Forest Range Officer (RFO) Deepali Chavan, who was also lovingly known as ‘Lady Singham‘, died by suicide at her residential headquarters on Thursday, March 25. Deepali was working in the Harisal village of the Melghat forest division, in the Amravati district of Maharashtra. She left a letter to M S Reddy, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forest (APCCF) and Field Director of Melghat Tiger Project, accusing Vinod Shivkumar, Deputy Conservator of Forest (DyCF) of Gugamal Wildlife Department and her supervisor, of sexual harassment, mental torture and as the responsible person for her death. She also wrote a letter to her husband along with Reddy, mentioning Shivkumar as the only person responsible for her death.

Shivkumar was arrested and suspended from duty soon after Deepali’s death and Reddy was suspended on April 1. Yet, Deepali’s death is a microcosm of the manifestations of sexual, mental, and institutional harassment still prevalent in our society. Deepali’s case is the latest that raises questions on the social and systemic inability to get the laws against sexual harassment for women at the workplace, implemented, especially in professions which are male-centric and male-dominated, with no consideration for the women who have taken up the profession.

Also read: Sexual Harassment In The Workplace Is As Much About Power As It Is About Gender

Deepali’s case is the latest that raises questions on the social and systemic inability to get the laws against sexual harassment for women at the workplace, implemented, especially in professions which are male-centric and male-dominated, with no consideration for the women who have taken up the profession.

In 1992, four upper-caste men from Rajasthan raped Bhanvwari Devi, in front of her husband, for working to stop child marriage. The case resulted in the making of the Vishakha guidelines for the protection, solution, and redressal for female employees at the workplace. Ironically, a lower court acquitted the accused in Bhanwari Devi’s case after a lesser punishment of nine months in jail. Even after 29 years, Bhanwari Devi is still waiting for justice. The Indian Government enacted the Sexual Harassment (Prevention, Prohibition, Redressal) of Women at Workplace in 2013 (POSH Act) to protect workers from sexual harassment in both private and public sectors. The POSH Act mandates that every organisation with ten and more employees must have an Internal Complaint Committee (ICC) within, in addition to a Local Committee (LC) headed by the district officer in the district to prevent, address the issue(s) of sexual harassment, and to create a safer environment for women at work. It is important however, to check if the act really protects women at all workplaces.

The National Bar Association, in its survey of over 6,000 employees—the largest conducted in India so far—found that sexual harassment is prevalent in all job sectors, ranging from making sexual comments to directly asking sexual favors. It also found that most women chose not to file the complaints because of stigma, fear of retribution, lack of awareness about the laws, or lack of confidence in the mechanism and the consequential embarrassment. A nursing officer in Delhi said she could not get justice after filing a complaint with the ICC because her perpetrator was the senior supervisor and the ICC could not do much other than threatening her to take back the complaint. After the ICC denied taking the proceedings further she moved to the district-level local committee. After a year, she was informed that the committee had already filed a final report quoting the police officials saying she did not have enough evidence to prove the case. The case closed there.

A couple of years ago, this lax implementation of the POSH account in India when it comes to holding the mighty men in powerful positions accountable, was made evident in the sexual harassment case against Ranjan Gogoi, former Chief Justice of India and current Rajya Sabha MP. After the case was filed against him, Gogoi himself convened a Supreme Court special bench and headed it with other two male members to address the issue without involving Indu Malhotra, the chairperson of the Internal Complaint Committee of the Supreme Court. While doing so he broke the principle of natural justice that denies a person to be a judge of his case. Neither did he follow the POSH guidelines that mandate the committee to be headed by a woman and comprise a majority of women. After further investigation, Ranjan Gogoi was given a clean chit and the woman opted out of the Supreme Court probe saying the atmosphere of enquiry was frightening.

Also read: ‘You Don’t Behave Like A Muslim’: Being Muslim At The Workplace And Facing Islamophobia

In Deepali’s case, she headed the ICC herself, along with two other women forest guards. Despite heading the ICC and complaining to Reddy—the forest director several times, she could not take any action against the accused Shivkumar since the former firmly stood behind him, Deepali alleged in the letter. After such incidents, there remains very little to less credibility with the ‘internal mechanisms’ formed for timely redressal as well as with the judiciary, the guarantor of justice. Further, Deepali’s case is also significant in how this impedes many women from taking up employment in forest departments, thus discriminating against and restricting women’s mobility.

Women in forest departmentsreported that they’d prefer desk jobs than being on the field, which forces them to leave home for long spells. They are, thus institutionally forced, to work in the administration because of their responsibilities towards their families and children, in addition to the fear of being sexually assaulted while on field work in the forests.

Women in forest departments reported that they’d prefer desk jobs than being on the field, which forces them to leave home for long spells. They are, thus institutionally forced, to work in the administration because of their responsibilities towards their families and children, in addition to the fear of being sexually assaulted while on field work in the forests.

Being a FRO, Deepali chose to do regular field visits, as a result of which she would have to stay away from her husband who worked in Chikhaldara. She mentioned in her letter how Shivkumar would not allow her to visit her husband and family during breaks, and gave physically tiring tasks even when she was pregnant. The pressure was so much that she had no option but to choose between her work and her family, and could not have both. The rigid bureaucratic structures and patriarchal attitudes do not take women seriously, create more gender-positive mechanisms to ensure women can manage a work-life balance and instead, restrict their movements after sexual harassment, rather than convicting the perpetrator. These structures continue to function under the assumption that “women can’t have it all”, thus creating impediments for women who aspire to work on field and raise a family at the same time.

There are several women undergoing the same or even worse situations in the unorganised sector too. The unorganised sector has a significant amount of women from socially and economically underprivileged backgrounds who are the primary earners of their families and have no choice in the kind of work they want to do. They work merely for their survival and gulp this down the throat quietly to preserve their jobs.

To not make women suffer in silence or lose their jobs because of sexual harassment at the workplace, the evaluation of the implementation of the POSH is alarmingly needed along with creating an inclusive and flexible bureaucratic structure that encourage women to work in the male-dominated spaces. There is also need to develop a perspective that takes sexual harassment seriously before more cases get shut and more lives get lost.

Dnyaneshwari Burghate is pursuing her master’s in Women’s Studies from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. Introverted yet observant and analytical, she loves to absorb whatever goes on in the world around her and weave lucid tales out of it. She firmly believes in the power of the pen and feminism. She can be found on Instagram.

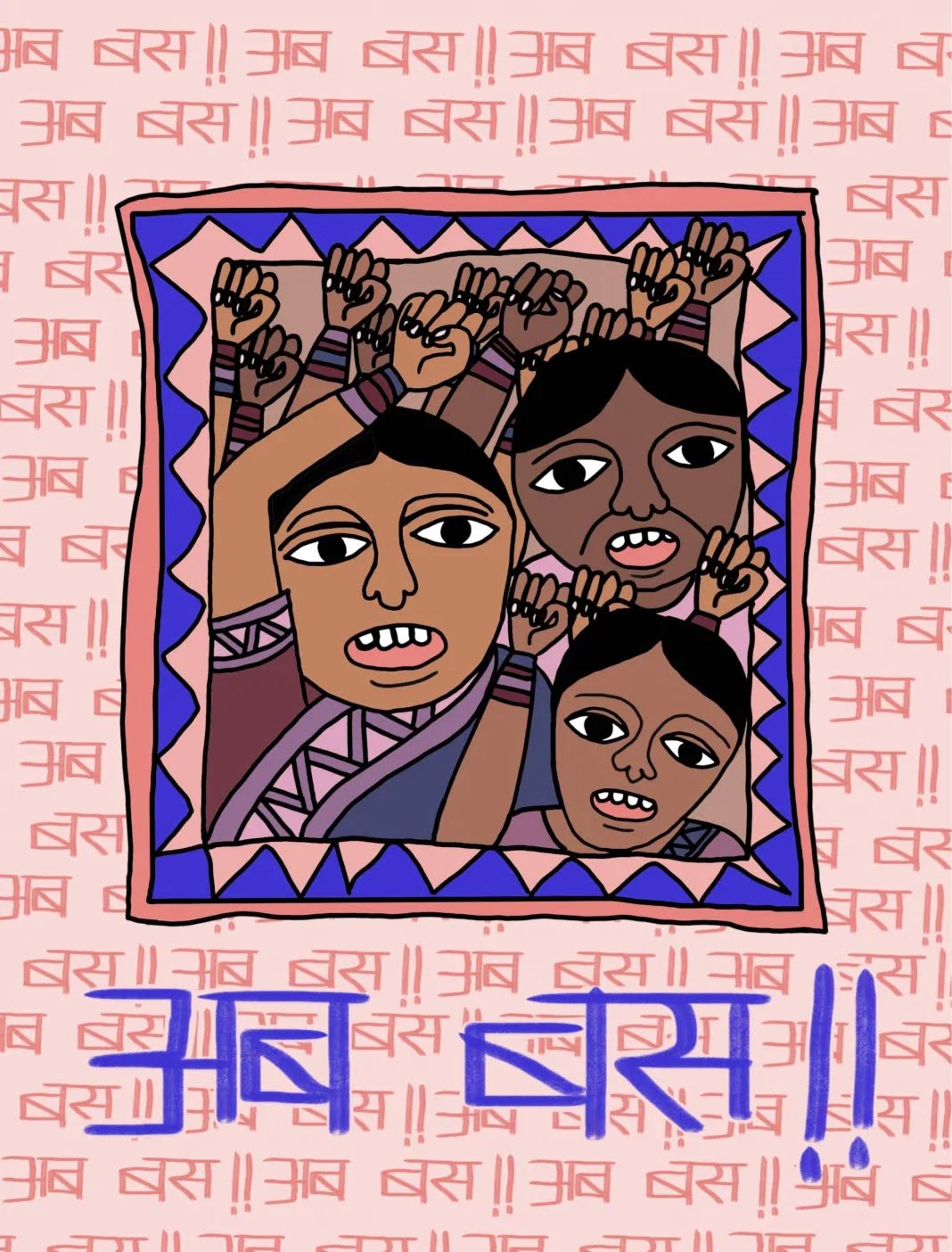

Featured Image Credit: Sunidhi Kothari/Feminism In India

Very well written, it is factual