untouchable, unstoppable” reads the tagline that, again, seems to be used as a pride-inducing slogan. This is what happens when savarnas jump to speak on behalf of the oppressed caste communities. The tagline comes across as terribly tone-deaf, given the weight of the collective trauma held by the word “untouchable”. Dalits do not wish to identify with the word “untouchable”, neither do they need their savarna saviours to use these symbols of Brahmanical oppression and mould them into something to be reclaimed. The seamless inclusion of these symbols in the poster screams ignorance and throws light on the blind spots that often cloud the savarna understanding of casteism.

Understanding the underlying belief systems behind a work of art, cinema or television is of utmost importance when it comes to representing marginalised communities. When it comes down to Bollywood, which remains to be the most influential medium of entertainment in our country, shaping our culture and society down to the grassroot level, the social responsibility lies on the shoulders of the creators and artists to do right by the people and communities they aim to represent through creative projects.

The ‘progressive’ cinematic works that aim to represent marginalised communities are not just limited to the subject or the content. Representation of Dalits does not only mean creating stories about Dalits and using their pain and suffering to make profits, but to truly represent them by passing the mic, giving them the opportunities to enrich the stories with their experiential truth, their subjective experience and most importantly, putting them at the centre of their stories. Richa Chadha’s Madam Chief Minister, a story of a Dalit woman who “hustles to make it big in life” seems to have no such connection to Dalits, with the writer-director Subhash Kapoor, producers Bhushan Kumar, Krishan Kumar, Naren Kumar and Dimple Kharbanda, and protagonist Richa Chadha coming from upper caste, upper class backgrounds with social capital and privilege.

It is important to mention here that one is not asking for too much when they wish to see a Dalit actor playing the role of a Dalit person. It is expected, and it should at least be acknowledged, if not immediately remedied. For we cannot imagine a savarna person ever understanding what it means to be Dalit, let alone portraying them with the sincerity and authenticity that is expected from such a movie. If a savarna ally really wishes to make a powerful movie representing a Dalit/Bahujan/Adivasi character, the least that needs to be done is thorough research, homework, and the much-needed inclusion of the voice of that community, be it through direct passing of the mic by casting them in appropriate roles, or by including them in secondary, but equally important roles of writers and consultants, instead of creating content such as Madam Chief Minister, Article 15, etc. that appropriates narratives and employs a savarna saviour lens, respectively.

Also read: Article 15 Review: On Why Is It A Problem To Call It Just A Problematic Film

Misrepresentation in the garb of progressive cinema may seem like a step forward, but it does more harm than good by perpetuating age-old stereotypes and fuelling the already contaminated collective conscience of the oppressor community.

Featured Image Source: Twitter

About the author(s)

Priyanka is an unfulfilled engineer and an MBA graduate from IIM Indore. She is a writer, interested in carving the world through her biased lens, painting pictures with heavy imagery and highlighting the mundane, often ignored, but essential aspects of life. Her latest project is The Mental Indian, an attempt to de-stigmatize mental health in India, through stories, perspectives and conversations.